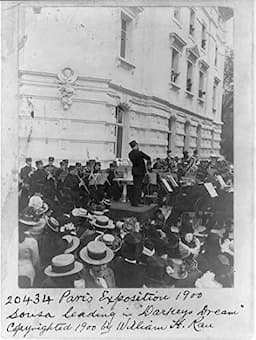

Sousa in Paris

During July 1900, as part of an extended European tour, John Philip Sousa and his band performed at the opening of the Universal Exposition in Paris. Celebrating the 4th of July, they played at the dedication of the American Pavilion and subsequently paraded through the principle streets of Paris. The band offered plentiful Americana to Parisian ears. Not only Sousa’s own marches such as “Hail to the Spirit of Liberty,” but also performances of such tantalizing titles as “On the Plantation,” “Custer’s Last Charge,” “Songs of the Cotton Pickers,” and even “Darkeys Dream”.

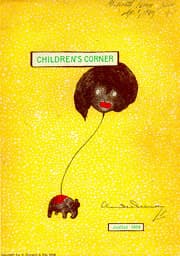

Debussy: Children’s Corner

Above all, Sousa’s performances inspired a veritable Parisian Cakewalk Craze, a pre-ragtime dance form popular until about 1904. Cakewalk routines quickly transferred into a theatrical dance and featured at the famous aquatic stage of the new circus, the Casino de Paris, and the cabarets of Montmartre in Paris. It was in this field of social and cultural minstrelsy that Claude Debussy entered the syncopated Americanism with “Golliwogg’s Cake-Walk” from the Children’s Corner (1908). This was followed by The Little Nigar (1909), a theme he reused in La boîte à joujoux (1913); “Minstrels” from the first book of Préludes (1910), and “General Lavine”-Eccentric from the second book (1910-1913). In his first two compositions Debussy seemingly relied on “authentic black subjects,” while the latter two shift to “their white imitators.”

Claude Debussy: Préludes, Book 2 “Général Lavine – Eccentric” (Vincent Larderet, piano)

Set and costume of Parade by Pablo Picasso

There is much scholarly debate whether the Parisian craze represents “white appropriative desires that fashioned an imagined ‘otherness,’ a reified racial presence considered primarily as primitive and grotesque.” Or alternately, if the popularity of the cakewalk and subsequent ragtime “emerges from a wide array of French cultural practices at the time, including American chic, athleticism, the other-worldly and the clown, and was thus more culturally ambivalent and socially in flux than presented in the literature.” I suspect that it really isn’t an either or, but rather a combination of both arguments. There can be now doubt, as the publisher Leo Feist proclaimed that, “Paris has gone ragtime crazy,” and that a circus-like atmosphere permeated the city.

Set and costume of Parade by

Pablo Picasso

In his scenario entitled Parade, Jean Cocteau came up with a snapshot of Parisian society intended to antagonize and offend almost everybody. The scenario features a Chinese magician, and a little American girl and acrobats parade outside their tents giving free excerpts from their full performance in an effort to lure the audience into buying tickets. The crowd, however, mistakes their samples for the main show and disappears. As you know, Cocteau assembled the greatest artistic minds offered by Paris at that time, and the “enfant terrible” of the Parisian music scene Erik Satie composed the music. The “Little American girl,” unsurprisingly dances a lugubrious ragtime mirroring the craze for American popular music. Cocteau’s notion of American womanhood, which was inspired by Hollywood heroines like Mary Pickford and Pearl White, involved a high degree of athleticism, and unselfconscious sex appeal. “She swims, boxes, dances, and leaps onto moving trains,” Cocteau writes, “all without knowing that she is beautiful.” Maria Chabelska, who interpreted Satie’s ragtime music with great charm and gusto brought the dance to a poignant conclusion when, thinking herself a child at the seaside, she ended up playing in the sand.

Erik Satie: Parade, “Rag-Time” (Klára Körmendi, piano)

George Antheil

The American pianist and composer George Antheil wrote in 1927, “I am the only American born composer, … who has ever approached even a sensation in any country outside of his own. I don’t say I am the last but only the first. This is a distinct step forward, a thing which my countrymen have not given me enough credit for.” Born in Trenton, New Jersey, he studied piano with a Liszt student in Philadelphia before moving to New York to study with Ernest Bloch. Antheil came to Europe in the 1920s and performed in Berlin, London, Vienna and Budapest. He subsequently moved to Paris, where he was to become one of the most enigmatic and sensational members of the artistic community. He quickly struck up lasting friendships with various member of the Parisian arts scene, including Picasso, Joyce, Man Ray, Satie, Cocteau, Dalí and Hemingway. In 1926 Antheil premiered the “Ballet mécanique,” a work originally written as a film score and using a player piano, eight grand pianos, four xylophones, two electric bells, two aircraft engines, tam tam, four drums and sirens. “I want to make music hard as stone” he writes, “and start with its fundamental principles, where it is archaic and indestructible.” Using collage techniques, the essence of ragtime reverberates throughout the opening movement of his Airplane Sonata.

George Antheil: Airplane Sonata, “As fast as possible” (Gottlieb Wallisch, piano)

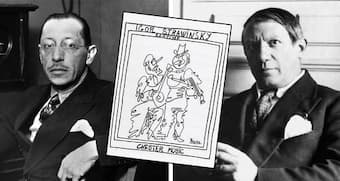

The first collaboration between Picasso and Stravinsky — ‘Ragtime’

With George Antheil bringing the ragtime within the context of “machine music,” Igor Stravinsky was guided by a somewhat different aesthetic. When Ernest Ansermet returned to Paris from the Russian Ballet’s second American tour in 1918, he presented Stravinsky with a bundle of ragtime music in the form of piano reductions and instrumental parts, which the composer copied out in score.

Portrait of Stravinsky by Picasso

Stravinsky remembered in 1961, “With these pieces before me, I composed the “Ragtime” in Histoire du soldat, and after completing Histoire, the Ragtime for eleven instruments.” Stravinsky subsequently reduced the latter Ragtime for piano in 1919, and publically performed the piece. Stravinsky places his “Ragtime” within the distortions and grotesquery of the Cubist movement spearheaded by Picasso. He deconstructs the ragtime, breaking it up into jagged fragments and shards, and subsequently reassembles them in a highly distorted fashion. Incorporating ostinato, shifting accents, and bitonality, the irregular meters give the piece an entirely improvisatory character.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Piano Rag Music (Anatoly Sheleudyakov, piano)

Loved the article on Paris Does the Ragtime. Thank you.