The pianist and pedagogue Heinrich Gustav Neuhaus was one of the most celebrated artists of his generation. His playing was described as “tempestuous,” and at the height of his powers, his technique was considered faultless.

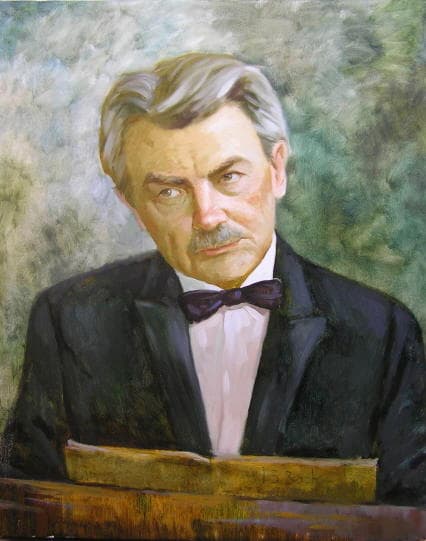

Neuhaus at the piano

As a teacher he shaped several generations of exceptional pianists, with Sviatoslav Richter calling Neuhaus “ an artist of unique genius.”

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 9

Heritage and First Lessons

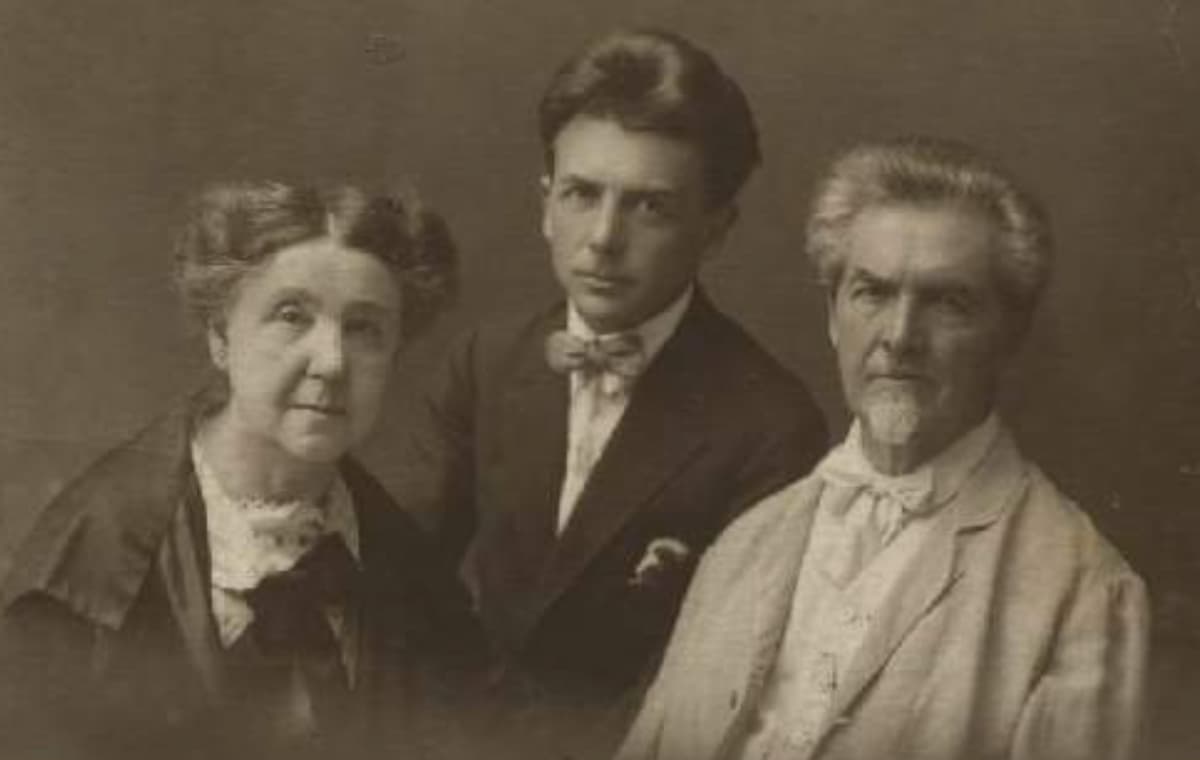

Heinrich Neuhaus was born on 31 March 1888 in Yelisavetgrad (Elizavetgrad) currently named Kropyvnytskyi, a city in central Ukraine situated on the Inhul River. He came from a family of musicians, and both his father and mother were piano teachers. His father Gustav Neuhaus was born in the Rhineland, and he had studied under Ferdinand Hiller. His mother, Olga Blumenfeld, was the sister of Felix Blumenfeld, a distinguished pianist, conductor and teacher who counted Vladimir Horowitz among his students.

Portrait of Heinrich Neuhaus

Surprisingly, Neuhaus was largely self-taught, playing the piano and improvising passionately from early childhood. Scholars have suggested that a major influence on his early artistic development came from Karol Szymanowski, his neighbour and cousin. He did receive sporadic lessons from Felix Blumenfeld, and from Aleksander Michalowski, and he made his first public appearance at the age of 11, playing some Chopin Waltzes and an Impromptu.

Heinrich Neuhaus plays Chopin: Barcarolle in F-sharp Major, Op. 60

Moral Values

As Neuhaus later explained, “I have since my youth had a feeling which persists to this day. Every time I come in contact with a very great man, whether a writer, poet, musician or painter, Tolstoy or Pushkin, Beethoven or Michelangelo, I am convinced that for me the most important thing is that this man is great, and through his art I see a man of tremendous stature and that to some extent it is immaterial whether he expresses himself in prose or poetry, in marble or sound.”

Heinrich Neuhaus and his parents

Neuhaus grew up not only in a highly musical household, but also in an environment that was well-versed in the writings of German philosophy and literature. It decisively shaped his aesthetic view, as he explained, “since my childhood I was infected not only by the musical bacillus, but to an even greater degree by morals: aesthetic questions, questions of dignity, human values, of the beauty of man’s soul, of spiritual greatness concerned me not less, if not more, than the most beautiful sonatas of Beethoven.”

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30, Op. 109

Godowsky and Barth

Gustav Neuhaus was looking to increase his son’s exposure to Germanic aesthetics and thought, and he sent his son for pianistic training to Berlin and Vienna, and instruction with Leopold Godowsky and Karl Heinrich Barth. Surprisingly, young Neuhaus was not able to relate to the atmosphere he encountered in Central Europe. As he writes, “I can’t wait to return home. In Berlin there is something stupid and painfully weary. Nowhere like here does one feel that there is no truth, everything is permitted.”

Neuhaus as a young man

Neuhaus did study with Godowsky in Berlin, however, he confessed that “while studying with Godowsky I thought more and more about Busoni, who was substantially higher and more interesting.” He also took lessons from Karl Bath in Vienna and concordantly studied composition from Paul Juon. Neuhaus readily acknowledged that Busoni, Godowsky, his uncle Blumenfeld and his cousin Szymanowski balanced performance and composition in shaping their artistic identities. Neuhaus, on the other hand, rejected the suggestion to prioritize composition over performance.

Heinrich Neuhaus Plays Rachmaninoff

Return to Russia

After Neuhaus had returned to Russia at the outbreak of the First World War, he began teaching at the Moscow Conservatoire and was instrumental in creating the famous Moscow Central Music School for specifically gifted children in 1932. Between 1934 an 1937, Neuhaus was Director of the Moscow Conservatoire, a post he relinquished in order to be able to devote himself entirely to teaching.

Neuhaus and Richter

Throughout his pedagogical career, Neuhaus strongly believed that a musician should be able to communicate a rich cultural and emotional content through his interpretations. As he explained, “the goal of emotive art is first and foremost the creation, on stage, of a living life of the human soul and the reflection of that life in the artistic stage-form.

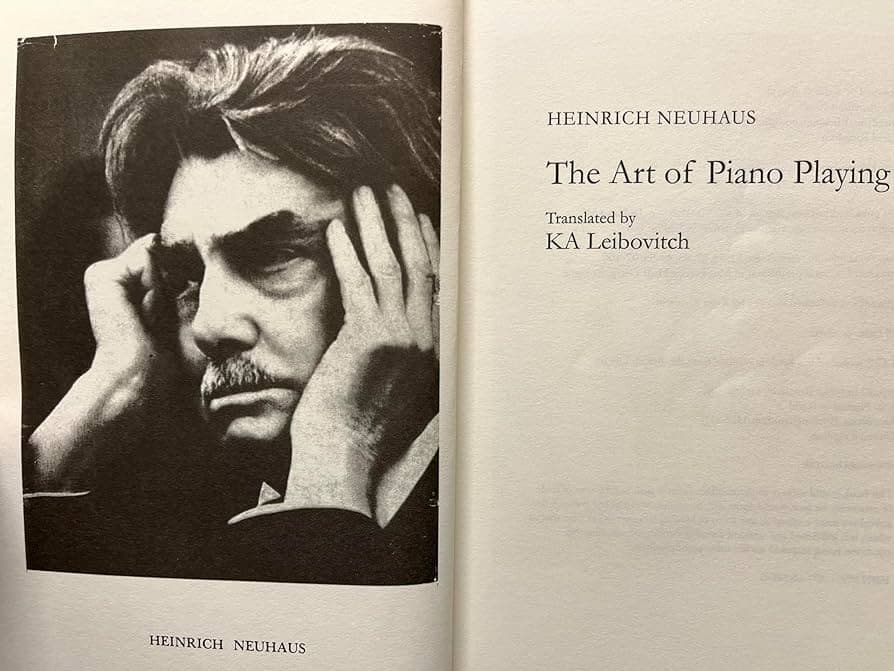

Neuhaus: The Art of Piano Playing

Neuhaus codified his main principles of performance and his teaching in his publication About the Art of Piano Playing in 1958. A biographer wrote, “seldom have artistic gifts been so closely matched by the qualities of selfless devotion, deep humanity, true culture and a great capacity for bestowing and winning friendship.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter