One of my all-time feel-good movies is the animated musical fantasy film “The Little Mermaid.” Originally released in 1989 by Walt Disney Pictures, the movie takes us to the kingdom of Atlantica. Princess Ariel, a 16-year-old mermaid, is unhappy with her underwater life and fascinated by the human world. She falls in love with the human Prince Eric, and after much adventure, Ariel permanently turns into a human and marries her Prince.

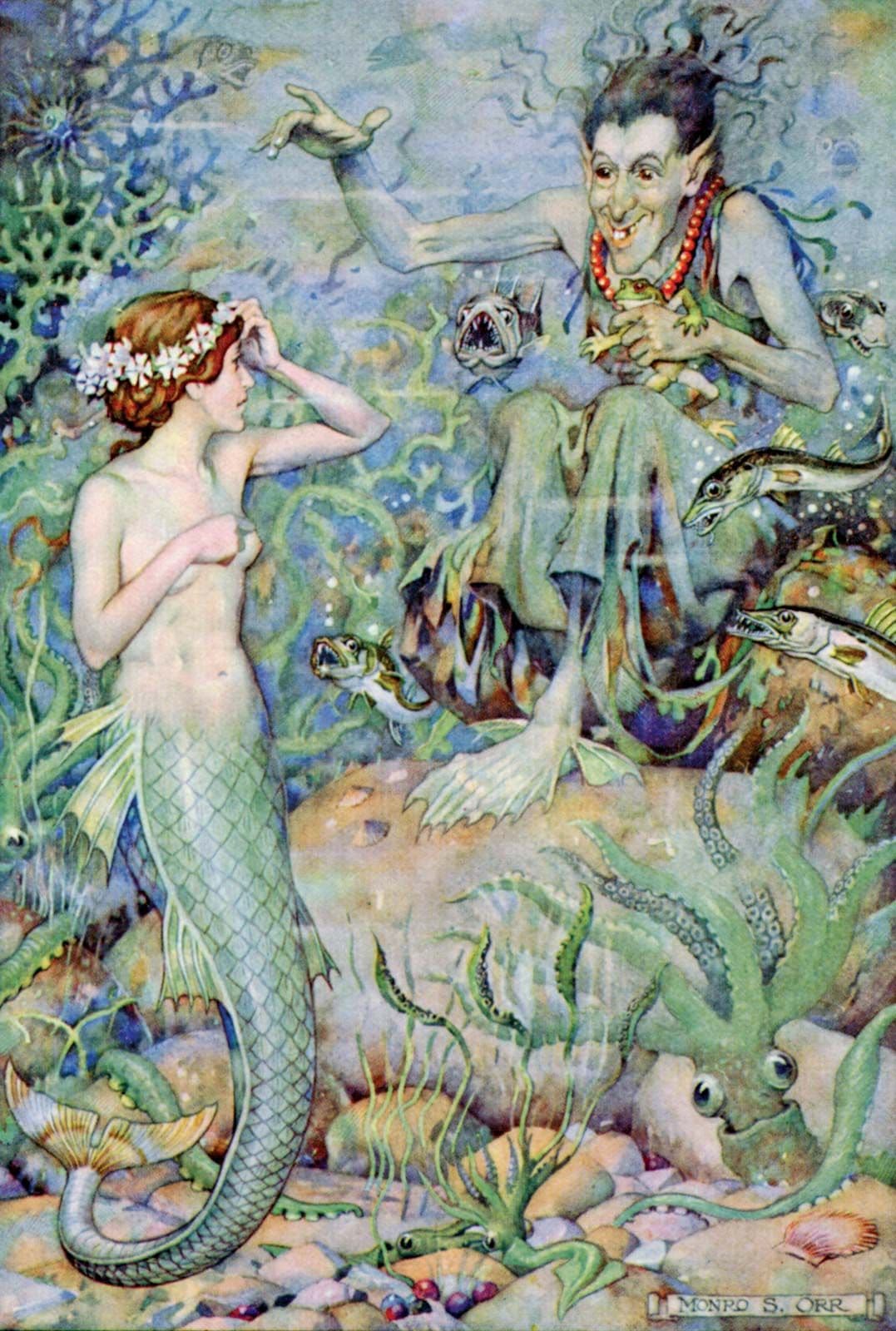

Illustration in Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid”

Thirty years later, in 2023, Walt Disney Pictures released a remake of that movie, this time featuring real actors. The plot once again features the young mermaid who makes a deal with a sea witch to trade her beautiful voice for human legs so that she can discover the world above water and impress a Prince.

Disney: The Little Mermaid

Mermaids

So what is actually a mermaid? Basically, it is a fabled marine creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, and in Europe, they were natural beings, like fairies, with magical prophetic powers. Also occasionally called sirens, they loved music and singing.

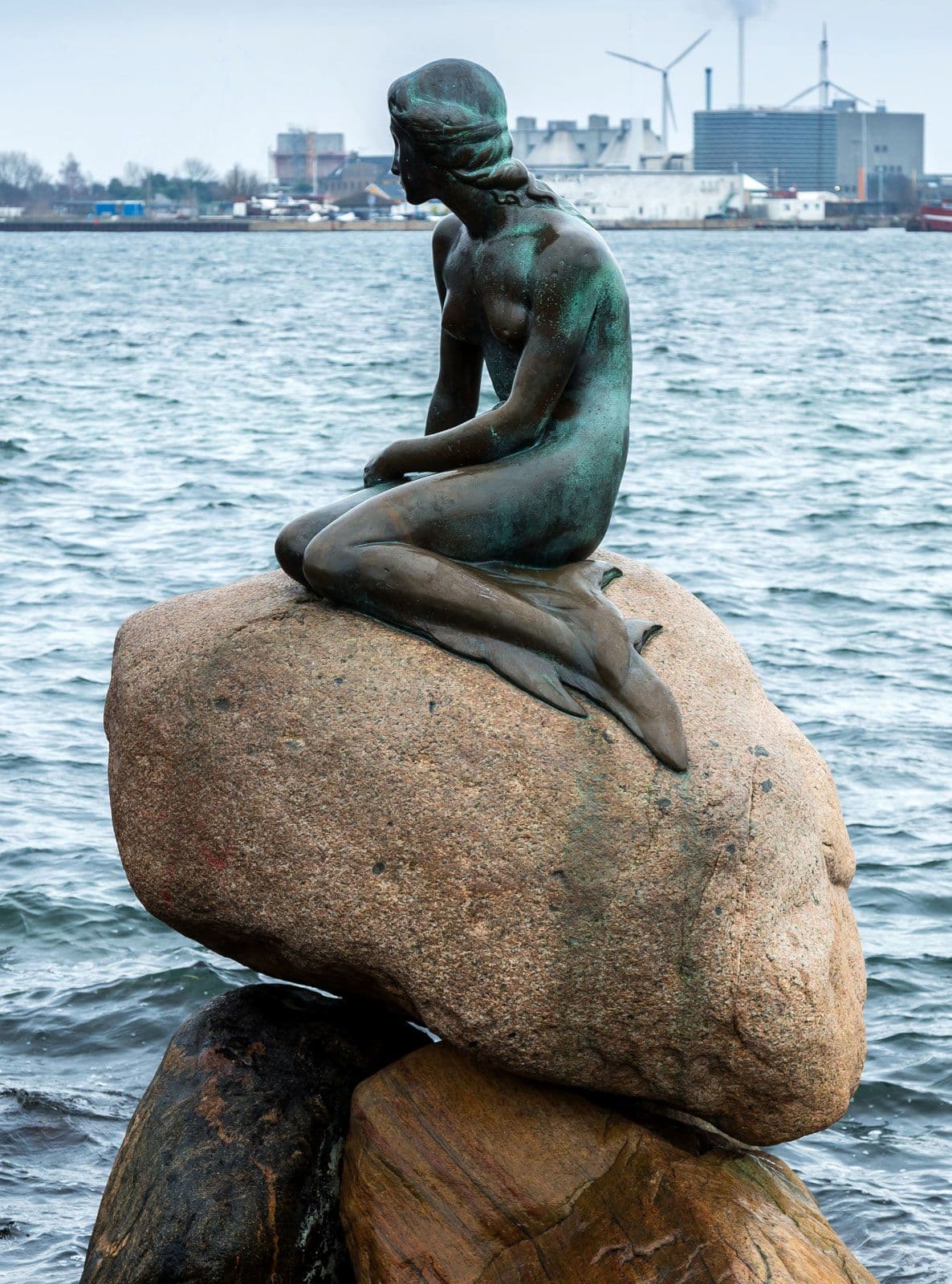

The Little Mermaid (1913) – sculpture by sculptor Edvard Eriksen

Some folktales record marriages between mermaids, who might assume human form and men. And while mermaids are often kind, they can also be dangerous. If offended, they are said to cause floods, shipwrecks, or other disasters. In European folklore, the concept of mermaids as beautiful and seductive singers seems to originate in Greek mythology. And it might be hard to believe, but actual mermaid sightings have still been reported in 2023.

The Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen

As part of a collection of fairy tales for children, Hans Christian Andersen published “The Little Mermaid” in 1837. This enticing story follows the journey of a young mermaid who is willing to give up her life in the sea to gain a human soul. It is one of Andersen’s most beloved fairy tales, and it inspired books, comics, animations, films, operas, and much classical music. That’s all very exciting, so we decided to put together a little blog featuring music associated with mermaids.

Niels Gade: Havfruesang (Mermaid Song) (Ficta Musica, choir; Bo Holten, cond.)

Franz Joseph Haydn: “The Mermaid’s Song”

Haydn in London

Franz Joseph Hadyn made a couple of trips to England, and he was soon engaged to arrange a number of folksongs. The country was caught up in a great passion for collecting these melodies, and the publisher William Napier was looking for musical arrangements of his “100 Scottish Folksongs.” Essentially, Haydn needed to provide suitable accompaniments for the “wild and pathetic sweetness of these melodies.” In addition, Haydn was also busy composing two sets of six “Original Canzonettas” primarily for the profitable amateur market.

It has been suggested that Haydn was deeply inspired by Anne Hunter, the widow of the famous surgeon Sir John Hunter. Anne fancied herself a polished poetess writing in the taste of the day. Critics have suggested that her verses were unoriginal, usually soulful and sentimental, and with a dash of Gothic gloom. Each of the six Haydn Canzonettas opens with a song to the sea, and “The Mermaid’s Song” was certainly inspired by the first line of text, “Now the dancing sunbeams play.” Haydn writes a shimmering and glittering piano prelude before the Mermaid calls, “Follow me!” luring the listener into her underwater realm.

Franz Joseph Haydn: 6 Original Canzonettas, Book 1, No. 1 “The Mermaid’s Song” (Julie Kaufmann, soprano; Donald Sulzen, piano)

Eugen d’Albert: Little Mermaid

Eugen and Hermine d’Albert

Haydn had no way of knowing Andersen’s “Little Mermaid,” but Eugen d’Albert (1864-1932) certainly did. In 1895, d’Albert married the soprano Hermine Finck, who had created the role of “The Witch” in Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel. In fact, she became the principal interpreter of her husband’s vocal music, and in 1897, d’Albert was working to showcase his wife in a cantata for soprano and orchestra loosely based on Andersen’s fairy tale “The Little Mermaid.”

D’Albert worked on the score, deeply under the musical influence of Richard Wagner, during a summer holiday in Bavaria. He had engaged James Grun, the librettist of the first two operas by Hans Pfitzner to versify the Andersen fairy tale. The story takes a slightly different ending, as the mermaid is failing to secure the love of her prince in marriage and is only saved from death by a final transformation into a bird. D’Albert’s marriage to Finck also did not end well, as the couple divorced in 1911.

Eugen d’Albert: Little Mermaid, Op. 15 (Viktorija Kaminskaite, soprano; Leipzig MDR Symphony Orchestra; Jun Märkl, cond.)

Enrique Granados: “La Sirena”

Enrique Granados in 1914

During his apprenticeship with Felipe Pedrell from about 1884 to 1895, Enrique Granados (1867-1916) was striving to find his own individual artistic personality. Many of his compositions are “sketches or brief compositions characterized by an unfocused formal structure and harmonic ambiguity.” Typical for a young composer, he explored themes of nature and varied emotions in salon-style compositions, which he probably did not intend to publish. However, he did probably perform them in the Conde family salon, the home of his first patron. “La Sirena” is a light-hearted yet passionate and melancholy miniature offering introverted and luminous harmonies with a rich palette of pianistic colour that gently draws us into the world of the mermaid.

Enrique Granados: “La Sirena” (The Mermaid) (Douglas Riva, piano)

Lydia Kakabadse: The Mermaid

Lydia Kakabadse

As I said in my introduction, mermaids still hold relevance today. The composer Lydia Kakabadse developed a distinct musical style combining open triad and Gothic features mixed with Middle Eastern traits. And she set to music her own story of “The Mermaid,” scored for mezzo-soprano, narrator, piano, and strings. Persephone, a mermaid, is much loved by her fellow sea creatures, and her song imitates cascading waves. The “Calling Song” is sung whenever she wishes to call her friends, the cherubs, and the opening scene ends with a great sense of foreboding.

Pirates capture Persephone, and the boat sails away while she is singing the “Mermaid Song.” Imprisoned and languished, Persephone sings her “Calling Song” as the boat takes her evermore further from her beloved cherubs. However, the cherubs are led to the pirate boat by that enchanted song, and they manage to overthrow the pirates and set her free. Fully recovered from her ordeal, a joyous Persephone hums the Mermaid’s Song, accompanied by the gentle rippling effect of the piano.

Lydia Kakabadse: The Mermaid (Kit Hesketh-Harvey, narrator; Clare McCaldin, mezzo-soprano; Madeleine Easton, violin; Sarah-Jane Bradley, viola; Bozidar Vukotic, cello; Ben Griffiths, double bass; Christian Wilson, piano; George Vass, cond.)

Antonín Dvořák: Rusalka, “Song to the Moon”

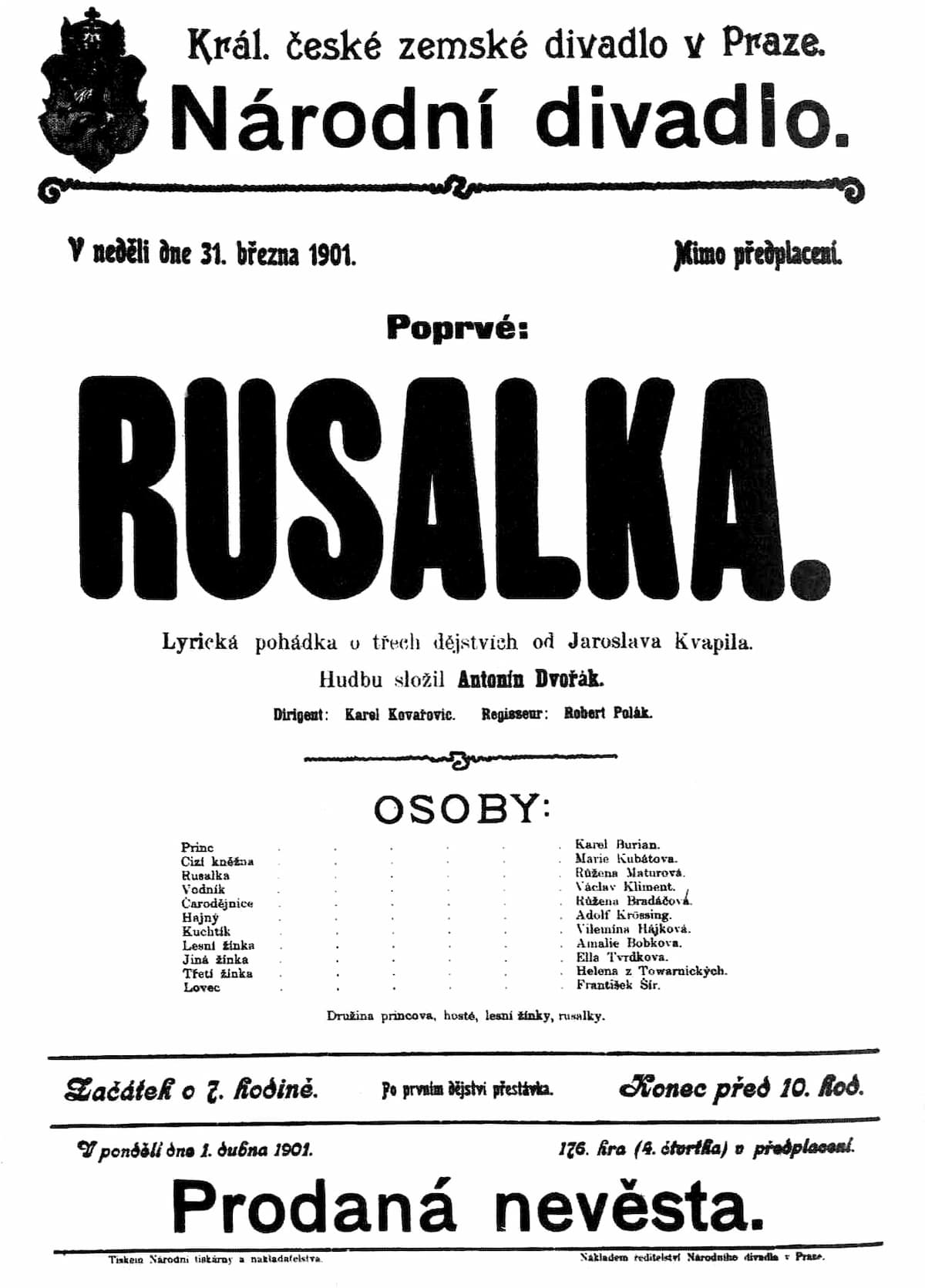

Poster for the premiere of Rusalka in Prague, 31 March, 1901

With his opera Rusalka, Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) single-handedly defined Czech opera. “Rusalka” is the Czech version of the popular fairy tale, but Rusalka is not a mermaid but a water spirit, also called a water nymph. However, like the Little Mermaid,

Rusalka falls in love with a human Prince. In exchange for her voice, a witch turns her into a human. She must now win and keep the Prince’s love, or else there will be disastrous consequences for them both. The Prince is rather unhappy that his bride-to-be is unable to speak, and he accepts the hand of a Foreign Princess. Rusalka, meanwhile, obeying the curse of the witch, is doomed to live in the depths of the lake forever.

The “Song to the Moon” takes place at the very beginning of the story when Rusalka, still a nymph, sings a nocturnal serenade. Dvořák’s skillful orchestration, relying on lush harmonic depth, immediately evokes a moonlit mystical forest. Rusalka’s “Moon Aria” is steeped in a deep sense of melancholy. Infused with characteristic folk rhythms and melodic turns that emphasis a modal musical language, the music perfectly portrays Rusalka’s longing and desire.

Antonín Dvořák: Rusalka, “Song to the Moon”

Alexander Zemlinsky: The Mermaid

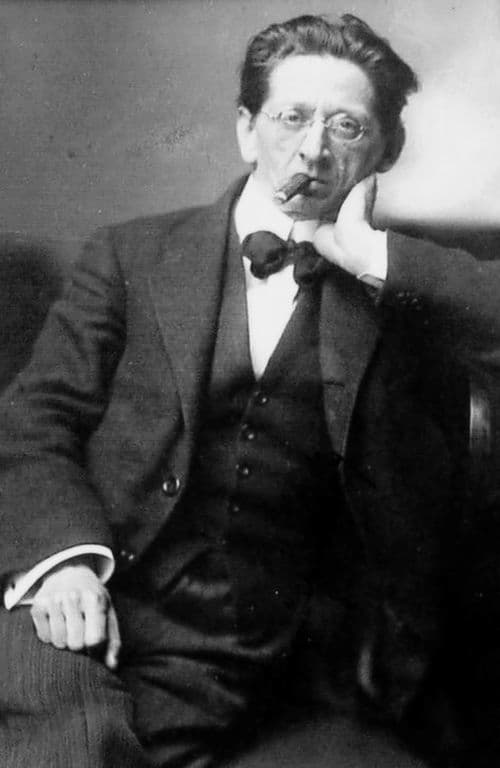

Alexander von Zemlinsky

In 1902, Alexander Zemlinsky and his student Arnold Schoenberg decided on a musical competition. Essentially, they were trying to see who could write a more appealing symphonic poem. Schoenberg selected Maurice Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande while Zemlinsky turned to “The Little Mermaid” by Andersen. Both works were presented to the public on the same program in 1905, with the two composers conducting their own work. Zemlinsky’s “Die Seejungfrau” was an unqualified success, but nobody liked Schoenberg’s Pelléas.

Zemlinsky first drafted the work in a single movement divided into two parts, each one containing two episodes. The first part explores the world beneath the waves and then finds the mermaid rescuing the prince in the storm. In the second part, we experience the mermaid’s longing and her encounter with the sea witch before we proceed to the wedding of the prince. You see, the prince ends up marrying a human princess, and as a consequence, the mermaid is doomed to meet the fate of all mermaids when they die, which is to dissolve into sea foam. Zemlinsky subsequently expanded the work into three parts and referred to it as a symphonic poem, but for the premiere, he changed the title to “Fantasy for Orchestra.”

Alma Mahler in 1909 © Wikipedia

It is a beautiful work of panoramic moods and colours, and “the composer’s command of orchestral colour is indeed admirable, summoning up sensations of underwater undulation and cavorting creatures in the first movement, a hunting scene for the prince in the second, and the grandeur of the prince’s court.” You will hear a lot of Wagnerian harmonies and chromatic surging, and it’s probably very personal. Shortly before Zemlinsky started to work on “The Mermaid,” Alma Schindler broke up with him and married Gustav Mahler. Maybe that’s why the work does not sound the alternate “happy ending” envisioned by Andersen, in which the mermaid’s soul does prove immortal and she ascends to the skies to join other spirits of the air. There are many more examples of mermaids in Classical Music; which ones are your favourite?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter