A new life of Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805) has been published by Kahn & Averill in London. Babette Kaiserkern’s Luigi Boccherini: Musica Amorosa gives us a new and complete life of an extremely talented composer whose music has been neglected for centuries. The music we know as his is rarely in the form that he wrote it and it is only now, nearly 220 years after his death that a reassessment of his life and career is being done. His decisions about patrons and where he worked limited his ability to become the same kind of household name that so many of his contemporaries, such as Haydn and Mozart, have become. Now, with new research, we can reassess his position, his creations, and his life.

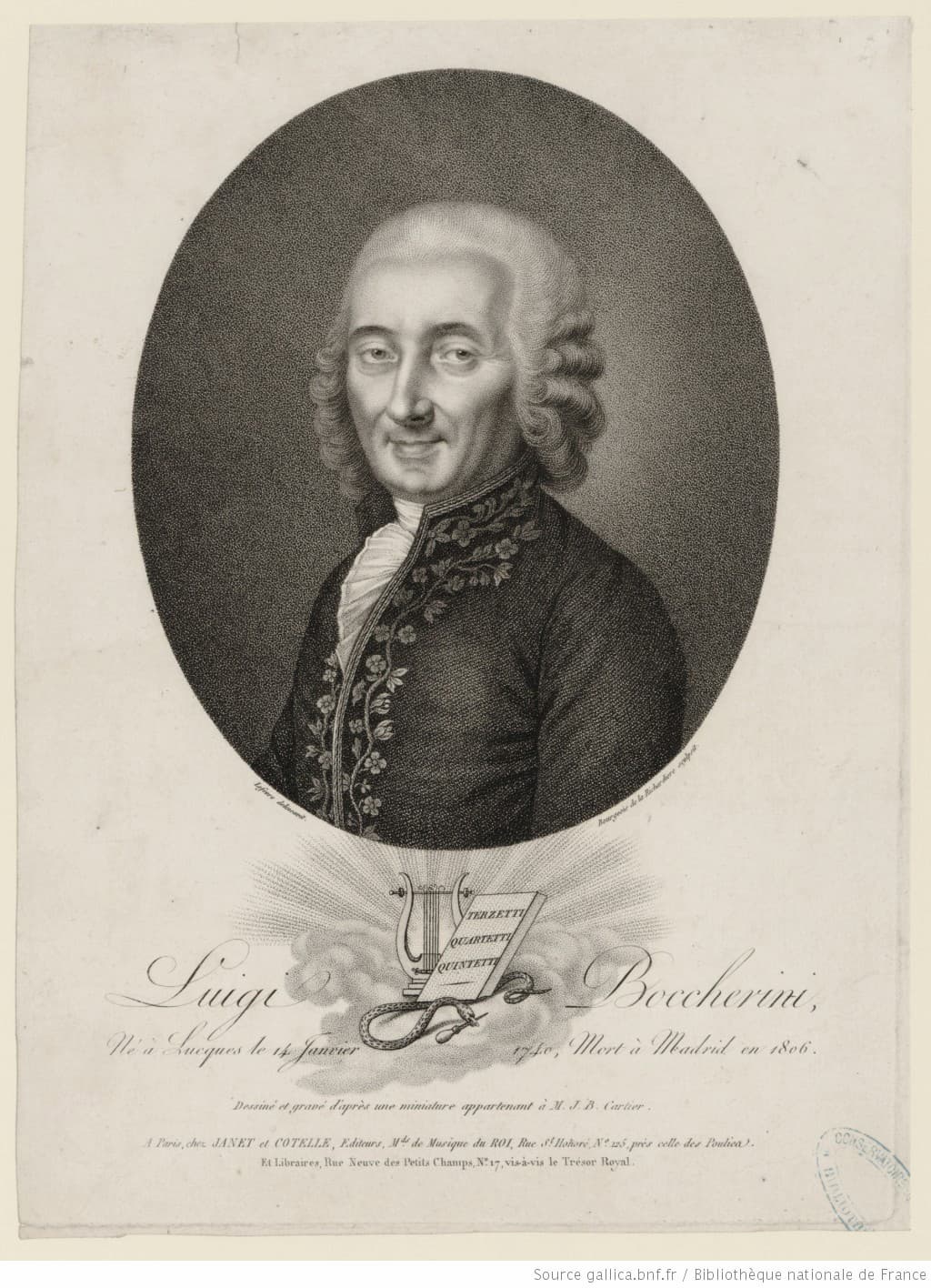

Antoine Bourgeois de La Richardière, after Lefèvre: Luigi Boccherini, 1806 (Bibliothèque nationale)

Boccherini was born into a musical family in Lucca, Italy, and his father, both a cellist and double-bass player, did much to encourage his career. After local study, he was sent to Rome, age 11. There, he studied with Giovanni Battista Costanzi, aka ‘Giovannino del Violoncello’, a gifted cellist, composer, and music director of the Cappella Giulia at the Vatican. Boccherini was studying with one of the most creative composers of the day, in a city that balanced traditional music with the latest in compositional developments: the concertato style was becoming popular as was a cantabile style in instrumental music. Church music showed the influence of the concertato style and one writer noted: ‘The sinfonia that is always played after the three evening psalms often ends with a minuet and there is no difference between church music and incidental music.’

Boccherini returned to Lucca after his two years of study and made his debut in 1756, age 13, with one of his own cello concertos. His father played double bass in the orchestra, and the conductor was Giacomo Puccini, great-great-grandfather to another Giacomo Puccini who made his name in the opera business.

Luigi Boccherini: Cello Sonata in G Major, G. 5 – II. Allegro (Josep Bassal, cello; Wolfgang Lehner, cello)

In 1757, when he was 14, he and his father went to Vienna to be musicians in the Theater am Kärtnertor; they joined the company of the Burgtheater after the Kärtnertor burned down in 1763. This was fortunate because Gluck was in charge of the Burgtheater and developing his new reform opera: no dance, simpler stories, with veracity and authenticity to the fore, and inventing the new style of ‘narrative ballet.’ Thus between Rome, where he learned the new instrumental music styles, and Vienna, where he learned the new opera and ballet styles, Boccherini was already at the forefront of musical creativity in Europe.

Luigi was not the only member of the Boccherini family to have a performing career. His eldest sister, Maria Esther, was a prima ballerina, and solo dancer at the Burgtheater, and his older brother Giovanni Gastone started in music with him but eventually found his career in writing for the theatre, creating libretti for Salieri, Paisiello, Haydn, and others.

In 1768, Luigi made his move to Spain, appearing as a solo cellist in a production in Aranjuez; by 1770, he was composer, director of music, and cellist to Don Luis de Borbón, Infant of Spain. Boccherini had come to Spain while on his way to London, but never left. Spain had been a magnet for Italian artists, craftsmen, and musicians. The castrato Farinelli was a personal servant of King Felipe V, and, in addition to the requirement of singing the same 6 arias every night (for 10 years!) to lull the King to sleep, he also bought Italian opera to Spain and made the Teatro del Buen Retiro in Madrid one of the leading opera houses in Europe. It was a house of Italian opera, usually to a libretto by Metastasio.

With the new king, Carlos III, all this changed. In 1759, Farinelli was sent back to Italy, lavish opera productions were curtailed, and French tragedies and Italian comedies took the stage replacing Metastasio’s opera seria with Goldoni’s buffo libretti. The latest music by Haydn and Boccherini became popular in Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia. With all the Italian musicians around, Boccherini fought to find a place, writing music for special occasions, dedicating music to those in power, and making his own appearances as a performer. Boccherini married Clementina Pelliccia, a soprano from Rome, and his widowed mother moved from Lucca to a small village by Aranjuez. Boccherini became part of the court retinue in Aranjuez and also had an apartment in Madrid.

Anton Raphael Mengs: Don Luis de Borbón, 1769

The Spanish royal family moved from palace to palace through the year – only Christmas, Easter, and some weeks in July were spent in Madrid. He was working for the Infante Don Luis, younger brother of the king and who was part of the retinue that travelled around Spain following the king.

Boccherini formed a string quintet with other members of the court chapel and this was the genre that Boccherini was to make his own.

Luigi Boccherini: String Quintet No. 23 in D Major, Op. 62, No. 5, G. 401 – III. Allegro assai (Ulrich Knorzer, viola; Petersen Quartet)

Starting in 1771, Boccherini composed exclusively for Don Luis de Borbón y Farnesio (1727-1785) and was one of the highest-paid in the Infante’s retinue. In addition to music, the Infante invested his substantial wealth in art, colling works by Bayeu, Breughel, Mengs, Murillo, Luis Paret, Francisco de Goya, Rembrandt, Velazquez and others. He had a substantial library of books and scores, not only by Boccherini but also by Haydn and other contemporary composers. His particular interest was his coin collection.

Unfortunately, Don Luis, who was a wealthy bachelor at court, fell afoul of the King, his older brother, because of his numerous love affairs. Don Luis was the only son in the family who had been born in Spain and so was the only one truly qualified to be king, a qualification that had been set aside when Carlos III took the throne. Afraid of a new line having a dynastic claim on his throne, Carlos III made a law specifically banning Don Luis from marrying any of his non-royal paramours without suffering ‘the loss of all titles and rights for both partners and the descendants of their union. This meant banishment from the court for the Infante, his family, his attendants, and employees. Their descendants were not even permitted to bear the royal name of Bourbon’. Don Luis, age 50, requested approval in 1776 for his marriage to María Teresa de Vallabriga y Rozas, a 17-year-old minor aristocrat without title and it was approved. With that approval came the Don Luis’ banishment to the town of Arenas de San Pedro and Boccherini with him.

Arenas de San Pedro was located some 130 km to the west of Madrid, which in 1770s Spain meant a two- to three-day journey from the capital. The marriage with his young bride was not a success – the house was in disorder and she was known to insult Don Luis beyond the ‘bounds of civility and good breeding’. Their three daughters were forbidden to go to Madrid.

Francisco de Goya: La familia del infante don Luis de Borbón, 1784. The figure on the right in the red coat is Boccherini; Goya is the painter on the left

1785 was a terrible year for Boccherini. His wife died at age 36, leaving him with 6 children; Don Luis died 5 months later, forcing Boccherini to write letters to the king requesting assistance. In response, he was promised (although never achieved) the position of first cellist in the Royal Chapel and an annual payment of 12,000 reales per year. This was unexpected, but under Don Luis, he had been making 30,000 reales a year.

In 1786, following the king’s quick response, two other good things happened to Boccherini: the Prussian Crown Prince, Frederick William II, made Boccherini his chamber composer and Boccherini entered the service of the Countess-Duchess of Benavente-Osuna in Madrid.

His agreement with the Prussian king effectively kept his music off the market for the decade between 1786 and 1796. He wrote 110 works for the king and the king collected Boccherini’s works on his own, with some 277 in his library. The manuscript works show extensive and careful notations by Boccherini about dynamics, and developing an individual system of notation to convey performance instructions. Even details on bow technique are included. With the death of Frederick William II in 1787, his son and heir to the throne, Frederick William III, Boccherini was dismissed and all payments to him ceased.

The Benavente-Osuna family had been important supporters of Madrid’s three theatres and their opera and zarzuela companies. The Countess-Duchess Maria Josefa was interested in instrumental music. In 1783, she signed a long-term contract with Haydn to secure her the rights to all his new work. He was to send her 12 new works a year of instrumental music, from quartets to symphonies, although he also sent two masses and an opera. Maria Josefa wasn’t happy and wanted him to send quartets for a mixed wind and string ensemble but he replied that he rarely used wind instruments and the results would not be satisfactory. In addition to Haydn’s works, the Countess-Duchess also owned scores by Ignaz Pleyel, Carl Stamitz, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Leopold Kozeluch, and Franz Xaver Aspelmeyer.

Her orchestra, founded in 1781, was the best in Madrid, and from 1786 to 1789, her concertmaster was Luigi Boccherini.

By staying out of the commercial music market during 1786–97, when his works were committed to his two patrons, Boccherini’s works, particularly his symphonic works, did not enter the mainstream repertoire. He also did not hear his works performed. His work is sometimes dismissed as being ‘pre-Classical’ or ‘Rococo’, while in fact, he was a contemporary of Haydn and Mozart. Written without timpani or trumpets, his symphonies are characteristically warm and soft.

Luigi Boccherini: Symphony No. 13 in C Major, Op. 37, No. 1, G. 515 – IV. Finale: Allegro vivo assai (New Berlin Chamber Orchestra; Michael Erxleben, cond.)

After being out of the spotlight for decades, first in employment with Don Luis and then with his private contracts with Prussia and the Benavente-Osuna family, Boccherini had to bring his name back to the public in his last year. He had to find new patrons, new publishers, work in new musical genres, and learn how to write to order, rather than to his own imagination, as he had been doing for decades. Some of his innovations include the pioneering piano quintets, Opp. 56 and 57 (1797 and 1799). This genre would not come into its own until the mid-19th century. A work such as the piano quintet in A minor Op. 56/6, G. 412, is hypothesized by the author as being both Boccherini’s farewell to Frederick William II and an offering to Frederick William III, an offer that was decisively declined.

Luigi Boccherini: Piano Quintet in A Minor, Op. 56, No. 6, G. 412 – V. Allegro ma non presto (Galimathias Musicum)

In his final years, Boccherini also took up interest in works for the guitar, which might be considered the Spanish national instrument. He wrote guitar quintets at the same time he was writing his piano quintets and some of the piano quintets also exist as guitar quintets, with the guitar quintets being written first.

Luigi Boccherini: Guitar Quintet No. 1 in D Minor, G. 445 – II. Cantabile (Jean-Pierre Jumez, guitar; Dimov String Quartet)

Luigi Boccherini: Boccherini: Piano Quintet in D Minor, Op. 57, No. 4, G. 416 – II. Largo cantabile (Ensemble Claviere)

Pompeo Batoni: Boccherini playing the cello, ca. 1764–1767 (National Gallery, Victoria)

In an interesting section of the price on the body from cello playing in the 18th century, Kaiserkern gives us the details of an analysis done on the composer’s body in 1995 by the University of Pisa. Boccherini was slight, only 1.65m (5’5”). The cello, as shown in the Batoni portrait, was held on bent legs. ‘The upper third of both shins was deformed by constantly gripping the instrument between his legs. The two halves of the body are subject to different stresses when playing the cello and the left side of his body was more affected, causing a distortion of the vertebrae from his neck to the sacral bone at the base of his spine’. His bow hand showed advanced arthritis, particularly at the base of his thumb and he had ‘tennis elbow’, a chronic inflammation of his left elbow.

As a player, Boccherini was recognized as making a significant contribution to the modern cello. The first cello is credited to the Cremona luthier Andera Amati in 1566 and the instrument quickly became popular, eventually pushing out the viola da gamba not only for playing basso continuo but also for solos. Boccherini, after being ignored for so long, is starting to re-engage our attention again and Kaiserkern’s book will go a long way to giving us the background we need.

Her book sets the stage and develops a thorough background of Boccherini and his time. Her analysis of the music is clear and thoughtful and gives a real insight into Boccherini’s innovations and virtuosic touch.

Babette Kaiserkern: Luigi Boccherini: Musica Amorosa. London: Kahn & Averill. 2022. 978-0-9957574-6-2.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Fascinating information about the life of Boccherini and the specifics of his personal and professional trials and tribulations. The struggles of musicians and composers have not changed much over the years, but the need for a musician to produce does not. I appreciate the detail of this description of Boccherini, his incredible talent and his connection with Mozart and Haydn. Thank you for a beautifully written dialogue.

My father Richard Olof Been was considered one of the Boccherini experts during his latter life. We owned one of the 3 sets of pressed string quintet sets, now I wonder if it was quintets. I am a classical pianist, although played violin/cello, not an expert in Luigi. All of my father’s music was left to a Boccherini foundation in Marin, Burke Schuchmann (cello) would still know of its where abouts).

We hoped he would write a book, but the computer proved just too much to learn after he retired.

I remember being told that Luigi was a virtuoso along the lines of Paganini and could play the violin parts on the cello. It is good to see people interested in him. David Brin (Marin) and Elizebeth Morrison (USC) know more