Johannes Brahms may have had a prickly personality, but he was also deeply admired by quite a few colleagues. Many of them expressed that admiration by dedicating works to Brahms.

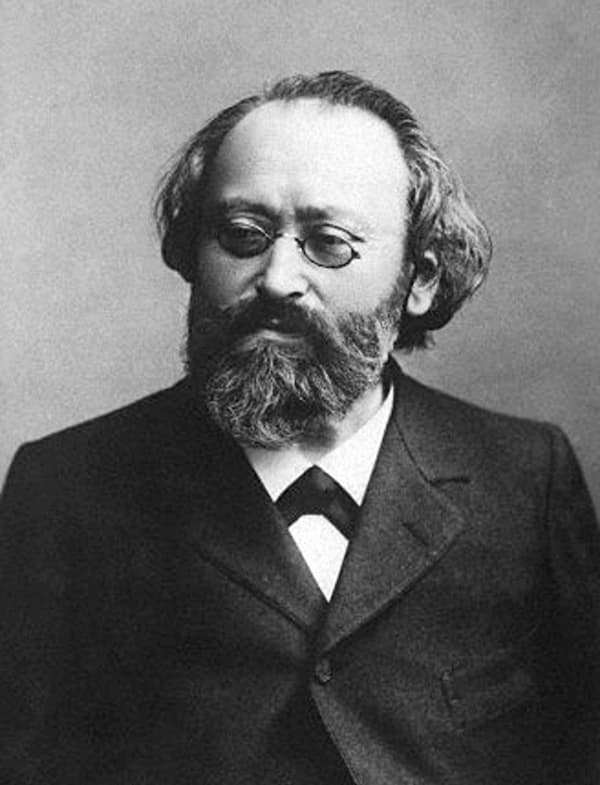

Johannes Brahms, 1880

Today, we’re looking at seven of the most interesting examples of music dedicated to Brahms…and in the process, shedding light on some of the most meaningful friendships in Brahms’s life.

Joseph Joachim: Violin Concerto No.2, Op.11 (1857)

Joseph Joachim was born in 1831 in the town of Köpcsény in the Kingdom of Hungary.

When he was five, he began studying the violin. He proved to be a child prodigy and went on to study in Vienna and Leipzig.

As a young man, Joachim became associated with Franz Liszt and his circle, but he soon became disenchanted by the entire scene. In 1857, when he was in his mid-twenties, he wrote Liszt bluntly, “I am completely out of sympathy with your music; it contradicts everything which from early youth I have taken as mental nourishment from the spirit of our great masters.”

Joseph Joachim (Photo by Julius Allgeyer

In 1853, Joachim met Robert and Clara Schumann when Joachim performed at the Lower Rhine Music Festival.

That same year, he also met Johannes Brahms, an ambitious twenty-year-old composer and pianist.

Joachim connected Brahms with the Schumanns, and the meeting proved life-changing for all of them. Together, the group became the core of a musical movement that would be highly influential in nineteenth-century classical music history…and challenge the philosophy of Liszt and his son-in-law Wagner.

The late 1850s were productive years for Joachim. While Joachim wrote his own second violin concerto “in the Hungarian style”, he was also in intense contact with Brahms about Brahms’s first piano concerto.

As a tribute to their friendship and creative partnership, Joachim dedicated his second violin concerto to Brahms.

Max Bruch: Symphony No.1, Op.28 (1868)

Max Bruch was born in 1838 in Cologne. He started composing at the age of nine and formally studying music at eleven. He had a very successful career and wrote over a hundred works.

Bruch and Brahms met at the Lower Rhine Music Festival in 1868. That year Bruch proposed dedicating his first symphony to Brahms, who accepted. (That said, Brahms would never dedicate a work to Bruch.)

Max Bruch

Brahms was a sarcastic man, and his alleged dissents against poor Bruch are legendary. Supposedly, after Bruch played a piano arrangement of his oratorio Odysseus, Brahms’s response was, “Say, where do you get your music paper? First rate!” Although he may not have been terribly impressed by it, Brahms did conduct Odysseus in 1875.

Heinrich Hofmann: Ungarische Suite, Op.16 (ca. 1873)

Composer Heinrich Hofmann was born in Berlin in 1842. Relatively little is remembered about him nowadays, but in the late nineteenth century, his 1874 Frithjof Symphony often appeared on German concert programs.

Around 1873, Hofmann published his Ungarische Suite (Hungarian Suite), which bore a dedication to Johannes Brahms. It seems likely that this suite was a tribute to Brahms’s Hungarian Dances, the first two books of which were published in 1869. If Brahms had a response to this particular dedication, it hasn’t survived.

In the mildest possible praise of Hofmann, influential critic and Brahms apostle Eduard Hanslick wrote, “Heinrich Hofmann is not a highly gifted composer, but a reliable, skilled practical musician, able to present commonplace ideas in a tastefully refined form.”

His Hungarian Suite is fascinating to compare with Brahms’s Hungarian-inspired works.

Antonín Dvořák: String Quartet No.9, Op.34 (1877)

Antonín Dvořák was born near Prague in the present-day Czech Republic in 1841. As a boy, he trained as both a violinist and composer.

Dvořák worked in relative obscurity until 1874, when he won the Austrian State Stipendium composition competition, which provided a stipend to the winning composer. Brahms was on the jury and was very impressed with Dvořák’s work.

Antonín Dvořák

Dvořák won the prize in 1876 and 1877, too. The victory was especially meaningful in 1877, as two of his young children died in August and September that year, and the devastated family was in desperate need of good news.

After that third success in 1877, Dvořák and Brahms got in touch by letter. Dvořák expressed his admiration for Brahms, and Brahms returned the admiration by introducing him to his publisher, Fritz Simrock.

Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances, loosely inspired by Brahms’s Hungarian Dances and published by Simrock in 1878, became one of the bestselling works in Simrock’s catalogue and is still often played today.

In appreciation of the recognition that Brahms gave him at a pivotal point in his life, Dvořák dedicated his ninth string quartet to Brahms.

Ferruccio Busoni: 6 Études, Op.16, BV 203 (1883)

Ferruccio Busoni was born in 1866 to two musicians in Tuscany. He had a difficult childhood as a performing child prodigy.

Ferruccio Busoni, 1913 (Photo by Varischi & Artico)

Between the ages of nine and eleven, Busoni studied in Vienna at the same time that Brahms lived in the city. Busoni returned to Vienna as a teenager, where the two met.

Busoni wrote his 6 Études in 1883, when he was seventeen. They were published three years later, which is when they were formally dedicated to Brahms.

It doesn’t seem like Brahms and Busoni’s paths crossed very often after their initial meeting, but interestingly, they did both write famous piano transcriptions of Bach’s Chaconne in D minor.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: String Quartet, Op.42 No.1 (1884)

Heinrich von Herzogenberg was born in Graz, Austria, in 1843. As a young man, he studied law, politics, and philosophy in Vienna, but he was also attracted to music.

In 1866, he married a beautiful and talented Brahms student (and crush) named Elisabeth von Stockhausen. Over the course of their marriage, the couple lived in Graz, Leipzig, and Berlin.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Herzogenberg spent much of his creative life trying to impress Brahms, who was always hesitant to give wholehearted praise to him…possibly due to personal jealousy. Brahms continued to find the kind and intelligent Elisabeth to be an invaluable sounding board.

Learn more about Brahms’s relationship with Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.

In the end, Brahms begrudgingly admitted that Herzogenberg had at least some talent. “Herzogenberg is able to do more than any of the others,” he once allowed.

In 1884, Herzogenberg officially dedicated three string quartets to Brahms, including this one in G-minor, the first of the set.

Carl Reinecke: Cello Sonata No. 3, Op. 238 (1897)

Carl Reinecke was born in 1824 in Hamburg. His father was a music teacher, and Carl began composing and performing publicly on the piano when he was just a child.

He studied with Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann and subscribed to their philosophy of music, which would later be championed by figures like Clara Schumann, Joseph Joachim, and Johannes Brahms.

Carl Reinecke, 1890

In 1860, he became music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and a teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory. Over the course of his career, he taught many of the nineteenth century’s most famous composers: Grieg, Janáček, Albéniz, Bruch, and others.

His third cello sonata was written after Brahms’s death in 1897. In it, Reinecke paid tribute both to Brahms’s style and the gravity of his death.

One journal, Musikalisches Wochenblatt, wrote:

The sonata is entirely worthy of bearing the name of the master to whose memory it is dedicated, Johannes Brahms. Its atmospherically charged ideas make its three movements music of noble character and solid construction. The tonal impression made is excellent.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter