One of the strangest stories in the recent history of classical music is that of the reception of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. It is a truly astonishing story of the kind that had not occurred before – and has not occurred since. In much of what follows, I will draw on the convincing and highly detailed 1998 article by Luke B. Howard for The Musical Quarterly.

Henryk Górecki © Wikipedia

Throughout the 1960s, Polish composer Henryk Górecki composed critically acclaimed, highly avant-garde works. His Scontri impressed Stockhausen and Nono and premiered unpitched string clusters before Penderecki’s Threnody at the 1960 Warsaw Autumn, and his serialist First Symphony received the top award at the second Paris Youth Biennale in 1961 and was performed at Darmstadt in 1963. However, in the 1970s, he slowly withdrew from modernist and avant-garde circles and began to explore new musical arenas: modality, large slow gestures, motivic repetition, and simplicity. He extracted himself so quietly that, according to Luke B. Howard, “few noticed his absence.” Instead, it was his fellow nationals who saw his transformation; Adolf Dygacz, collector of folk songs, passed many melodies on to the interested Górecki. Polish critics witnessed the influence of Karol Szymanowski and Andrzej Nikodemowicz, Polish folksong, and the culture of rural Catholicism in his artistic development.

Fast forward to April 1977: the International Festival of Contemporary Art and Music in Royan, one of the cornerstone avant-garde music festivals at the time. Górecki returns with his Third Symphony, his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, composed between October and December 1976 and commissioned by the South-West German Radio Orchestra, Baden-Baden. The work had been long in gestation: Górecki found the text for the second movement in 1970 and mentioned working on a symphony of lamentation to a friend in 1974. The work represented a kind of unveiling to a wider audience of all of the thinking, development, and exploration he had been doing in the 1970s and focused on themes incredibly important to his life history – this we will come to later.

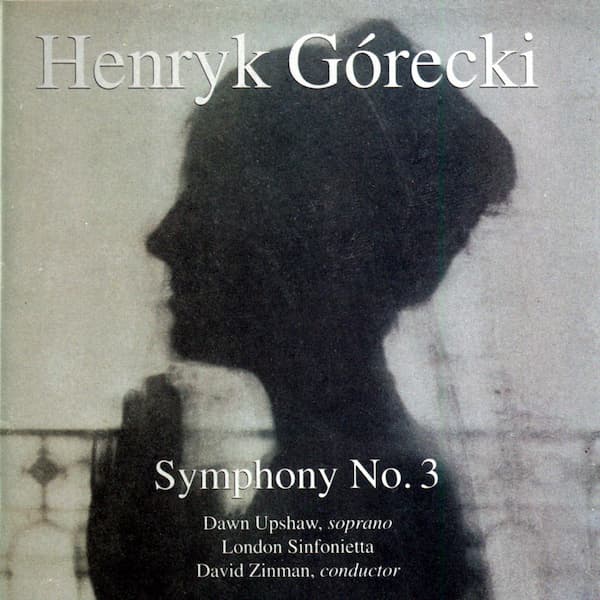

Henryk Mikołaj Górecki: Symphony No. 3, Op. 36, “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs” – II. Lento e largo – Tranquillissimo (Dawn Upshaw, soprano; London Sinfonietta; David Zinman, cond.)

At the premiere in Royan, the Third Symphony was almost universally derided. Heins Koch, writing for Musica, opined that the symphony “drags through three old folk melodies for an endless 55 minutes.” Other critics called the work “decadent trash… encircling the true pinnacles of avant-gardism,” a “non-composition,” an instance of “childish ‘new simplicity’.” One “prominent French musician” uttered a loud profanity during the close of the third movement. The symphony was rejected: it was deemed to lack the true virtues of avant-gardism: complexity, cutting-edge innovation, difficulty, virtuosity, a pioneering and radical spirit. Górecki disagreed: “for me, it was the most avant-garde piece I heard there.”

If asked now to predict the fate of the Third Symphony in the subsequent decades, you would be forgiven for thinking that the work flopped and died an unceremonious death. If you hedged your bets and predicted that it continued to be performed sporadically by predominantly Polish groups, that would be a sensible guess, too. What actually happened can be considered permanent proof of the adage used by Lord Byron in his 1823 Don Juan:

Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips, c. 1813 © Wikipedia

“Tis strange – but true; for truth is always strange;

Stranger than fiction;”

The Third Symphony continued to live a modest public life. In 1978, the Polskie Nagrania recorded the symphony with soprano Stefania Woytowicz and released it in Poland. In 1982 it was re-recorded and distributed across Western Europe and the United States. It was a bizarre event in popular culture that slowly began to give the symphony exposure outside of those already interested in new music or Górecki. Entirely without Górecki’s knowledge or permission, French director Maurice Pialat stuck part of the symphony – the Holy Cross Lament section from the first movement – over the credits of his film about drugs, corruption, and the police starring Gerard Depardieu and Sophie Marceau. That fragment alone smuggled into the credits of the only modestly successful film, Police, generated so much interest and excitement that the record label Erato released the complete symphony on LP the following year. However, they bungled this by calling the LP a “soundtrack” of the film and giving no information about the composer. Still, with this exposure, the symphony had gained support from the editor of the American Record Guide, Donald Vroon, and Dieter Hueler, general manager of record label Koch-Schwann, and as such, it was re-reviewed with great praise, and re-released by British label Olympia. In the 1980s, excerpts from the Schwann recording of Górecki’s Symphony featured in the industrial protest music of the working-class industrial-rock group Test Department. The serene, mournful music of the symphony was contrasted with displays of gas cylinders and corrugated iron, collages of lights, images, and musique trouvé, and instruments foraged from garbage dumps and factory refuse piles. The use of the symphony was tied to Górecki’s Polish identity, a kind of underground allusion to Poland’s Solidarity movement of the 1980s as a symbol for the oppression and revolt of the working class.

At this point, we can introduce three key players in the final stages of the Third Symphony’s skyrocketing ascent to fame. David Drew, director of the publishing firm Boosey and Hawkes, legitimised Górecki’s reputation as a composer in the U.K. by granting him a publishing contract in 1987. As such, orchestras in the U.K. began to reperform the symphony, and at one fateful performance by the London Sinfonietta, our second key player, Bob Hurwitz, senior vice-president of Elektra-Nonesuch records, sat in the audience and decided that the symphony deserved re-recording. Finally, we meet Dawn Upshaw, Grammy-award winning soprano, beloved for her musical talent and public image as a kind, innocent, and deserving individual. The decision to re-record with Upshaw instead of Stefania Woytowicz, who sang in a heavier, more dramatic style, combined Upshaw’s celebrity and name recognition with the opportunity to showcase a gentle and angelic vocal interpretation that perfectly reflected the concepts and atmospheres of eternal femininity, innocence, and motherhood of the Third Symphony.

The London Sinfonietta recording with Dawn Upshaw was released in 1992. Richard Morrison of the London Times quipped about the release: “What more certain recipe for financial ruin than to release a recording of a symphony by a Polish composer so obscure that he was not even famous in Poland.” Morrison was wrong. The recording soared to unprecedented levels of popularity, unheard of for classical records. Classic FM regularly broadcasted the Symphony to its 5 million weekly listeners in the U.K. from September 1992 onwards; in the U.S. the record climbed into Billboard’s top ten and stayed there. By 1993 the symphony had outsold new albums by Michael Jackson and Madonna. Within two years, over 700,000 copies had been sold worldwide, and to date, over one million – making the Elektra-Nonesuch recording of Henryk Górecki’s Third Symphony arguably the best-selling contemporary classical record of all time, far outselling any single recording of a work by Debussy, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Bach, or Mozart.

English National Opera’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs: 2023 Production © eno.org

With the labyrinthian, epic story of the Third Symphony’s many adventures behind us, some questions remain. What is this symphony – what is it about, conceptually and musically? Who is this Polish composer, really? Why were so many influential figures such staunch advocates of this work, ultimately guiding it to commercial success?

And above all, how can we make sense of one of the most unusual receptions of a work in the history of classical music?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I wept the first time I heard the 3Rd…I felt it touch my soul and I still listen to it..often around 2 or 3 am alone, with the headphones. I never want to be disturbed when I listen to Dawn Upshaw’s heartbreaking rendition of the music..I’m weeping now,,,( Stendahl syndrome overcomes me) Surely the saddest music ever written.