The bassoon, the bass of the woodwind instruments, is also the tenor and sometimes the alto and soprano of the woodwind instruments. Its range when extended by its larger neighbor, the contrabassoon, permits it to double and reinforce all parts of the orchestra.

Its predecessor, the dulcian (or the fagot/fagott, the curtal, the tarot, the sztort) was a one-piece instrument made of wood. The modern bassoon is made of four pieces. The French name of ‘fagot’ comes from its wooden source – a fagot (or faggot in English) is a bundle of wood. Now, the word ‘dulcian’ is used in all languages to refer to this early version.

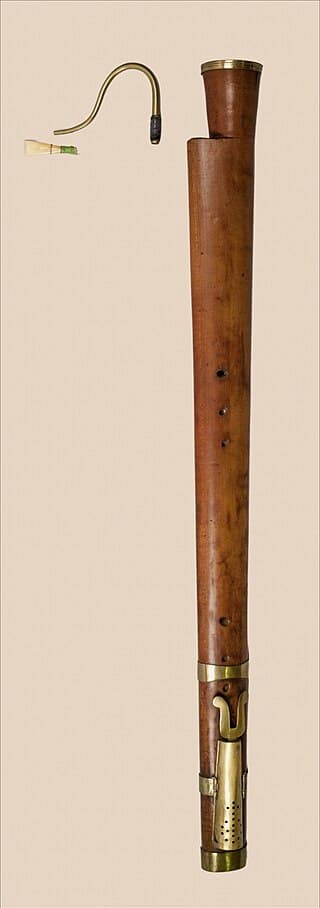

Dulcian, 1700 (Barcelona: Museu de la Música)

As you can see from the picture, the instrument had two parallel bores, connected at the bottom of the tubes. The unusual (and hidden) turn at the bottom forms the hairpin shape it still retains today. The dulcian had fingerholes like a recorder and then a split key at the bottom for the extended holes the fingers alone couldn’t reach. It is played with a double reed, like an oboe, and the reed is held away from the body of the instrument with a metal crook (the bocal). If needed, the instrument could be muted, with a separate mute put into the bell. As you can see on this instrument, the bell is flared (the modern bassoon does not have this flare). Sometimes the outside of the instrument was covered with leather (like the similar wooden cornetto).

It was the orchestral demands of the 19th century that extended the range of the humble dulcian to the orchestral bassoon. Some of the factors were: composers’ demands for improved technique, expression, and an extended range; more bassoon virtuoso composers; larger orchestras and performance places requiring louder instruments; and, importantly, the competition between instrument makers.

From one-key dulcian to three key bassoon to four keys to seven keys and then to 30 keys, the instrument grew.

three-key to 30-key Boehm system instruments

Some experiments on the bassoon, such as making it in metal, failed because the instrument lost its characteristic tone. In the modern bassoon, there are still two different key systems: the German system, developed by Wilhelm Heckel, and the French system, developed by Buffet-Crampon.

The Heckel bassoon on the left and the Buffet-Crampon bassoon on the right

The Heckel system is the one more commonly used today.

The repertoire for the bassoon dates back to the Baroque era, with Vivaldi writing 39 bassoon concertos, 37 of which have survived complete. That number is extraordinary and there’s no explanation for it – he would have been writing for the orphan girls at the Pietà. In the baroque orchestra, the bassoon would be called for, but the part not written out as it would follow the bass line played by the cello, double bass, and continuo.

Antonio Vivaldi: Bassoon Concerto in C Major, RV 476 – I. Allegro (Tamas Benkocs, bassoon; Nicolaus Esterházy Sinfonia; Béla Drahos, cond.)

In the Classical period, Mozart, his pupil Hummel, J.C. Bach, and many others contributed to the bassoon concerto tradition.

Mozart’s early contribution, his Bassoon Concerto in B flat major, K. 191, was composed in Salzburg in 1774. Of the five bassoon concertos he composed at this time, this is the only one that survives. Even at age 18, Mozart seems to be aware of what the instrument could do.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Bassoon Concerto in B-Flat Major, K. 191 – I. Allegro (Jaakko Luoma, bassoon; Tapiola Sinfonietta; Janne Nisonen, cond.)

When we listen to his student’s concerto, written around 1811, after he’d taken the position of deputy Kapellmeister at the Esterhàzy court assisting Haydn in 1804, we can hear his awareness of the development of the instrument. It had a larger range, the tone was mellower, and the dynamic range was also extended. Hummel’s requirements of the player includes ‘long, florid passages with large leaps, often in fast tempo, between high and low register’.

Hummel: Bassoon Concerto in F Major, WoO 23, S63 – I. Allegro moderato (Karen Geoghegan, bassoon; Opera North Orchestra; Benjamin Wallfisch, cond.)

In the Romantic era, one work that took the composer’s own instrument, the bassoon, and used it as an object of fun in this comic polka was Julius Fučik’s Der alte Brummbar (The Old Grumbler), Op. 210. At the very end, the composer challenges the performer with rapid virtuoso passagework.

Julius Fučík: Der alte Brummbar (The Old Grumbler), Op. 210 (David Hubbard, bassoon; Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Edward Elgar’s Romance for Bassoon and Orchestra, Op. 62, was written in 1909–1910 for the bassoonist of the London Symphony Orchestra, Edwin F. James. The work emphasizes the lyrical qualities of the instrument and it should not be forgotten that the bassoon was also Elgar’s instrument as a youth.

Edward Elgar: Romance, Op. 62 (Graham Salvage, bassoon; Hallé Orchestra; Mark Elder, cond.)

In the 20th century, composers from Berio to Boulez, Poulenc to Strauss, and Tansman to Zwilich wrote for the instrument.

Luciano Berio’s Sequenza works, written over 34 years of his life, extended the technical demands on so many instruments. Sequenza XII, written in 1995 for bassoonist Pascal Gallois, is a detailed examination of the instrument’s range. Because of the instrument’s wide range (mentioned above), Berio’s ‘meditation’ on its possibilities gives us a portait of the bassoon as both a soulful and humorous instrument.

Luciano Berio: Sequenza XII (Kenneth Munday, bassoon)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich takes the opposite point of view of the bassoon, Her Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra, written in 1992 for bassoonist Nancy Goeres, who gave the premiere of the work with the Pittsburgh Symphony under Lorin Maazel, takes the instrument very seriously. It’s not the comic instrument that others made it but is set within a ‘brooding and intense’ orchestration.

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Bassoon Concerto (arr. T. Hill for bassoon and wind ensemble) – I. Maestoso (Renee H. DeBoer, bassoon; The United States Navy Band; Kenneth C. Collins, cond.)

An ultra-modern work for the lowest bassoon, the contrabassoon, required not only technical perfection on the part of the player, but that, in fact, an entirely new instrument that was capable of playing the range required by the composer. Kalevi Aho’s Concerto for Contrabassoon and Orchestra (2004–2005) was written for bassoonist Lewis Lipnick and received its premiere in 2006 with Lipnick and the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Litton. Where the first movement of the concerto explores the lowest register of the instrument, the Presto second movement explores the contrabassoon’s technical agility.

Kalevi Aho: Contrabassoon Concerto: II. Presto (Lipnick Lewis, contrabassoon; Bergen Philharmonc Orchestra; Andrew Litton, cond.)

The one work we’ve skipped here isn’t specifically for bassoon, but the bassoon part in it was so radical for its time that it must be discussed.

The opening of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913) puzzled everyone with its sound—guesses were made that it was an oboe, a muted trumpet, or a clarinet—but it was the bassoon in an unusual range. Words were even made up for the melody: ‘I’m a bassoon, I’m not an English horn, this part is much too high for me….’

Igor Stravinsky: Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) – Part I: Adoration of the Earth: Introduction — (Orchestre de Paris; Klaus Mäkelä, cond.)

The source for Stravinsky’s melody was the Lithuanian folk song ‘Tu, manu seserėlė’ (Oh My Sister), which Stravinsky changes with additional rhythms and added grace notes. As Stravinsky’s idea was that the opening should ‘represent the awakening of nature, the scratching, gnawing, wiggling of birds and beasts’, the bassoon’s sound emphasizes the imagery. The bassoon sound at the beginning of this groundbreaking ballet remains one of the most remarkable openings today.

The Rite of Spring/Tu mano seserėle

The bassoon can be comic or warm, supportive or solo, or even mysterious. It’s agile and yet can be the most stable of bases. Despite the addition of dozens of keys to its basic form, it retains the warm sound that composers loved.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter