Warning: Opinions Ahead, Proceed with Care!

Music is often hailed as a universal language, capable of transcending borders and expressing emotions that words alone often fail to capture. However, within its vast repertoire lies a sharper edge: the tradition of musical invective.

It is a form of artistic expression in which composers, songwriters or critics use music, lyrics, or written critique as a vehicle for sharp-witted criticism, satire, or outright insult. It targets rivals, societal ills, or specific works with a blend of creativity and venom.

Claude Debussy: Images, “Rondes de printemps”

Musical Invective

Nicolas Slonimsky: Lexicon of Musical Invective

Music critics have long played their own role, wielding pens like swords to demolish works and composers with a ferocity that rivals any lyrical jab. Musical invective is as old as the art form itself, and composers never hesitated to skewer their peers and critics, often turning reviews into public execution.

Far from being mere gossip, musical invectives carry weight beyond personal vendettas. They serve as satire, rebellion, or cultural commentary, amplifying grievances through rhythm and prose. A composer might pen a mocking melody to settle a score, while a critic’s venomous column could bury a work under the rubble of its own ambition.

Some years ago, Nicolas Slonimsky published a “Lexicon of Musical Invective,” a book that compiled critical assaults on composers. It reminds us that music history is not just a parade of triumphs but a gallery of grudges, where notes, lyrics, and scathing words draw blood in equal measure. To get this series started, let’s take a look at dissonance aimed at Claude Debussy.

Claude Debussy: Première rapsodie for Clarinet and Piano

Personal Attacks

Claude Debussy, 1905

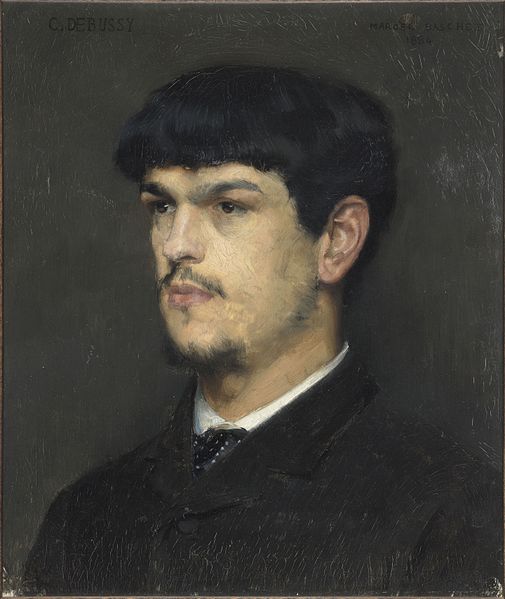

While Claude Debussy is celebrated today as a pioneering figure in modern music, his innovative style drew sharp criticism during his lifetime. Musical invectives against Debussy came from composers, critics, and contemporaries who found his work perplexing, chaotic, or even offensive.

No newspaper today would publish a piece of music criticism in which the composer is called an idiot or madman. Nowadays it’s even difficult to call music ugly, but once upon a time, physical descriptions of composers as a way of defaming them was rather common.

James Huneker provided an extraordinary description of the physical appearance of Debussy. He wrote in the New York Sun on 19 July 1903. “I met Debussy the other night and was struck by the unique ugliness of the man. His face is flat, the top of his head is flat, his eyes are prominent, the expression veiled and sombre, and altogether, with his long hair, unkempt beard, uncouth clothing and soft hat, he looked more like a Bohemian, a Croat, a Hun, than a Gaul.

I see his curious asymmetrical face, the pointed fawn ears, the projecting cheek bones—the man is a wraith from the East, his music was heard long ago in the hill temples of Borneo; was made as a symphony to welcome the head hunters with their ghastly spoils of war!”

Claude Debussy: Estampes, “Pagodes” (arr. Percy Grainger)

Pelléas

Claude Debussy’s Pelléas

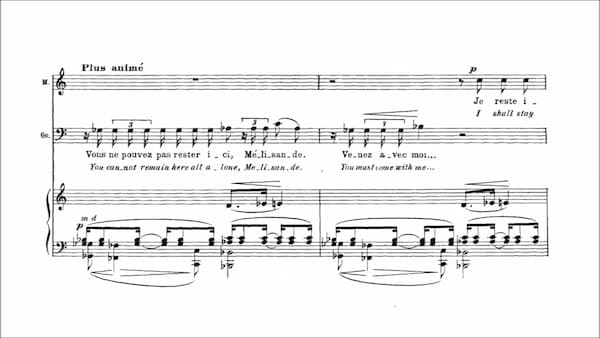

Claude Debussy premiered his revolutionary opera Pelléas et Mélisande in 1902. While celebrated for its innovative harmonic language, atmospheric orchestration, and departure from traditional operatic forms, it has also faced criticism for its perceived lack of dramatic momentum and emotional clarity.

Detractors, including some early reviewers and composers like Puccini, argued that its “subtle, symbolist narrative lacked the visceral intensity of conventional opera, with characters appearing too passive or enigmatic.” A good many writers objected to Debussy’s harmonic language and lack of melody.

As a critic wrote in 1902, “M. Debussy’s score of Pelléas defies description, being such a refined concatenation of sounds that not the faintest impression is made on the ear. The composer’s system is to ignore melody altogether; his personages do not sing but talk in a sort of lilting voice to a vague musical accompaniment of the text…The effect is quite bewildering, almost amusing in its absurdity.”

Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande, Act III, scene 1

Decadence

Critics like Camille Saint-Saëns famously derided Debussy’s innovations of musical language, reportedly calling his music “decadent” and accusing it of “abandoning the clarity and structural rigor of classical tonality in favour of vague, impressionistic soundscapes.”

And Arthur Pougin wrote in Le Méneststrel, “Rhythm, melody, tonality, these are three things unknown to Monsieur Debussy and deliberately disdained by him… What a collection of dissonances, sevenths and ninths, ascending with energy, even disjunct intervals! No, decidedly, I will never agree with these anarchists of music!”

Not to be outdone, the Musical Courier reports on 16 July 1902, “In Debussy’s opera Pelléas, consecutive fifths, octaves, ninths, and sevenths abound in flocks, and not only by pairs, but in whole passages of such in harmonious chords. Such progressions sound awful, as when the dentist touches the nerve of a sensitive tooth.”

Claude Debussy: Pelléas et Mélisande, Act III, scene 4

L’Après-midi d’un faune

Ninjinsky In Afternoon Of A Faun

In a letter to Maurice Emmanuel from 4 August 1920, Saint-Saëns writes. “The Prelude L’Après-midi d’un faune has pretty sonority, but one does not find in it the least musical idea, properly speaking; it resembles a piece of music as the palette used by an artist in his work resembles a picture. Debussy did not create a style; he cultivated an absence of style, logic, and common sense.”

While praised for its evocative orchestration and innovative harmonic language, L’après-midi d’un faune was attacked for its perceived lack of formal structure. It was argued that its free-flowing, dreamlike quality sacrificed the clear thematic development and architectural coherence expected in symphonic works. Pierre Lalo called it “vague and elusive,” and suggested the reliance on mood and colour over conventional melody or rhythmic drive “left it insubstantial and aimless.”

Additionally, the work’s subtle eroticism and departure from tonal resolution unsettled conservative audiences and critics, who found its harmonic ambiguity and lack of a traditional climax either perplexing or unsatisfying.

Claude Debussy: L’Après-midi d’un faune

Erotic Spasms

Louis Elson published the following musical invective in the Boston Daily Advertiser in February 1904. “Debussy’s L’Après-midi d’un faune was a strong example of modern ugliness. The faun must have had a terrible afternoon, for the poor beast brayed on muted horns and whinnied on flutes, and avoided all traces of soothing melody, until the audience began to share his sorrows… with all these erratic and erotic spasms does it indicate that our music is going through a transition state. When will the melodist of the future arrive?”

And a reviewer for the Referee in London writes in 1904, “A vacuum has been described as nothing shut up in a box, and the prelude entitled L’Après-midi d’un faune may aptly be described as nothing, expressed in music. The subject certainly affords opportunity for the exercise of the composer’s imagination, but he appears to have come to the conclusion that the fortunate faun was not thinking about anything at all…”

These criticisms, though often overshadowed by the Prélude’s enduring influence, highlight the polarising reception of Debussy’s radical aesthetic at the time of its premiere. As we read in the Boston Daily Advertiser on 2 January 1905, “Poor Debussy, sandwiched in between Brahms and Beethoven, seemed weaker than usual. We cannot feel that all this extreme ecstasy is natural; it seems forced and hysterical, it is musical absinthe; there are moments when the suffering Faun seems to need a veterinary surgeon.”

Claude Debussy: L’Après-midi d’un faune (arr. Gryaznov)

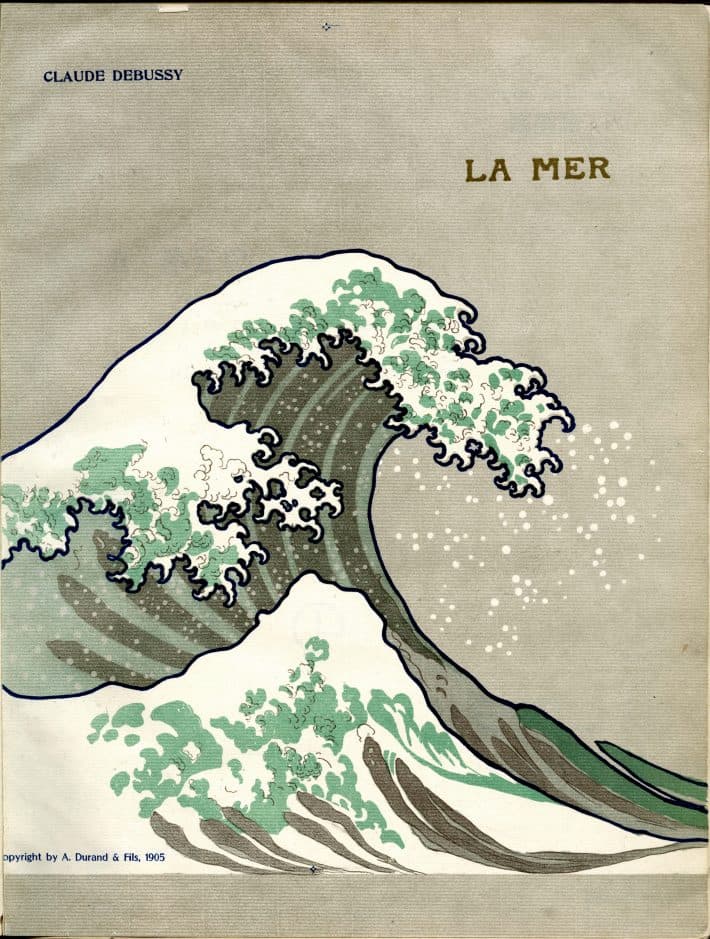

La Mer

Cover image of La Mer featuring the famous “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” by Hokusai

Debussy’s La Mer, his three-movement orchestral masterpiece, is often hailed as the pinnacle of musical impressionism, but it faced its share of criticism despite its celebrated status. Some attacked its apparent lack of structural rigour that prioritised atmospheric effect over clear thematic development. For some, it was “a series of sensations rather than a symphonic work.”

A critic in Boston asked whether “it is possible that Debussy did not intend to call it “Le Mal de Mer,” which would at once make the tone-picture as clear as day. It is a series of symphonic pictures of sea-sickness. The first movement is Headache. The second is Doubt, picturing moments of dread suspense, whether or not. The third movement, with its explosions and rumblings, now has a self-evident purpose. The hero is endeavouring to throw up his boot-heels!”

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “De l’aube à midi sur la mer”

Sea-Sickness

The London Times reports on 3 February 1908, “ M. Claude Debussy… directed the first performance in England of his symphonic sketches, called collectively La Mer… As in all his mature works, it is obvious that he renounces melody as definitely as Alberich renounced love; whether the ultimate object of that renunciation is the same we do not know as yet. For perfect enjoyment of this music, there is no attitude of mind more to be recommended than the passive, unintelligent rumination, as long as actual sleep can be avoided.”

Even composers like Vincent d’Indy criticised the orchestration’s brilliance as superficial, claiming its “vivid depictions of nature verged on programmatic gimmickry rather than substantive musical argument.” In the event, for some critics, the vivid pictorialism overshadowed its emotional resonance.

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “Jeux de vagues” (Ulster Orchestra; Yan Pascal Tortelier, cond.)

Unremarkable Orchestration

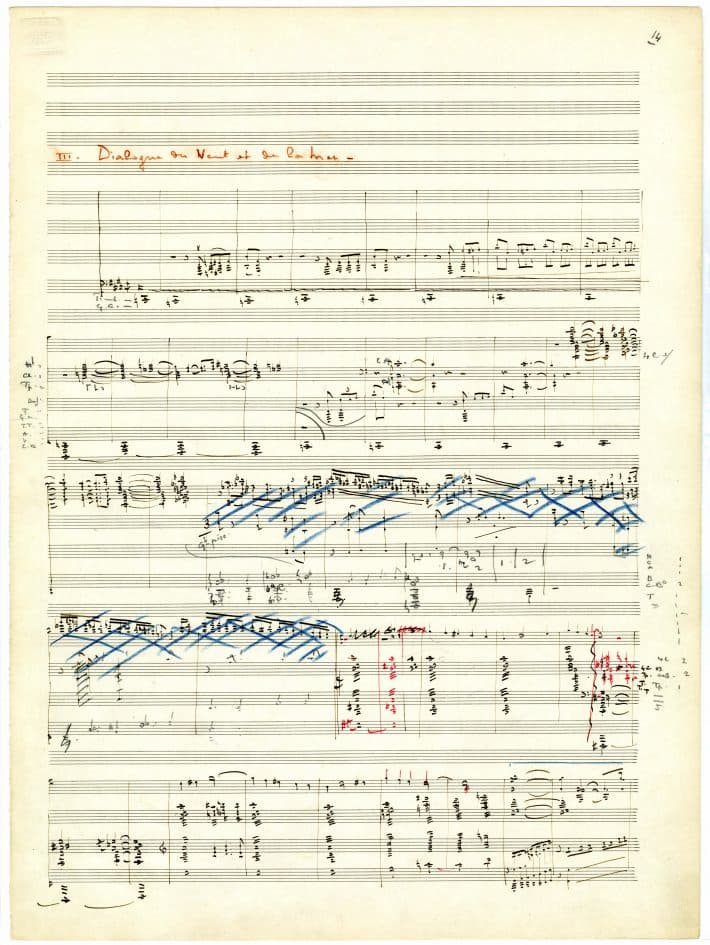

Manuscript of La Mer third movement

The New York Post writes on 22 March 1907, “Debussy’s music is the dreariest kind of rubbish. Does anybody for a moment doubt that Debussy would not write such chaotic, meaningless, cacophonous, ungrammatical stuff if he could invent a melody? Even his orchestration is not particularly remarkable.”

The work was accused of lacking intellectual depth, and the harmonic language, with its frequent use of whole-tone scales, unresolved dissonances, and shifting tonal centres, drew fire from detractors who found it disorienting or overly ambiguous. Debussy was accused of abandoning tonal clarity for a “hazy” aesthetic.

A critic writes, “M. Debussy wrote three tonal pictures under the general title of The Sea. It is safe to say that few understood what they heard, and few heard anything they understood. There are no themes distinct and strong enough to be called themes. There is nothing in the way of even a brief motif that can be grasped securely enough by the ear and brain to serve as a guiding line through the tonal maze. There is no end of queer and unusual effects in orchestration, no end of harmonic combinations and progressions that are so unusual that they sound hideously ugly.”

Claude Debussy: La Mer, “Dialogue du vent et de la mer”

“Debussy School”

When it came to the broader influence of Debussy’s techniques on subsequent composers and the establishment of a so-called “Debussy school,” opinions greatly varied. Vincent d’Indy argued that Debussy’s rejection of classical forms and reliance on fluid, evocative textures set a dangerous precedent, encouraging imitators to prioritise sensory effect over rigorous development. And even Igor Stravinsky, generally an admirer, suggested that “impressionist method was overly static,” suggesting it risked stagnation.

Paul Flat wrote in 1909, “I believe that there is an enormous amount of snobbism and bluff in the reputation of this musician. The Debussyan formula is less than any other capable of creating a school. But this instance has proved abundantly that it can create counterfeit. However, all these makers of pastiche in a style in which artifice already plays such a great role have accomplished nothing but an art that is empty, cold, abstract, the deadest art that has appeared in a long time. All preconceived imitation is deplorable in art. But there is none that is so fruitless as the imitation in Debussysm.”

Claude Debussy: Jeux

Amorphous Art

Portrait of Claude Debussy by Marcel Baschet, 1884

Camille Bellaigue asked in 1909, “What is the real importance and what is and ought to be the role of M. Claude Debussy in the contemporary evolution of music? I believe that this importance is infinitesimal, and I wish that his role would also be that. Does he represent a fertile innovation? No! A method and a direction susceptible to establish a school, and should he actually establish a school? No, and again no!”

And an anonymous critic added, “This amorphous art, so little virile, seems to be made specially for tired senses. It is something both bitter and sweetish, which evokes somehow the idea of falseness and fraud. It is a diminutive art which some naively proclaim as the art of the future. However, it reduces itself to musical dust, a mosaic of chords, a lilliputian art for dwarfish humanity.”

Debussy’s music also faced criticism within modernist circles. The serialists of the early 20th century dismissed Debussy’s harmonic innovations as insufficiently systematic, arguing that his intuitive, colour-driven style resisted the kind of intellectual framework needed to advance music beyond Romanticism.

Followers of Debussy’s style of composition included to some extent Maurice Ravel, Frederick Delius, Cyril Scott, and Charles Griffes, who more or less heavily leaned on the dreamy and coloristic qualities of Debussy’s method of crafting delicate and harmonically ambiguous soundscapes.

Claude Debussy: Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp

Polarising Figure

Grave of Claude Debussy

During his lifetime, Debussy was a polarising figure, viewed with a mix of admiration, bewilderment, and outright hostility depending on the audience and context. To his supporters, he was a visionary genius who liberated music from the constraints of Romantic excess and Germanic formalism.

To his critics, as Alfred Mortier writes in the Rubriques Nouvelles in 1909, “Recent music produces on me the effect of a richly adorned mummy which keeps human appearance only by great reinforcement of the ingredients. It is no longer composition, it is decomposition.

The music of Debussy has the attractiveness of a pretty tubercular maiden, with her languorous glances, anaemic gestures, whose perversity has the charm of one marked for death. A symphony, a piece of music, are organisms. A Debussyan organism reminds us of the jellyfish whose translucid substance lights up brilliantly at the touch of a sunlit wave, but which will never be anything but a protozoan. All this lacks fibre and blood. I have the sensation of originality covering up a kind of impotence.”

By the time of Debussy’s death on 25 March 1918, he was recognised as a transformative force, though not without lingering resistance. His lifetime was a battleground between innovation and orthodoxy, with Debussy emerging as a symbol of both progress and controversy.

Today, the conversation about Debussy has evolved. While the works are still studied, critics and audiences are more preoccupied with execution. This reflects broader trends in classical music culture. Debussy’s music isn’t controversial anymore, as the lens has turned to performers as the variable. It’s no longer a question if Debussy’s music is any good, but a question of did we get Debussy right?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter