Thea Musgrave: The Seasons Inspired by Paintings From the 15th to 20th Century

When we think of a musical work called The Seasons, we first think of Vivaldi’s set of violin concertos or Glazunov’s ballet or Tchaikovsky’s cycle for piano, or perhaps even Piazzolla’s Four Seasons of Buenos Aires. Scottish composer Thea Musgrave (b. 1928), however, wrote her orchestral work The Seasons based less on atmospheric conditions than on paintings dating from the 15th to the 20th century.

Commissioned by The Academy of St Martin in the Fields in 1988, Musgrave based her work, The Seasons, starting with Piero di Cosimo’s violent Caccia Primitiva where animals fall to man and to each other in a grisly hunting scene. In the background, a fire rages, filling in the spaces between the trees with a red glow. Smoke and birds fill the air. The inspiration for Piero di Cosimo was the rediscovery in 1417 and the publication in Florence in 1471 of Lucretius’ fifth book of De Rerum Natura. ‘Lucretius believed that the workings of the world can be accounted for by natural rather than divine causes, and he put forward a vision of the history of primitive humanity and the advent of civilization…’ that Piero di Cosimo pictured. ‘Nature red in tooth and claw’, as Tennyson put it, comes to life and death here.

Piero di Cosimo: Caccia Primitiva, ca 1494-1500 (New York: Metropolitan Museum)

Musgrave is using the images not as a cycle of the seasons but as a metaphor for the cycles in the life of man. In Autumn, we have the approaching storm and, on the ground, a grim battle for life. The fire drives all before it and they confront each other in a vicious bloody conflict. In the music, hunting horns have a prominent part while behind it all is restless.

Thea Musgrave: The Seasons – I. Autumn (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; Thea Musgrave, cond.)

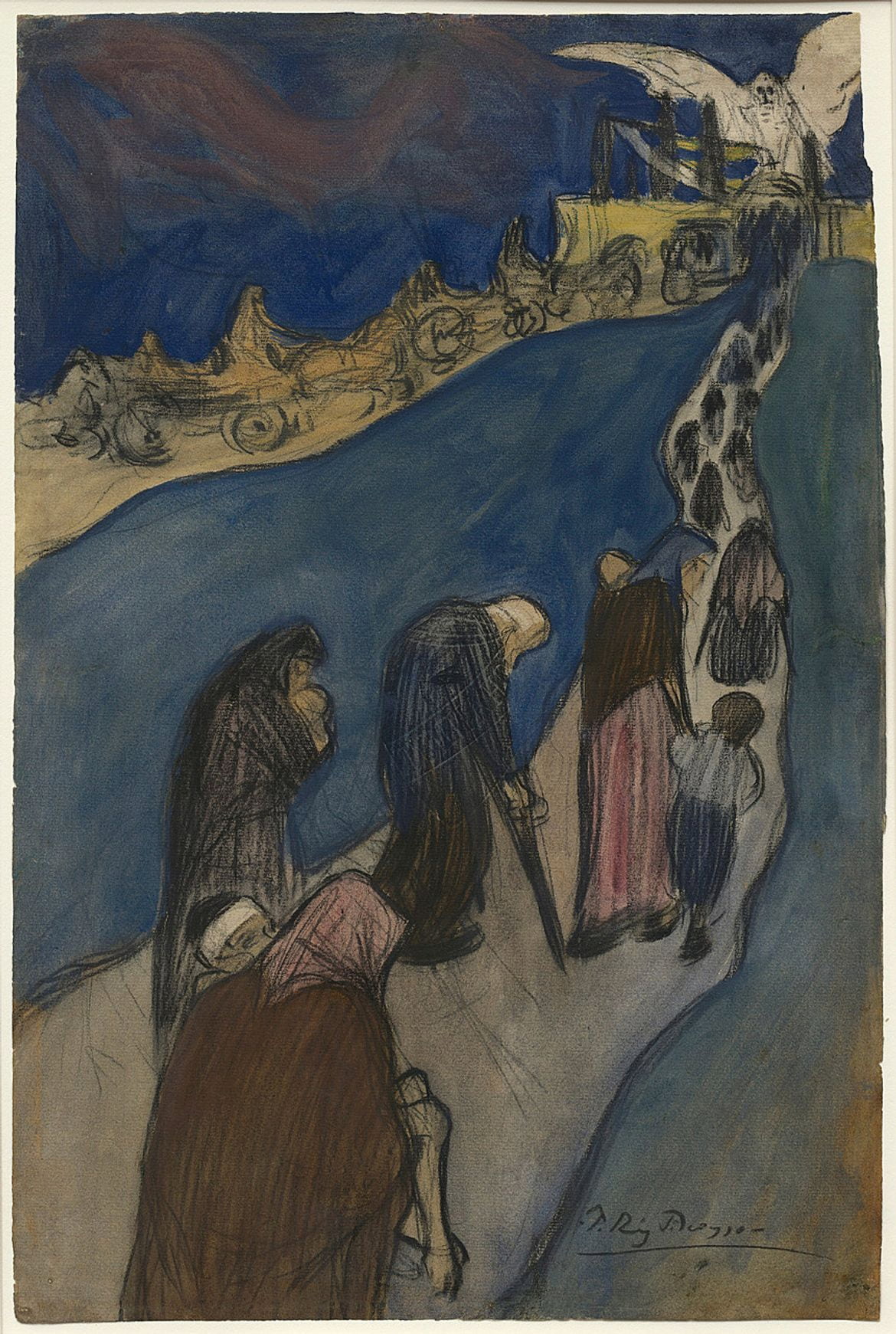

In the end, the Requiem chant Dies Irae makes an appearance in the bells (06:55), inspired by an early work by Picasso, Au bout de la route (The End of the Road). Created in 1899-1900, he completed it before his first exhibition in Barcelona in 1900. The old and the young, the sick and the burdened trudge along a path, only to be met at the end by an angel, perhaps the angel of death.

Pablo Picasso: Au bout de la route (The End of the Road), 1899-1900 (Guggenheim Museum)

Winter, with its frozen ground and chill, all around was inspired by one of the most famous pictures in American art, Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware. Washington stands in the boat, looking toward the far shore where his enemies are encamped. In his boat, his cold boatmen push ice flows out of the way or grab desperately at the open water for their oars. No one is in uniform, and few are even wearing gloves. At the back of the boat, a man steers with his oar acting as a rudder, his clothes reflecting that he might have been one of Washington’s followers from the American Indian population.

Leutze first painted this image in 1849, but it was damaged by a fire in his studio in 1850. He restored it and it was acquired by the Bremen Art Museum, only to be destroyed in a 1942 bombing raid. This version was painted afresh in 1850 and it was exhibited in New York in 1851 and promptly purchased for $10,000 (about $360,000 today). In 1853, it was made into an etching and remains one of the most distinctive images of the first President.

Emanuel Leutze: Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851 (New York: Metropolitan Museum)

In Winter, Musgrave evokes the chill silence of the season, but then a single voice, an oboe, sounds to bring us a small flicker of warmth and hope. We faintly hear a brief quote from The Star-Spangled Banner, written during a different war in America.

Thea Musgrave: The Seasons – II. Winter (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; Thea Musgrave, cond.)

In Spring, the rains come and with them a rebirth in bird song. The farmers emerge from their houses to begin the spring planting. Van Gogh seems to use colour symbolically: the sky is green-yellow and the dark earth is given in purple. The bright yellow sun forms a halo around our (saintly) harbinger of spring. Painted in Arles in 1888, the painting shows us the promise of spring – sow today for the plenty of tomorrows.

Van Gogh: The Sower, 1888 (Van Gogh Museum)

Musgrave opens with bird song, a twittering of expression as the birds who have been invisible all winter return and fill the air with their music. She also gives us the drama as living things fight their way into the world and at the end, we hear the distinctive notes of the cuckoo.

In the middle, however, as the music builds to a climax, Musgrave inserts two massive chords. These are quotations from her opera Harriet, The Woman Called Moses, where they symbolize freedom.

Thea Musgrave: The Seasons – III. Spring (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; Thea Musgrave, cond.)

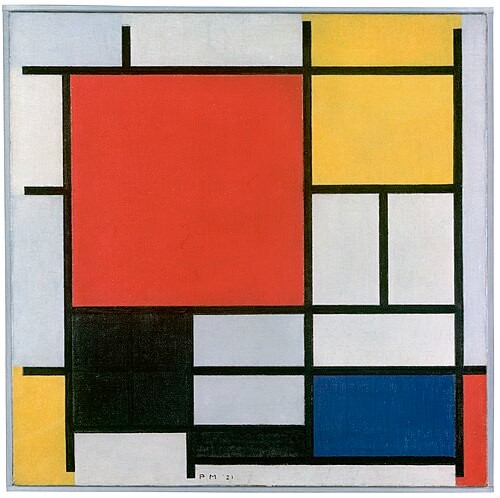

Summer is a celebration and Musgrave looked to art reflecting both French and American national celebrations for her inspiration.

Jasper John’s Flag was created in 1954-55 using a building technique that started with a background collage of newspaper scraps. On top of that, he used paint and encaustic, a mixture of pure colour and melted wax that preserves both the paint’s drips and the smears and brushstrokes of the artist. The 48 stars were correct for 1955 as the 49th and 50th states, and their stars weren’t added until 1960.

Jasper Johns: Flag, 1954-55 (New York: MoMA)

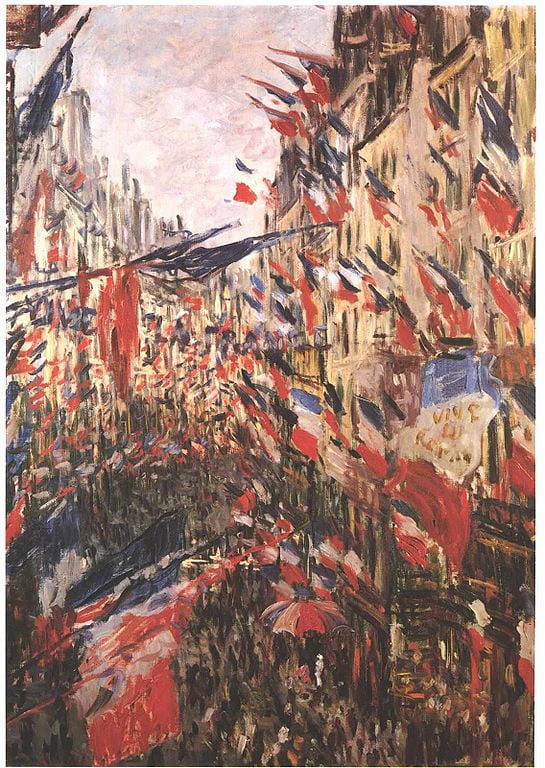

From France, we have two different artists marking national days in France. First, we have Monet’s colour-saturated Rue St-Denis, Festivities of June 30, 1878. The Parisians have flooded the streets to commemorate the ‘first official national celebration to take place following the defeat of Napoleon III in 1870.’ Concurrent was the opening of the 1878 Universal Exhibition. The tricolour dominated the streets and Monet chose to show this from a high perspective. The dark triangle of the crowds on the street is matched by the light triangle of the visible sky above. But it’s the flags, fluttering, flapping, and twisting on display that dominates the scene. Declaring the vision to be ‘musical’, the painting was purchased 2 months later by the composer Emmanuel Chabrier for his own collection.

Claude Monet: Rue St-Denis, Festivities of June 30, 1878, 1878 (Musée de Rouen)

Ten years later, Vincent van Gogh gives us Bastille Day in Paris from street level. Like Monet’s image, this is also saturated in flags. The tricolour is everywhere except in the pedestrian’s clothes. Van Gogh had just arrived in Paris and the national celebrations for Bastille Day brought out the colour he’d been repressing in his Dutch painting. This is impressionism, or perhaps even fauvism, in a way that only van Gogh could do.

Van Gogh: The 14th July in Paris, 1886 (Foundation Hahnloser / Jaeggli)

Musgrave, like each of the artists who inspired her, layers her musical elements in Summer. The national anthems of France and the US are placed over each other and the sense of celebration in the two French paintings comes through the music. Even the cuckoo makes a reappearance.

Thea Musgrave: The Seasons – IV. Summer (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra; Thea Musgrave, cond.)

By ending with Summer, Musgrave ends on the brightest note of the year. But, having taken us through the struggles for life in Autumn, the frozen wastes of Winter, and the work of Spring, it’s Summer where we can celebrate. In her music, Musgrave has used a single chord (C-E-flat-G-B) in every movement but in a different octave. This is also part of the ‘Freedom Chords’ at the climax of the Spring movement.

Musgrave has given us a far more personal view of the seasons than those offered by other composers and also, a one that spans centuries and continents. She has also given us a work that sparks reflection and thought – How grim does Autumn have to be? What brings hope in Winter? What does Freedom mean in Spring? Is hysterical nationalism always good? This isn’t Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, this is four seasons of reflection and thought.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter