It is not commonly known that Franz Liszt composed well over eighty songs in German, French, Italian, Hungarian, Russian, and English. While his settings of German poetry predominate, “his songs in French are among the most significant works, especially those set to poems by Victor Hugo.” His seven Hugo settings date from between 1842 and 1844; however, Liszt revised and crafted alternate versions of four poems fifteen years later. According to some sources, Liszt was personally acquainted with Victor Hugo and he “invited him to his concerts.” Liszt read French Romantic literature throughout his life, and like many other composers, he was drawn to the powerful verses of Hugo. Liszt’s initial Hugo settings date from a time when Liszt was busily touring Europe as a piano virtuoso. As such, his early version is frequently called “piano works with vocal accompaniment.” While they initially reflect the musical instincts of a performing pianist, his revised versions balance the roles of the voice and piano, “creating simpler textures that rely more on harmonic expressiveness than pianistic muscle.” Hugo published Oh! quand je dors (Ah, while I sleep) in 1840 in his volume of poetry Les rayons et les ombres. The relationship of Petrarch and Laura likely reflects the poet’s connection with Juliette Drouet, and by extension, the relationship of Liszt and Marie d’Agoult.

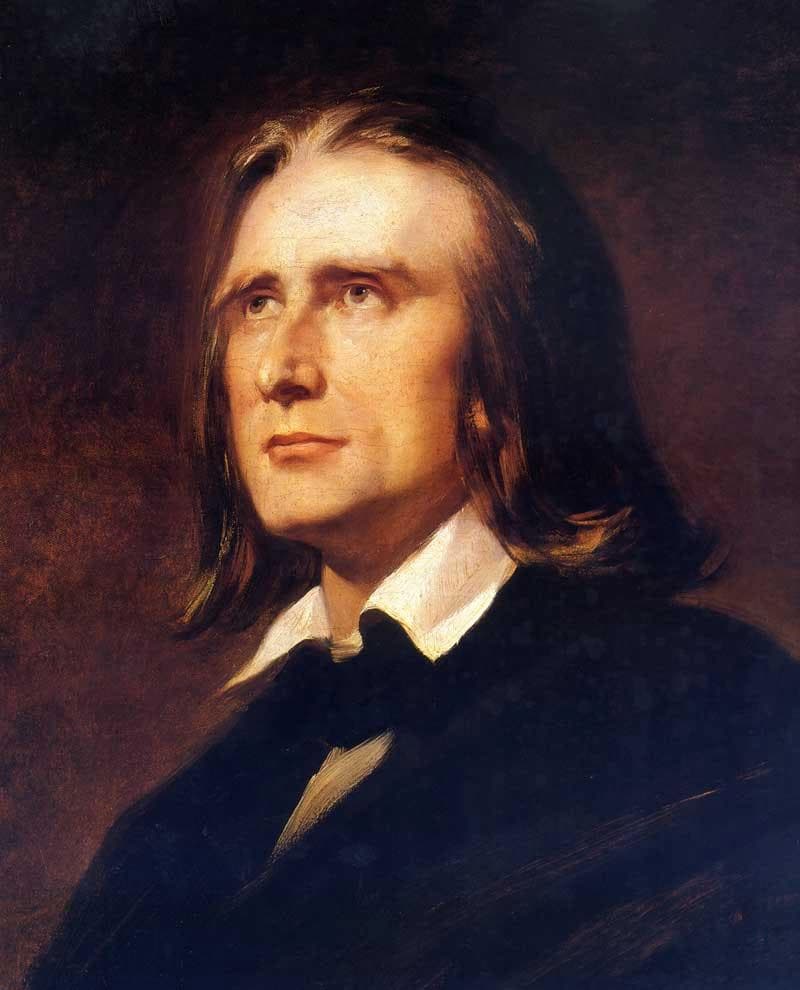

Portrait of Franz Liszt by Wilhelm von Kaulbach

Oh! quand je dors, viens auprès de ma couche,

Comme à Pétrarque apparaissait Laura,

Et qu’en passant ton haleine me touche…

Soudain ma bouche

S’ent r’ouvrira!

Sur mon front morne où peut-être s’achève

Un songe noir qui trop longtemps dura,

Que ton regard comme un astre se lève…

Soudain mon rêve

Rayonnera!

Puis sur ma lèvre où voltige une flamme,

Éclair d’amour que Dieu même épura,

Pose un baiser, et d’ange deviens femme…

Soudain mon âme

S’éveillera!

Oh viens! Comme à Pétrarque apparaissait Laura!

Ah! while I sleep, come close to where I lie,

As Laura once appeared to Petrarch,

And in passing let your breath touch me…

At once my lips

Will open!

On my mournful brow, where a dismal dream

That lasted too long is hopefully ending

Let your glance like a star be lifted…

At once my dream

Will shine!

Then on my lips where the flame flickers

A flash of love God himself has purified,

Place your kiss, and be transformed from angel into woman…

Suddenly my spirit

Will wake!

Oh come! As Laura appeared to Petrarch!

Franz Liszt: Oh! Quand je dors (1st version) (Angela Gheorghiu, soprano; Martin Martineau, piano)

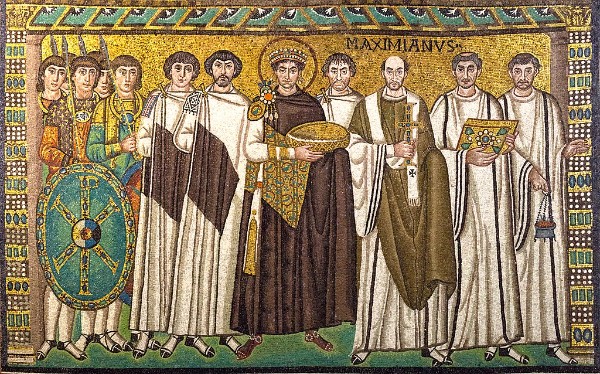

Portrait of Victor Hugo against the backdrop of Notre-Dame de Reims – Jean Alaux, Maison de Victor Hugo – Hauteville House, 1822.

Liszt’s first version is full of extended gnarly pianism and compared to the revised version fashioned 15 years later, it is also more expansive. While the initial version presents a substantially shortened coda, both versions rely on a four-note motive presented in the piano in the opening measure. The supporting harmonies differ slightly, and the melodic line floats gently, in the case of the second version in double rhythmic values, over subtly changing chromatic harmonies. As previously mentioned, the texture becomes simpler and thinner, with the piano accompaniment shining in a much more transparent pattern. In his revision, Liszt rewrote the entire second verse, presenting a different melody with a supporting harmony that never masks the pure tone colors of the voice. When Liszt wrote this song in 1842, he naturally liked to show off his brilliant technique. As such, “in the last part of the second stanza, the piano is soloistic and independent from the vocal line; the piano sets the mood instead of the voice part. In his later version, Liszt included a vocal cadenza with piano accompaniment instead.”

Franz Liszt: Oh! Quand je dors (2nd version) (Szabolcs Brickner, tenor; Emese Virag, piano)

Portrait of Marie d’Agoult by Henri Lehmann, 1843

Originally, Victor Hugo titled the love song Enfant, si j’étais roi as Une femme. In the event, it was published in a collection titled Les Feuilles d’Automne in 1831. In this collection, Hugo relied on three basic levels of inspiration, foremost among them a sense of melancholy and resignation, “following the betrayal of his wife and his friend.” As the poet looks at his past, he consoles himself with the spectacle of childhood. Listening to the voices of nature and humanity, the poet “puts God in the center of everything like a sonorous echo.” In this collection, Hugo also castigates all forms of political oppressions, and “moved by the thousand objects of creation that suffer,” he celebrates the idea of charity. In Enfant, si j’étais roi, a lover swears that if he were king, he would renounce all riches and power for just one glance, and if he were God, he would give up command over space, eternity, chaos, angels and demons for just one kiss.

Portrait of Victor Hugo by Achille Deveria

Enfant, si j’étais roi, je donnerais l’empire,

Et mon char, et mon sceptre, et mon peuple à genoux,

Et ma couronne d’or, et mes bains de porphyre,

Et mes flottes à qui la mer ne peut suffire,

Pour un regard de vous!

Si j’étais Dieu, la terre et l’air avec les ondes,

Les anges, les démons courbés devant ma loi,

Et le profond chaos aux entrailles fécondes,

L’éternité, l’espace et les cieux et les mondes

Pour un baiser de toi!

Child, if I were king, I would give the empire,

And my chariot, and my scepter, and my kneeling people,

And my crown of gold, and my porphyry bath,

And my fleets that the sea cannot contain,

For one glance from you!

If I were God, the earth and the air with the waves,

The angels, the demons bowed before my rule,

And the chaos of the fertile deep,

Eternity, space, the heavens and the universe

For a kiss from you!

Franz Liszt: Enfant, si jétais roi (1st version) (Dennis O’Neill, tenor; Adrian Farmer, piano)

Portrait of Juliette Drouet by Charles-Emile-Callande de Champmartin

Liszt’s original setting and the revision, roughly 20 years later, disclose a number of fundamental differences. Foremost among them is a difference in meter, changing from 3/4 to 4/4. “In spite of the different meters, however, Liszt maintained the syllabic integrity of the text by lengthening notes and adding rests.” In the original version, softly chattering figures in the piano become heavier, and emphatic chords grow exponentially before being unleashed in a powerful chromatic bass. “But the invocation of a single kiss at the end brings consummate tenderness, the final A-flat major passage colored and deepened by Liszt’s use of the flattened sixth degree of the scale, both melodically and harmonically.” In the original version, the register of the voice is occasionally so low that the vigorous piano accompaniment can easily overwhelm the voice. His second version, once again, revises the song towards greater concision and a more delicate texture. “The previously hyperbolic accompaniment of the 1844 version is trimmed down considerably. Here the rhythmically off-centre semitone figures in the left hand and the thrumming repeated chords in the right beautifully bespeak passion’s restless energy; after a rampaging episode of cosmic thunder, Liszt returns to Love, in a final cadence made irresistible by hints of the parallel minor.”

Franz Liszt: Enfant, si jétais roi (2st version) (Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Irwin Gage, piano)

Portrait of Franz Liszt, 1832

Victor Hugo once put an advertisement in Le Figaro begging composers not “to set tones alongside my words.” Thankfully, composers did not heed his words, irresistibly drawn to his beautiful poems. Comment disaient-ils appears in Hugo’s collection Les rayons et les ombres, and it was set to music by Lalo, Bizet, Camille Saint-Saëns, Massenet, Franz Liszt and others. The original poem is entitled Autre guitare, providing an immediate suggestion of a Spanish subject.

Comment, disaient-ils,

Avec nos nacelles,

Fuir les alguazils?

Ramez! Ramez! disaient-elles.

Comment, disaient-ils,

Oublier querelles,

Misère et périls?

Dormez! Dormez! disaient-elles.

Comment, disaient-ils,

Enchanter les belles

Sans philtres subtils?

Aimez! Aimez! disaient-elles.

Ramez! Dormez! Aimez! disaient-elles.

How, said the men,

in our small boat,

can we free from the police?

Row! Row! the women said.

How, said the men,

can we forget quarrels

Poverty and danger?

Sleep! Sleep! the women said.

How, said the men,

can we charm beautiful women

without rare potions?

Love! Love! the women said.

Row! Sleep! Love! the women said.

Franz Liszt: Comment disaient-ils (1st version) (Brigitte Fassbaender, mezzo-soprano; Irwin Gage, piano)

Victor Hugo, Vanity Fair, 20 September, 1879

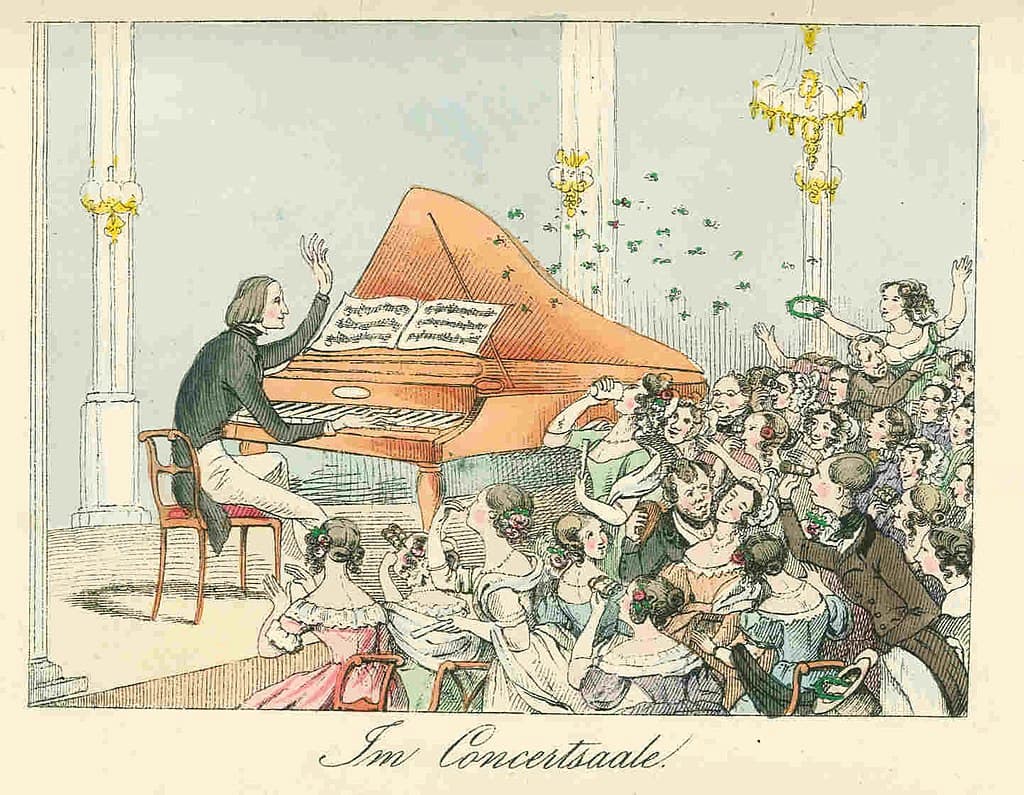

At the beginning, Liszt lets the pianist accompany this serenade “quasi chitarra” (like a guitar), and adds staccato indications. In addition, the song ends with quickly arpeggiated chords in the accompaniment. As the narrator tells of the dialogue between men and woman, Liszt clearly differentiate the women’s characters from the men’s in the accompaniment. Staccato guitar-like figures change to legato arpeggiated chords whenever the women answer the men’s questions. “Liszt also uses modulation and changes in tempo to highlight the distinction more effectively.” In his second version, Liszt drastically changed both the voice part and piano accompaniment. The changes are so dramatic that a scholar “considered the two versions good examples to show the development of Liszt’s style as a song composer between 1848 and 1859.” As in earlier settings, the revised version is simplified, with the texture thinned dramatically and placed in a higher register, essentially to accentuate a guitar-like accompaniment. In terms of setting the poetry, a scholar has suggested that the “second version shows more effective contrast rhythmically as well as melodically.” Although the song unfolds in strophic form, Liszt does not adhere to exact repetition as the key of each verse modulates to a different key. Additional difference between the two versions of Comment disaient-ils surface in the piano interludes. “In the 1842 version, the three measures between the questions and answers are marked “rinforzando” followed by “ritardando and diminuendo. The exact opposite guides the 1859 version, when the “rinforzande” is followed with “accelerando” and “crescendo.” In his earlier version, the interludes segue into the entrance of the women’s voice, while there are one-measure silences before the women’s answers in the later song.

Franz Liszt: Comment disaient-ils (2nd version) (Diana Damrau, soprano; Helmut Deutsch, piano)

Caricature of Liszt in the concert hall

Hugo published his volume of poetry Les voix intérieures (Interior Voices) in 1837. It contains thirty-two poems preceded by a preface that discloses “Hugo’s penchant for the magical number three, which is used to simplistically explain the order of life and the universe… It presents man as heart, nature as soul, and events as mind.” Hugo apparently had great respect for people, but nothing but scorn for the crowd. True to the title of the collection, Hugo explains that everyone “has music within if only we could learn to listen to it.” Thus, the interior voices are another manner of communication, but this requires mediation. Thematically, the collection features a great assortment of expressions, ranging from the “poet’s love for Juliette Drouet, dazzling accolades to family life, his great love of nature and his fear of it, as well as a number of pessimistic poems that show his concern for the welfare of the poor in contrast with the idle, cynical, and decadent rich.” La tombe et la rose begins with a narrator’s voice and proceeds as a dialogue between the tomb and the rose.

La tombe dit à la rose:

Des pleur dont l’aube t’arrose

Que fais-tu, fleur des amours?

La rose dit à la tombe:

Que fais-tu de ce qui tombe

Dans ton gouffre ouvert toujours?

La rose dit: Tombeau sombre,

De ces pleurs je fais dans l’ombre

Un parfum d’ambre et de miel.

La tombe dit: Fleur plaintive,

De chaque âme qui m’arrive

Je fais un ange du ciel.

The tomb says to the rose:

With the tears with which the dawn sprinkles you

What do you make, flower of love?

The rose says to the tomb:

What do you make with one who falls

In your ever-open abyss?

The rose says: Gloomy tomb,

From these tears, I make in the shadows

A perfume of amber and of honey.

The tomb says: Pitiful flower,

With each soul that arrives in me

I make an angel of heaven.

Liszt composed his setting in 1844, but unlike the songs sampled thus far, he did not rework his setting at a later date. The question and answer topoi clearly appealed to Liszt, whose triplet chords in the low register provide a haunting funeral March atmosphere. The poem delineates between three voices, the narrator, the rose, and the tomb, with Liszt making a clear distinction between these voices in his timbre and melody. The narrator sounds an ascending perfect fourth sliding into a declamatory melody, reflecting a sense of neutrality. Liszt’s early songs have been criticized for their “formlessness, insensitivity to texts, and bombastic and boorish accompaniments.” Liszt was always self-critical of his gift as a song composer, and he expensively revised some of these immature efforts. In La tombe et la rose, however, the original version already demonstrates a more subtle awareness of the text, ‘extreme delicacy at times, and original, yet a clear formal design.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: La tombe et la rose (Janina Baechle, mezzo-soprano; Charles Spencer, piano)