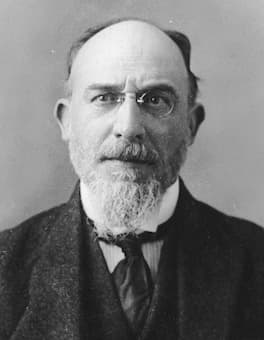

Erik Satie, 1884

Decades of heavy alcohol consumption finally caught up with Erik Satie in February 1925. He started to experience a rapid decline in health due to cirrhosis of the liver and pleurisy in January 1925, and he was initially cared for by Milhaud, Braque, and Derain. Jean Wiéner arranged a room for him at the Grand Hôtel, Place de l’Opéra, but Satie was not satisfied and moved to the Hôtel Istria at Montparnasse. When his health declined further, the Compte Etienne de Beaumont arranged a private room for him in the Hôpital Saint-Joseph, rue Pierre-Larousse on 15 February. Darius Milhaud gave a description of Satie in the hospital. “He had never been ill before, and everything gave rise to dramas, from taking medicine to having his temperature read. Satie asked Madeleine Milhaud to pack his suitcase. As she knew he was likely to fly into inexplicable rages if things were not placed exactly in the way that he wanted them, she asked Braque to stand between them so that Satie might not be able to watch how she packed his case. Despite his intolerable sufferings, he still retained his own characteristic brand of wit. When Jacques Maritain brought a priest to see him, he described him to us next day as looking like a Modigliani, black on a blue background.”

Erik Satie: Ludions (Elaine Bonazzi, mezzo-soprano; Frank Glazer, piano)

Erik Satie house in Arcueil

When Monsieur Lerolle came to see him about publishing Relâche, Satie insisted on being paid at once. “You never need money so much as when you’re in a hospital,” he supposedly remarked. Milhaud writes, “Hardly had Lerolle paid over the money, when Satie hid the banknotes between the sheets of old newspapers piled up on his suitcase.” Milhaud reports that once Poulenc gained knowledge of Satie’s illness, he begged to see him. Satie was touched by this, but refused saying “No, no, I would rather not see him; they said goodbye to me, and now that I am ill, I prefer to take them at their word. One must stick to one’s guns to the last.” Satie had broken ties with Poulenc during the Monte Carlo season in 1924, and Satie remained uncompromising as he also refused to see other past friends with whom he had quarreled. The young composer Robert Caby, whom he had met in 1923, cared for him during his final days. Satie’s death was announced at 8pm on 1 July 1925. He only had reached the age of 59, and the funeral took place on 6 July at the cemetery at Arcueil.

Erik Satie: Mercure (Orchestre de Paris; Pierre Dervaux, cond.)

Satie late in life

Satie never allowed anything to be thrown out, and loved to accumulate all kinds of odds and ends. In addition, Satie had never allowed visitors to enter his room in the southern suburbs, in the commune of Arcueil-Cachan, eight kilometers from the center of Paris. When his brother Conrad together with Milhaud, Désormière, and Robert Caby finally entered his room, they described it as “squalid.” In fact, they “had to evict two cartloads of accumulated rubbish before they could begin to sort out his papers and manuscripts.” Several scores to important works believed lost were found among the accumulated rubbish, and while the letter he kept were later destroyed in a fire at Conrad’s home, his notebooks and scores were preserved by Milhaud. One of his last collaborators, Picabia wrote, “Satie’s case is extraordinary. He’s a mischievous and cunning old artist. At least, that’s how he thinks of himself. Myself, I think the opposite! He’s a very susceptible man, arrogant, a real sad child, but one who is sometimes made optimistic by alcohol.”

Erik Satie: Musique d’ameublement (Bernard Jeannoutot, trumpet; Ensemble Ars Nova; Marius Constant, cond.)

Tomb of Satie

During his lifetime and in the years since, Satie has often been described as “child-like.” Madeleine Milhaud explained, “Satie led a sad life, rather lonely. He was attracted by young children, by youth and purity as he shared their joys and hopes. They made up for a deficiency in his own character and they took him as a sort of mascot and thought he brought them luck.” In a posthumous account of Satie, a critic wrote in Le Figaro that Satie “took possession of glory smiling his familiar sardonic smile, in the manner of a child that mounts a hobby-horse, without believing in it, but dreaming however that it is an authentic mount.” In a review of Parade Satie is infantilized, “in order to criticize the quality of his music.” The critic alludes to “Freud’s work on developmental child psychology, specifically his theory of the anal phase of infantile sexuality.” However, not everybody considered Satie’s associations with childishness as necessarily negative. For a good many critics, “Satie was a young composer and a testament to the freshness of his musical ideas.” Shortly after Satie’s death, the artist Fernand Léger suggested that Satie’s youthfulness translates into the process of constant renewal and innovation in his art. He writes, “a music that is no longer music, that is completely new music; an imponderable thing, distinct, undefined, very defined, we don’t know any more. It did not come from the orchestra, it is below the orchestra, it is on the plateau, in the hall, under the hall, in the legs of the dancers, in the electric lamps, behind the projectors, it is that music of the youngest French composer.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Erik Satie: Relâche