Beethoven’s Erard Piano

It has never been a big secret, but the piano is definitely my favorite instrument. For me, no other instrument possesses that kind of versatility. Actually it’s ideal as a means of musical expression for both the amateur and the skilled professional. With a range of typically eighty-eight notes the instrument lends itself to many different musical styles, and it blends so well with almost any combination of instruments. It’s no surprise that the piano repertoire is huge. Because of the instrument’s complexity, the piano is a rather recent development.

Beethoven, 1803

While we can easily play piano repertoire from the baroque era and Johann Sebastian Bach or later by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on a modern piano, the first composer to write true piano music was Ludwig van Beethoven. He had tremendous technical ability and critics wrote, “He was attacking pianos with such force that during the performance, keys, hammers and strings would be flying.” But virtuosity is all but one aspect of Beethoven’s piano repertoire as he was able to compose music with “glowing passion, exuberance, heroism, nobility and dramatic pathos.” In today’s blog I want to explore Beethoven’s piano repertoire by casting the net a bit wider. I won’t focus exclusively on his published 32 piano sonatas, but include works that sound the participation of the instrument in chamber and concerto settings.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73

Beethoven’s autograph sketch for part of the first movement

of the Emperor Concerto © esm.rochester.edu

Why not start this blog on Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano repertoire with a bang? And it hardly gets any more majestic than Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto, nicknamed “Emperor.” Composed during the Napoleonic occupation of Vienna, Beethoven was already substantially deaf when the work premiered in 1811. At that time, it was one of the most original, effective, but also one of the most difficult concertos in the piano repertoire. Just listen to the blindingly difficult cadenza that opens the concerto. The brilliant solo piano part permeates much of the musical discourse of the composition, but Beethoven also includes an “Adagio” movement full of yearning. The piano wanders into far and distant musical galaxies, and Beethoven presents one of his most beautiful and memorable melodies. However, Beethoven always remains unpredictable and the concluding Rondo starts with a quiet introduction featuring fragments of the principle theme. Everybody understood that Beethoven never wrote for the masses, but full of proud self-reliance, wrote down what he heard in his head. Composed over 200 years ago, the “Emperor” is still one of the greatest concertos in the piano repertoire.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2 “Moonlight”

Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata © BBC Music Magazine

When we talk about beautiful and memorable Beethoven melodies, we need look no further than the opening movement of the famous “Moonlight Sonata.” Today, it’s a veritable cliché, but it is a sure staple of the piano repertoire. The famous nickname comes from a critic and poet as the music “inspired a vision of a boat on Lake Lucerne by moonlight.” Beethoven had never been to Lake Lucerne, but he did instruct the performer to use the pedal throughout the earworm opening movement. “The harmonies do become like watercolors, seamlessly blending and swimming into each other.” Beethoven was a fragmented individual full of contradictions. He struggled with a severe disability, a failing body, mental instability and an alcohol addiction. He also had highly volatile temper, and dreadful communication and social skills. How then can we explain the radiant beauty of the opening movement of the “Moonlight Sonata”? As a scholar has observed, “composing and the disciple associated with his art was for Beethoven the personal therapy that confidently anchored the sinking ship.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in D Major, Op. 70 No. 1 “Ghost”

Beethoven composing at the piano © Bettmann/Corbis

Ludwig van Beethoven greatly enriched the piano repertoire by including the instrument in his chamber music settings. Of all Beethoven’s Piano Trios, the “Ghost Trio” is probably the most famous. The Ghost Trio, named for the sonic effects of the slow movement, was written while Beethoven was staying on the estate of Countess Marie von Erdödy outside Vienna, and it is dedicated to her. The nickname actually comes from Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny, who wrote that the slow movement always reminded him of the appearance of the ghost in the Shakespeare play Macbeth. Czerny probably didn’t know that Beethoven had included in the sketchbook preliminary ideas for an opera based on Macbeth. The piano plays an integral part in the presentation and development of the musical material, and a critic writes, “Beethoven could write music whose beauty will last you all your life and he could take the driest sticks of themes and work them up so interestingly that you find something new in them at the hundredth hearing; in short, you can say of him all that you can say of the greatest pattern composers; but his diagnostic, the thing that marks him out from all the others, is his disturbing quality, his power of unsettling us and imposing his giant moods on us.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 “Appassionata”

Mayer: Ferdinand Ries, 1821

One of the most famous works in Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano repertoire was conceived in the small village of Döbling, in the Vienna Woods. Beethoven went there for long walks, sometime in the company of his student Ferdinand Ries. Ries reported that “Beethoven was humming, and more often howling, always up and down without singing any definite notes. When I questioned him to what it was, he answered, ‘a theme for the sonata [Op. 57] has occurred to me.’ Once we returned home, Beethoven ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat. I sat down in the corner and he soon forgot all about me. Finally he got up, was surprised that I was still there and said, ‘I cannot give you a lesson today, I must do some work’.” And that work referred to his f-minor sonata Op. 57, a composition commonly known as the “Appassionata.” The publisher supplied that nickname, but Beethoven did not protest. The opening movement is almost symphonic in scope, and it is certainly one of Beethoven’s greatest works in the piano repertoire.

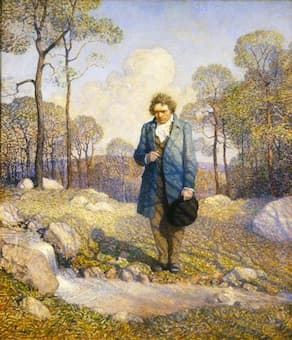

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 5 in F Major, Op. 24 “Spring”

N.C. Wyeth: Beethoven and Nature (1917) (Steinway Art Collection)

During Beethoven’s lifetime, it was still customary for instrumental sonatas with piano to be seen as a showcase for piano with an accompanying role for the other instrument. The early Beethoven violin sonatas were published with the inscription “sonatas for harpsichord or piano, with a violin.” However, as he gained more confidence in the medium Beethoven began to stress the partnership of the two instruments rather than the violin playing a chiefly accompaniment role. Only when the violin graduated to a true partner in the musical discourse did the genre begin to attract professional violinist. Yet, there is no doubt that much of the music in Beethoven’s violin sonatas is strongly driven by the keyboard. The most popular of Beethoven’s violin sonatas has earned its nickname “Spring,” on account of the vernal loveliness of the primary theme announced by the violin and echoed by the piano in the opening Allegro. A contemporary critic wrote, “This sonata is among the best Beethoven has written, which is to say that it is among the best being written at all. The composer’s original, fiery and bold spirit… becomes more and more apparent now…”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor “Für Elise” WoO 59

Ludwig van Beethoven and Therese Malfatti

For the most instantly recognized and most beloved Beethoven piece in his piano repertoire we need look no further than the Bagatelle Für Elise. We all know this delicious tune, but it’s not at all clear who was “Elise.” Apparently, Beethoven, already 40 years of age fell in love with his 18-year old student Therese Malfatti. Beethoven did believe that the love was reciprocal, and he was hoping to formally propose marriage at an extensive cocktail party hosted by the Malfatti family. Looking for courage, Beethoven got really drunk and forgot all about proposing. He did apparently play the Bagatelle, but since his handwriting was simply atrocious, it looked like “Für Elise,” and not “Für Therese.” So we still don’t know if “Therese” and “Elise” is the same woman? In the event, Therese married an Austrian nobleman, and the Beethoven dedication might well read “Für Gigons,” Therese Malfatti’s dog.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, WoO 36

Anonymous: Beethoven (1783)

Ludwig van Beethoven was already known around his hometown of Bonn as a brilliant pianist, famed for his stunning improvisations. He made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of seven, and by the age of ten he was already assistant to the court organist in Bonn, Christian Gottlob Neefe. A local critic writes, “This boy of eleven years is a most promising talent. He plays the piano very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well and is now trained in composition. These composition lessons resulted in three piano quartets, written when Beethoven had not yet reached his 15th birthday. They are written in the style of Mozart but the brilliant piano writing already gives a sense of the mature Beethoven. First published after Beethoven’s death, this lively juvenile work is lyrical and charming, but dominated by a sparkling piano part. It is a most rewarding composition in the piano repertoire of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13 “Pathétique”

Prince Carl Lichnowsky

Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in 1792, and he was intent on establishing himself as a pianist and composer in the city. Beethoven was well connected, and members of the Viennese aristocracy openly welcomed him. He astonished his royal friends with his displays of piano virtuosity by playing in salons and giving private performances in their palaces and mansions. The most famous and most popular composition from Beethoven’s early days in Vienna, and one of the greatest works in the piano repertoire is the Piano Sonata No. 8 in C minor, Op. 13. Composed in 1798 and dedicated to Prince Carl von Lichnowsky, it was published under the title “Grande sonate pathétique” in 1799. Importantly, Beethoven himself provided this title from which the general public derived the popular nickname “Pathétique.” Musically, this three-movement sonata “projects an extraordinary coherence of mood, and it foreshadows the cyclical inter-movement connections associated with his mature compositions.” The first movement presents the famous “Grave” introduction, and the “Adagio cantabile” frequently becomes the musical backdrop to cinematographic dramas and soap operas. But it really isn’t sentimental at all, but a beautiful song without words. And the incredible “Rondo Allegro” switches between pianistic virtuosity and grand theatrical gestures.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Quintet for Piano and Winds in E-flat major, Op. 16

Beethoven’s Broadwood Piano, 1817

Although we have some contemporary reports, we really don’t know exactly what Ludwig van Beethoven must have sounded like as a pianist. We do know however, that he wrote many of his sonatas for himself to perform. I think that basically means that the piano parts of his early chamber music were also written to highlight the strengths of his playing. He composed the Quintet for Piano and Woodwinds Op. 16 in 1796, and in the first movement Beethoven is really trying to be serious. While it starts out in the winds, the piano quickly steps into the limelight with a solo flourish. And it doesn’t take very long for the piano to present another cadenza-like flourish. There is much emphasis on the singing quality of the piano in the “Andante cantabile,” with the delicate theme introduced by the piano. And the concluding “Rondo” is like a game of musical chairs, with a big solo cadenza in the first half of the movement. Beethoven played the piano part himself when the work was first heard, and it is reported “he indulged in some extra improvisational activity, fooling the wind players, who at first amused and then disgruntled, were waiting to come back in.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Diabelli Variations, Op. 120

Johannes Gelert: Beethoven (1897) (Lincoln Park, Chicago)

For me personally, the 33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli Op. 120 are the pinnacle of Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano repertoire. One of the greatest sets of variations for solo piano, the pianist Alfred Brendel has described it as ‘the greatest of all piano works.” A scholar adds, “The variety of treatment is almost without parallel, so that the work represents a book of advanced studies in Beethoven’s manner of expression and his use of the keyboard, as well as a monumental work in its own right.” Beethoven takes the smallest elements of the Diabelli waltz and builds upon them pieces of great imagination, power and subtlety. Brendel writes, “The theme has ceased to reign over its unruly offspring. Rather, the variations decide what the theme may have to offer them. Instead of being confirmed, adorned and glorified, it is improved, parodied, ridiculed, disclaimed, transfigured, mourned, stamped out and finally uplifted.” The piano repertoire of Ludwig van Beethoven is vast and incredibly varied. This comes as no big surprise, as the piano, after all, was also Beethoven’s favorite instrument.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Great. That’s what I am doing , return to piano almost daily .