“Music is a splendid lawless land where no one can give orders”

Slobozhan kobzar P. Drevchenko and Poltava kobzar M. Kravchenko in Kharkiv 1902

The Ukrainian region suffered considerable political instability and oppression during the early 20th century. In fact, Ukrainians entered World War I on the side of both the Central Powers, under Austria, and the Triple Entente, under Russia. “Three-and-a-half million Ukrainians fought with the Imperial Russian Army,” while 250,000 fought for the Austro-Hungarian Army.” With World War I destroying both Empires, the Russian Revolution of 1917 plunged the entire region into a long and bitterly fought war of independence.

Taras Shevchenko

Several Ukrainian states briefly emerged, and the internationally recognized Ukrainian People’s Republic was declared on 23 June 1917. Ukraine sided with Poland against the Bolsheviks, but in the end, Ukraine became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in December 1922. Political instabilities and ever-changing national borders aside, the definition of Ukrainian identity already emerged in the mid-19th century in the writings of the poet, folklorist, and ethnographer Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861). Considered the founder of modern Ukrainian literature, Shevchenko wrote poems in the Ukrainian language that openly ridiculed members of the Russian Imperial House. In 1847 he was politically convicted, arrested, and exiled for explicitly promoting the independence of Ukraine.

Mykola Lysenko: “Dumka-Shumka,” Rhapsody on Ukrainian Folk Themes

A prophetic figure in the Ukrainian Enlightenment, Shevchenko wrote 237 poems, but only a handful was published during his lifetime. In his “Testament” of 1845 he gave voice to his connection to land, people and country, and to the spirit of resistance.

When I die, then make my grave

High on an ancient mound,

In my own beloved Ukraine,

In steppeland without bound:

Whence one may see wide-skirted wheatland,

Dnipro’s steep-cliffed shore,

There whence one may hear the blustering

River wildly roar.

Till from Ukraine to the blue sea

It bears in fierce endeavor

The blood of foemen — then I’ll leave

Wheatland and hills forever:

Leave all behind, soar up until

Before the throne of God

I’ll make my prayer. For till that hour

I shall know naught of God.

Make my grave there — and arise,

Sundering your chains,

Bless your freedom with the blood

Of foemen’s evil veins!

Then in that great family,

A family new and free,

Do not forget, with good intent

Speak quietly of me.

Boris Lyatoshinsky: Ukrainian Quintet, Op. 42 (Bogdana Pivnenko, violin; Taras Yaropud, violin; Kateryna Suprun, viola; Yurii Pogoretskyi, cello; Iryna Starodub, piano)

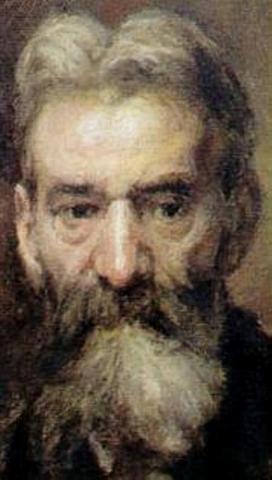

Borys Mikolayovich Lyatoshynsky

Occupiers of Ukrainian lands have always successfully banned or suppressed large-scale musical expression, such as opera and symphonic music. However, as commentators have noted, “they have not been able to crack down on the more intimate musical forms. As such, choral singing and chamber music are the most authentic examples of Ukrainian music. In a previous episode we looked at the accomplishments of Mykola Lysenko (1842-1912), widely considered the “Father of Ukrainian music.” In today’s episode we explore some Ukrainian chamber music directly or indirectly inspired by Shevchenko and Lysenko. For his Shevchenko Suite, Borys Mikolayovich Lyatoshynsky (1895–1968) reflects the mood of the poet’s brief epigraph:

As the sun sets and hills grow dark,

as the birdsong ends and fields fall silent,

as the people laugh and take their rest,

I watch… My heart hurries

to the twilit gardens of Ukraine.

Borys Lyatoshynsky

His expansively and highly emotionally Ukrainian Quintet was composed in 1942 and combines Ukrainian folk melodies with contemporary harmonic and formal traits. Lyatoshynsky hailed from the city of Zhytomyr, and moved to Kyiv in 1913. He enrolled in Kyiv University to study law, but then transferred to the recently founded Kyiv Conservatory where he studied with Reinhold Glière. Lyatoshynsky embarked on an academic career, teaching at Kyiv and the Moscow Conservatory. He composed in a variety of genres, and counted Schumann, Borodin and Scriabin among his greatest influences.

Valentin Silvestrov: String Quartet No. 1 (Rosamunde Quartet)

Valentin Silvestrov

Up until the end of the 1920s, Ukraine enjoyed a certain degree of cultural freedom. All that changed when Joseph Stalin took control of the USSR. The unprecedented suffering inflicted by the ruthless state-sponsored bureaucracy of Stalinist Russia had a devastating effect on Ukrainian society. In particular, artists and performers frequently found themselves under the microscope of an all-embracing and uncompromising state machinery, which demanded the adaptations of classical models in pursuit of socialist realism. In music, this meant a monumental approach, and an exalted rhetoric based on optimism. And Ukraine’s most valuable achievements and accomplishments were appropriated by the Soviet State.

Valentin Silvestrov

It took a younger generation of Ukrainian composers in the mid-1950s, “nearly all of them pupils of Lyatoshynsky, to pursue a more radical direction with assistance from their mentor.” Among them is Valentin Silvestrov (born in 1937), who was initially a self-taught musician. A civil engineer, Silvestrov took evening courses in music and later studied composition and counterpoint with Lyatoshynsky and Levko Revutsky at Kyiv Conservatory. Silvestrov was never interested in an academic career, and he made his living as a freelance composer based in Kyiv. “Considered one of the leaders of the Kyiv avant-garde,” he was strongly censured by Soviet leadership and his music was essentially unheard in his native city. While premieres of his music played to great acclaim abroad, his artistic expressions fell victim to the systematic purges and censorship employed by the Soviet regime.

Reinhold Gliére: String Quartet, Op. 2 (Pulzus String Quartet)

Reinhold Gliére

As the teacher of Sergei Prokofiev, Aram Khachaturian and Alexander Mossolov, Reinhold Moritzevich Gliére (1875-1956) is officially considered the heir of the Russian Romantic musical tradition. His invariably nationalistic Russian Romanticism in music found favor with the political establishment, and Stalin and his cultural ministers appointed him chairman of the organizing committee of the Soviet Composer’s Union. His compositions, including three symphonies, four string quartets, two complete operas, two ballets, a number of concertos, and hundreds of songs, piano works, and chamber pieces, were deemed suitable for Soviet consumption, and he was even sent to Azerbaidzhan in 1923 to assist “Soviet Development.” Political considerations informed his opera The Worker of Baku, and in his musical celebration of the realization of Stalin’s plans for a canal in Uzbekistan and the Heroic March for the Burylat-Mongolian ASSR. However, Gliére was actually born in Kiev, son of successful instrument maker from Saxony and his Polish wife. He studied violin at an early age and produced his first tentative efforts in composition at the age of fifteen. Given his enormous musical talent, it was decided that Reinhold should continue his studies at the Moscow conservatory, and he graduated in 1900 with the highest award. His graduation piece is a string quartet firmly rooted in the folk-inspired tradition of Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov. Although some critics suggest that Gliére’s music and his “Ukrainian roots are deeply contaminated by the Russian-oriented folklore complex,” the work, nevertheless, possesses an appealing and charming naïveté.

Viktor Kosenko: 2 Pieces, Op. 4 (Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin; Angelina Gadeliya, piano)

Viktor Kosenko

Prior to the Soviet occupation in 1919, a good many composers pursued their studies in Vienna, Prague or Leipzig, and some sought careers via studies in Moscow. Although Viktor Kosenko (1896-1938) was born in Saint Petersburg, his family moved to Warsaw only two years after his birth. He displayed great musical talents at an early age, and it is said that at the age of nine, “he was able to play Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata from memory, as he heard his older sister Maria practicing this piece.” He began his formal musical training in 1905, but had to leave Warsaw for Saint Petersburg with the beginning of World War I. After graduating from the Conservatory in 1918, Kosenko joined his family in Zhytomyr, at that time the cultural center of the Volyn province. Eventually, Kosenko became director of the Zhytomyr Music School and perfected his compositional style. He composed a large number of piano pieces, chamber compositions, and countless works for children and for plays. “He was also heavily involved in a myriad of musical activities such as the creation of a music society, concert appearances, the organization of his piano chamber trio, vocal quartets and even a symphony orchestra, besides serving as accompanist player for different ensembles in the musical life of the city.” As was rather all too common during these tumultuous times, Kosenko fell into deep conflict with the new Stalinist regime and he was forced to move to Kyiv. Kosenko died at the age of 42, and only grudgingly did Soviet authorities recognize his efforts on behalf of popularizing Ukrainian nationalist music. He was personally awarded the “Order of the Red Banner” by the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Nikita Krushchev.

Nicolai Kapustin: Piano Quintet, Op. 89 (Alexander Chernov, violin; Vladimir Spektor, violin; Svetlana Stepchenko, viola; Alexander Zagorinsky, cello; Nicolai Kapustin, piano)

Nikolai Kapustin © Peter Andersen

History books clearly tell us that Nikolai Kapustin (1937-2020) was a Soviet and Russian composer and pianist. However, Kapustin was born on 22 November 1937 in the small town of Horlivka, situated in the Donetsk province of Eastern Ukraine. He initially took piano lessons from the violinist Ivanovich Vinnichenko, who realized the child’s huge potential as a pianist. However, it was Lubov Frantsuzova, a graduate from the St Petersburg Conservatory, who prepared Kapustin for the entrance exam to the Moscow Conservatory. Kapustin was immediately accepted into the preparatory class of Avrelian Grigoryevich Rubakh, a student of Felix Blumenfeld, who had also taught Vladimir Horowitz and Simon Barere. The “Post-Stalin Thaw” accorded greater freedom to many aspects of Russian life, and Jazz became a symbol of freedom. Kapustin remembered, “in the 50s it was completely prohibited, and there were articles in our magazines that said it was typical capitalistic culture, so we had to throw it away.” For Kapustin, this greater musical freedom led to a convincing and idiomatic fusion between the language of jazz and the structural demands of classical music. Skillfully blending and transcending both musical traditions, his compositions present a unique amalgamation of the virtuosity of classical pianism and the improvisational nature of jazz. Composers, according to Kapustin “can greatly profit from this musical confrontation. One side can learn a great deal from the rhythmic vitality and swing of jazz, while jazz musicians can find new avenues of development in the large-scale forms and complex tonal systems of classical music.”

Myroslav Skoryk: Carpathian Rhapsody (Natalya Pasichnyk, piano; Emil Jonason, clarinet)

Myroslav Skoryk

Myroslav Skoryk, born in Kviv on 13 July 1938 is probably best remembered for composing the musical score to the 1964 Ukrainian film “Forgotten Ancestors,” directed by Serge Paradjanov. Prior to the 1960s, Moscow had “crippled the culture’s ability to communicate directly with the rest of the world by bestowing or withholding its approval.” However, the generation of the 1960s in Ukraine produced two distinct styles.

Firstly, music “of a highly abstract nature grew out of the experience with the European avant-garde, known as the Kyiv avant-garde.” A second stream developed that has been described as the “new folklorism, the precursor of a movement that reached its full development in the 1980s.” Scholars have declared Myroslav Skoryk the “undeclared leader of this form of musical expression in Ukraine. His music, specifically from the mid-1960s through the mid-1980s is “wedded to folkore, as Skoryk fully realized his style of building a work from a short melisma, derived by synthesizing idiomatic folk rhythms and melodic gestures.” Skoryk was awarded the titles of Peoples’ Artist of Ukraine and Hero of Ukraine, and he received the Shevchenko National Prize for his Cello Concerto.

Victoria Polevá

Victoria Polevá was born in Kyiv on 11 September 1962 into a family of musicians. Her grandfather was a renowned singer, and her father a respected composer. She studied composition in the studio of Ivan Karabyts (1984-1989), and Levko Kolodub (1990-1995) at Kyiv Conservatory, where she also taught composition in 1990-2005. Polevá composes in a wide range of genres, and “her music delivers the opportunity for the listener to submerge into the depths of spiritual exploration of people coming from different backgrounds and religious confessions.” The composer describes herself as an “explorer of the world” and emphasizes the complexity of personal self-understanding paraphrasing the above-mentioned description into “the world in exploration of me.” She explains the ease of the creative process as follows: “The music itself creates me. I write unintentionally. I read, I suffer, I love, I write. I am the reflection of music.” Her works are regularly performed on the most prestigious stages around the world, and her more recent compositions “are drawn from spiritual themes and musical simplicity… a style since identified as “sacred minimalism.” The Simurgh Quintet dates from the year 2000, and it was inspired by a Sufi poem titled “The Conference of the Birds.” Featuring the interaction of psalmodic speech in the piano and choral singing in the strings, “the musical material of the quintet has a hidden inner text and comes from the Orthodox practice of prayer.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Victoria Poleva: Simurgh-Quintet