Johann Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825), much better known under his penname “Jean Paul,” was one of the most prolific and prominent writers of his generation. Owing to the structural and linguistic idiosyncrasies of his writings, he was heavily criticized in his lifetime, but some literary critics considered him “one of Germany’s literary greats, a force to rival Goethe and Schiller.”

Johann Paul Friedrich Richter

According to scholars, “Jean Paul cultivated one of the most unusual styles in German writing, its chief characteristics including extravagant metaphors, puns, and wordplay, syntactic convolutions, the juxtaposition of high-flown poetry and homely prose, and humorous or sentimental digressions which could range from discussions of Fichtean philosophy to hot-air ballooning.” Jean Paul published his first major novel in 1793 under his pseudonym, and he almost instantly rose to literary fame. Over the course of the next decade, he wrote four more novels, all long and complicated works with contemporary cultural and intellectual allusions, which were some of the most widely read books in the early nineteenth century.

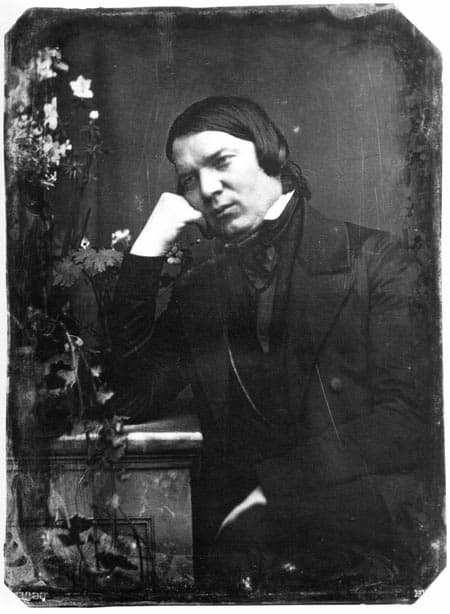

Jean Paul and Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann, 1850

During his time as a theology student at the University of Leipzig, Jean Paul developed a distinct interest in music. Apparently, he much enjoyed the symphonies and oratorios by Joseph Haydn, the church music of Graun and Hasse, and the operas of Mozart, Gluck, and Méhul. As such, it is not surprising that music plays a significant role in Jean Paul’s fictional and theoretical works. For one, Jean Paul re-creates his personal musical experiences. But more importantly, his musical aesthetic “prefigures the whole array of ideas associated with the early romantic aesthetic whereby music was viewed as an entry into a metaphysical dream world, an expression of infinite longing, and a language capable of uttering the unutterable.” The young Robert Schumann was strongly captivated by Jean Paul’s idiosyncratic style and language. In fact, in his early prose fiction, he happily imitated the writing style of his literary idol. He writes, “were I a smile I would play about her eyes; were I a spirit of joy I would gently course through her veins; yes, and were I a tear I would weep with her, and when she smiled again gladly melt away on her eyelashes and die, gladly cease to be.”

Robert Schumann: Papillons, Op. 2

Schumann equated Jean Paul with the genius of Shakespeare, Beethoven, Schubert, and Bach. But Schumann was also more specific, as he understood that “Jean Paul is all the time portraying himself in the form of two persons. He is Albano and Schoppe, Siebenkas and Leibgeber, Vult and Walt… Only a Jean Paul could have combined in himself such opposite characters. The contrasts are very harsh sometimes, not to say extreme.” Schumann then adds, “I often asked myself what would have become of me if I had never known Jean Paul. In one respect, at any rate, he seems to have an affinity with me, for I foresaw him. Perhaps I would have written some kind of poetry, but I would have withdrawn myself less from other people and dreamt less. I cannot decide, really, what would have become of me, the problem is impossible to work out.” There can be no doubt, however, that “Florestan” and “Eusebius,” the principal crusaders against music philistinism and the conflicting parts of Schumann’s own personality, are modeled “on such antithetically paired characters as “Walt” and “Vult” in Jean Paul’s novels Flegeljahre (The Awkward Years).

Robert Schumann: Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6

Deeply under the influence of Jean Paul, Schumann composed the chain of miniature dances he subsequently titled Papillons. As Schumann writes, “Schubert is still my only Schubert, especially as he has everything in common with my only Jean Paul. When I play Schubert, I feel as if I were reading a novel by Jean Paul set to music.” Schumann later explained to his editors, “I am permitting myself to add a few words about how the Papillons arose, as the thread that binds them to each other is almost invisible. You remember the last scene in Flegeljahre—masked ball—Walt—Vult—masks—Wina—Vult’s dancing—the exchange of masks—confessions—anger—revelation—the hurrying away—the closing dream and then the departing brother? I often turned to the last page, for the ending seemed to me no more than a new beginning—almost unconsciously I was at the piano, and so one Papillon after another came into being.” In his personal copy of the novel, Schumann provides annotations that link the various episodes to individual numbers of his music.

Robert Schumann: Blumenstück, Op. 19 (Freddy Kempf, piano)

Robert Schumann traveled to Vienna in 1838 in hopes of publishing his music journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, in that city. Once established, Clara would follow him to Vienna and finally escape the clutches of her father. However, his hopes were quickly dashed. He did make a number of important friendships and immersed himself in Vienna’s rich concert life. However, he failed to make much of an impression, as the Austrian censors demanded that Schumann take on Austrian citizenship to be allowed to publish his periodical in Vienna. In addition, he found “Vienna a very unpromising environment for this musical ideas, and entirely too conservative and fickle.” As a scholar writes, “the months in Vienna, however, brought a new or seemingly new side of Schumann’s output. After almost a decade of fragmented multi-unit works, he now produced three pieces in one long movement each. These three works, the Arabeske, Blumenstück, and Humoreske, ideally mirror Schumann’s longing for a simple, contented existence. The Blumenstück, Op. 19 derives its title from Jean Paul’s novel Siebenkas (Sevencheese), subtitled by the author “Blumen-Frucht-und Dornenstücke” (Flower, Fruit, and Thorn Pieces).

Jean Paul, Judit Varga and Georg Friedrich Hass

Judit Varga: Blumenstück

The story details the life of Firmian Stanislaus Siebenkas, who is unhappily married. Desperate, he goes to consult his friend Leibgeber, who turns out to be his alter ego, or Doppelgänger. Leitgeber convinces Siebenkas to fake his own death and start a new life. Siebenkas does take the advice of his alter ago and soon meets the beautiful Natalie. They fall in love and celebrate their “wedding after death.” A literary scholar writes, “the sudden meeting of satire and touching moments in Siebenkas’ psychological pains, moves the reader to want to know about philosophical honesty as well as comfort of soul. The inconsistency and being torn apart of Siebenkas is programmatic, and still today a sign of sensitivities of bourgeois individuals.” The novel unfolds as a series of episodes, and with the designation “Blumenstück,” Jean Paul presents a digressive subsection in the novel, “one of those meditative episodes that usually has some connecting tissue in common with the main work.” Jean Paul’s literary construct, as we can hear in the featured contemporary works by Judit Varga and Georg Friedrich Hass, still enjoys currency today.

Georg Friedrich Haas: Blumenstück

Jean Paul and Stephen Heller

Stephen Heller

The French pianist and composer of Hungarian birth Stephen Heller (1813-1888) set numerous lieders to words by Goethe, Heine, and other German poets. When he submitted some compositions for criticism to Schumann, he was reviewed enthusiastically and soon became one of Schumann’s favourite “Davidsbündler.” Heller published roughly 160 piano compositions, ranging from elementary studies to demanding character pieces. Schumann accorded them high praise, remarking “the forms are new, fantastic and free, and crafted with imagination and the ability to fuse contrasting elements.” In fact, Schumann heard “Janus-like faces, looking towards both his Classical antecedents and Romanticism.” To be sure, Heller had recourse to literary reference in his music, and in 1853 he published a set of 18 lyric pieces Nuits blanches under the title “Blumen-Frucht-und Dornenstücke.” The reference to Jean Paul is unmistakable, and the pieces unfold as a series of charming and finely crafted vignettes. A scholar writes, “the whole series is a unified work, with necessary contrasts of key and feeling as it progresses, through the motor energy of the fourth piece and the calm lyricism of the fifth to a final happy ending.”

Stephen Heller: Nuits Blanche, Op. 82 (Jean Martin, piano)

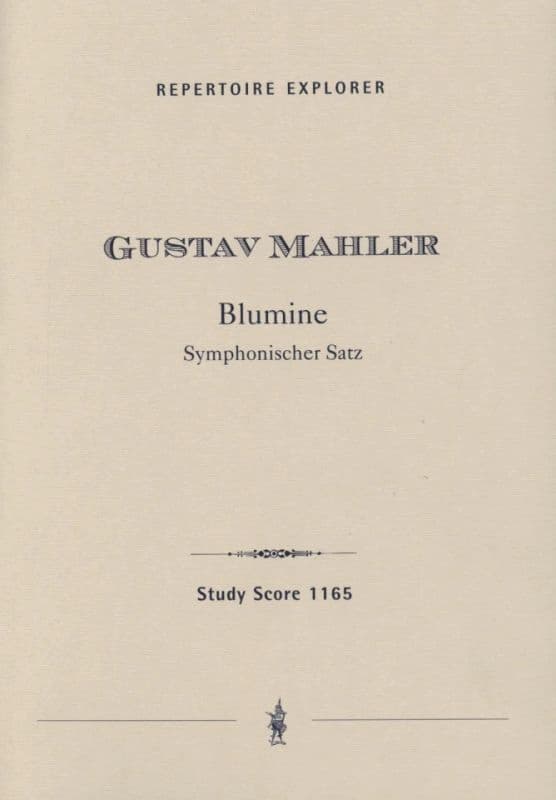

Jean Paul and Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler

Schumann’s engagement with Jean Paul is relatively well documented, but it might come as a surprise that the author also captivated Gustav Mahler. Mahler’s symphonic journey started rather ominously with the premiere performance of his First Symphony at the Hungarian Royal Opera House in Budapest on 20 November 1889. Greeted by animosity, indifference, bewilderment, and rejection, Mahler’s first symphony not only represented a highly personal and conceptual musical exploration, but it sounded in an exceedingly volatile musical environment. Mahler had initially conceived this work as a “symphonic poem in two parts,” but stunned by the severe reaction of the Budapest audience, he quickly retitled his composition “Titan, a tone poem in symphonic form.” That title originates with the four-volume novel Titan, written by Jean Paul between 1800 and 1803. The author regarded this work as his most significant literary achievement, believing it to be his most mature and tightly constructed novel. In essence, Titan is a “Bildungsroman” (coming-of age novel), that shows the development of a young man’s character towards harmony and balance.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D Major “Titan”

The novel comprises some 900 pages and tells the story of the education of the hero Albano de Cesara, his transformation from a passionate youth into a mature man who ascends the throne of the small principality of Pestitz. Jean Paul originally considered using the title “Anti-Titan” in order to “express more clearly the idea of hubris, of the inevitable doom of the “Himmelsstürmer” (Heaven-stormer) of Romanticism.” With Mahler coming of age, he appended titles to individual movements of his symphony. Audiences at performances in Hamburg and Weimar in 1893 and 1894, respectively, were treated to a descriptive program in which Mahler detailed the metaphorical content of each movement. In keeping with his references to Jean Paul, the title of the first part is taken literally from Siebenkas:

Gustav Mahler: “Blumine”

Part I: Aus den Tagen der Jugend: Blumen-, Frucht-und Dornenstücke

(Days of Youth: Flower, Fruit, and Thorn pieces)

This opening part additionally contained a section titled “Blumine” (Flower Piece).

Programmatic explanations, however, did not alleviate the continued hostile reactions this work received from audience members. After a performance with Mahler conducting, the frustrated composer confided in his wife Alma, “Sometimes it sent shivers down my spine. Damn it all, where do people keep their ears and their hearts if they can’t hear that!” Mahler continued to refine the composition, and as part of this process, the “Blumine” movement was discarded. Eventually, Mahler suppressed all titles for a performance in Berlin in 1896, expunging all programmatic explanation and newly christened the work “Symphony in D Major, for large Orchestra.” As for the “Blumine” movement, derived from the title of a collection of magazines published by Jean Paul, Mahler had originally composed the music for a set of dramatic poems by Joseph Victor von Scheffel. The “Blumine” movement was only rediscovered in 1966, and Benjamin Britten gave the first performance in 1967 after it had been lost for over seventy years. Mahler rejected the tone poem in favor of the symphony, as he explained to a friend, “You are right in saying that my music generates a program as a final imaginative elucidation, whereas with Richard Strauss the program is a set task…” Mahler might have rejected the tone poem in favor of the symphony, but he was unable to hide his youthful infatuation with Jean Paul.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter