Judith Bingham: Roman Conversions

In her 2017 organ work, Roman Conversions, British composer Judith Bingham looks at ‘five metamorphoses’ that happened in Rome, beginning in ancient times and concluding in the Baroque.

Her first movement describes the setting: San Clemente: a Mithraic temple lies under two medieval churches. Underneath the Basilica of Saint Clement (Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano), built around 1100, lies a 4th century house of a Roman nobleman, part of which dates back to the first century when it served as an early church. In the basement of that house was a mithraeum from the 2nd century. In that basement was found an altar and an image of Mithras slaying a bull. Temples to Mithras were supposed to be images of the universe in miniature and are found all over Europe and in Western Asia (Syria and Israel).

San Clemente

Mithraeum at San Clemente

In her work, Bingham starts in the dark and mysterious world of the underground mithraeum before emerging into the light of the basilica 35 feet above.

Judith Bingham: Roman Conversions – I. San Clemente: a Mithraic temple lies under two medieval churches (Tom Winpenny, organ)

Bingham next looks at two statues from the Borghese Collection. The first is the conversion of Daphne, fleeing the lustful Apollo, into a laurel tree and the second is the mixed gender figure of Hermaphroditus.

Commissioned by Cardinal Borghese, Bernini executed the statue of the critical moment when Daphne’s pleas to her father, Peneus, a river god, are answered and she is forever removed from Apollo’s grasp. He was struck by Cupid’s arrow that excites love and she was struck by Cupid’s opposite arrow that denies love. As Ovid’s Metamorphses, Book I, puts it:

Destroy the beauty that has injured me, or change the body that destroys my life. Before her prayer was ended, torpor seized on all her body, and a thin bark closed around her gentle bosom, and her hair became as moving leaves; her arms were changed to waving branches, and her active feet as clinging roots were fastened to the ground—her face was hidden with encircling leaves.

And so we see the roots emerging from her toes and her arms turning into branches.

Bernini: Apollo and Daphne, 1622-1625 (Galleria Borghese, Rome)

In her music, Bingham seems to capture both the intertwining of the branches and the stillness that lies at the heart of every tree. The organ figures move and twist upward.

Judith Bingham: Roman Conversions – II. Bernini’s Daphne and Apollo (Tom Winpenny, organ)

Viewed from the back, the anonymous statue of Hermaphroditus appears to be very feminine in its curves and wavy hair. Viewed from the other side, however, the double sex of the figure becomes apparent. The child of the gods Hermes and Aphrodite, the boy was so remarkably handsome that the naiad Salmacis attempted to rape him and prayed to be united with him forever. A god answered her prayer and so the two were merged forever. The statue comes from ancient times, but the mattress the figure rests on was sculpted by Bernini in 1620. The sculpture was purchased in 1807 and moved to France where it is now in the Louvre Museum.

Anonymous / Bernini: Sleeping Hermaphroditus (Louvre Museum)

In her music for Hermaphroditus, Bingham uses triplets to create a mesmerizing rhythm that captures the figure’s character.

Judith Bingham – Roman Conversions: III. The Sleeping Hermaphrodite (Tom Winpenny, organ)

The fourth movement, William Shelley, son of an English poet is transformed into seed and flowers, is based on a poem written by Percy Shelley at the death of his 3 ½-year-old son in Rome in 1819. In the poem, Shelley wants to think that above his grave, his ‘spirit feeds…sweet flowers’.

Amelia Curran: William Shelley, 1819 (Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley

and His Circle, The New York Public Library)

To William Shelley

1.

My lost William, thou in whom

Some bright spirit lived, and did

That decaying robe consume

Which its lustre faintly hid,?

Here its ashes find a tomb,

But beneath this pyramid

Thou art not? if a thing divine

Like thee can die, thy funeral shrine

Is thy mother’s grief and mine.

2.

Where art thou, my gentle child?

Let me think thy spirit feeds,

With its life intense and mild,

The love of living leaves and weeds

Among these tombs and ruins wild;?

Let me think that through low seeds

Of sweet flowers and sunny grass

Into their hues and scents may pass

A portion?

Percy Shelley

In the scherzo movement, Bingham makes the organ represent the riot of flora above the grave of the dead child.

Judith Bingham: Roman Conversions – IV. William Shelley, son of an English poet is transformed into seed and flowers (Tom Winpenny, organ)

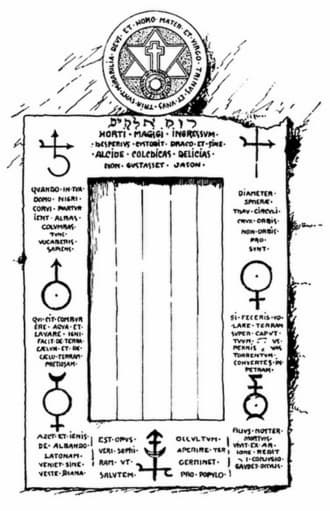

The final movement is about a mysterious doorway in Rome known as the Magic Portal or the Alchemical Door. It was built between 1678 and 1680 by Massimiliano Palombara, at the villa Palombara in Rome. The Magic Portal is the only door remaining of the original 5 doors that had occult inscriptions. The wall has become part of the Piazza Vittorio in Rome.

The Magic Portal, 1680 (Rome, Piazza Vittorio)

According to a story collected in the 19th century, a pilgrim searched the garden for a mysterious herb that would help in the alchemical search for the recipe for creating gold. In the morning, he disappeared forever through a door but left behind evidence of his success in transforming gold. He also left behind a paper of symbols that described his successful experiment and this was engraved on the door in the hope that later alchemists would be able to use it.

The Magic Portal’s engravings

Bingham uses this doorway as the inspiration for the climax of her work. Building in a slow crescendo, she evokes the enigmatic and impassible doorway – should you solve the alchemical equation, you can pass through the door, but where will you end up?

Judith Bingham: Roman Conversions – V. Porta Alchemica (Tom Winpenny, organ)

Taking not one artist as her point of departure but rather a concept, Bingham has created a work that alternately gives us images and gives us concepts of change. We are ourselves converted through the work – taken to a new world through the final mysterious door.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter