Vincenzo Bellini

Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) was the quintessential composer of the Italian bel canto era during the early 19th century. His last opera I Puritani (The Puritans) was first staged in Paris in January 1835, and it is based on a deeply obscure French play. Although handicapped by an inept libretto, it is one of Bellini’s most ambitious and beautiful works. Bellini wrote to a friend after the premiere, “The French have all gone mad; there were such noise and such shouts that they themselves were astonished at being so carried away… In a word, it was unheard of thing, and since Saturday, Paris has spoken of it in amazement.” One writer, who had plenty to say about Bellini, and Parisian musicians and society in particular, was Heinrich Heine. Bellini met Heine at a dinner gathering during the summer of 1835. Apparently, Heine remarked, “You are a genius, Bellini, but you will pay for your great gift with premature death. All the great geniuses died very young, like Raphael and like Mozart.”

Vincenzo Bellini: I Puritani, “Vien, diletto, e in ciel la luna”

Giovanni Battista Rubini as Arturo in I Puritani

Bellini was a highly superstitious person, and he was horrified. All attempts at reconciliation failed, and the phobic aspect of Bellini’s personality would eventually make it into Heine’s unfinished novel Florentine Nights, published in 1837. Unflatteringly, Heine considered the composer “a sigh in dancing pumps.” In the event, Bellini fell ill in early autumn of 1835. As he wrote to a friend on 16 August, “for three days I’ve been slightly disturbed by diarrhea, but I am better now, and think it is over.” Slight improvements were reported on 20 September, and the doctor suggested that he “hoped to declare him out of danger tomorrow.” However, Bellini’s health did not improve and he passed a very restless night and day shaken by “terrifying convulsions.” Bellini died in the afternoon of 23 September 1835 at the age of 34. The distinguished Court-appointed Doctor Dalmas performed the autopsy and reported “Bellini succumbed to an acute inflammation of the colon, compounded by an abscess in the liver.”

Vincenzo Bellini: Norma, “Casta diva”

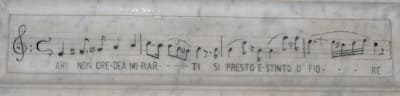

Bellini’s inscription on the tomb

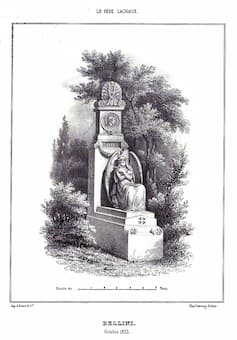

Gioachino Rossini immediately took charge of all arrangements, including plans for Bellini’s funeral and entombment, as well as caring for his estate. He created a committee of Parisian musicians in order to find support for a subscription to build a monument to the dead composer, as well as supporting a funeral mass to be celebrated on 2 October in the chapel of the Hôtel des Invalides. Of the many tributes that poured forth following Bellini’s death, Felice Romani’s touching praise was published in Turin on 1 October 1835. In it, he wrote, “perhaps no other composers know as well as Bellini the necessity for a close union of music with poetry, dramatic truth, the language of emotions, the proof of expression. I sweated for fifteen years to find a Bellini! A single day took him from me!” The funeral turned out to be a grand occasion and featured the immortal Labalache alongside the young Russian tenor Nicolai Ivanoff, and the great Giovanni Rubini. Cherubini, Carafa, and Rossini featured as pallbearers, and Francois-Antoine Haberneck was in charge of the music. A contemporary reports, “even though it rained continuously, the funeral was attended by the most noted musicians and artists in Paris.” Bellini was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery, and after nearly 40 years of squabbles between French and Sicilian officials, Bellini’s remains were moved to the Cathedral of Catania in 1876.

Vincenzo Bellini: La Sonnambula, “Ah! Non credea mirarti”

Monument of Bellini

A tomb was designed by the sculptor Giovanni Battista Tassara and carries a musical inscription from Amina’s last aria on Bellini’s tomb, La sonnambula: “Ah! Non credea mirarti / Sì presto estinto, o fiore” (I did not believe you would fade so soon, oh flower).

The legacy of Bellini was immediately felt in the early works of Richard Wagner and his contemporaries, and Bellini’s unique Italianate capacity for expressiveness also reverberated in the instrumental music of Chopin and Liszt. Bellini created extraordinary fusions of sublime melody, vocal challenge, and dramatic power. Gustav Mahler confessed that he was unable to listen to Norma without tears, and Richard Wagner was so carried away during the final scene that he was sure the opera had been written by god! Franz Liszt was initially not a great fan of Bellini, describing him as “a fair-haired, weak, womanish, poor-spirited man with the seeds of consumption in him; with elegant laissez-faire and with melancholy grace of his whole mental and bodily outfit.” However, Liszt was clearly attracted by Bellini’s enormous popular appeal. Besides providing various transcriptions and paraphrases, Liszt also composed a number of fantasies that weave together different themes from the opera, as in his Reminiscences de Norma.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: Reminiscences de Norma