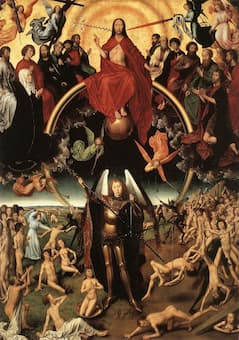

Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff:

The Dance of Death, 1493 (Nuremberg Chronicle)

Composers make up melodies all the time and create new and innovative pieces to show off those talents. Occasionally, though, they go back to older melodies, even melodies that they may not have written, and use them to make a particular emphasis.

One melody that has been used for centuries is created to set the 13th century Italian poem ‘ Dies irae.’

As a poetic work, it is characterized by strong accents and rhymes. It continues on in this same style for over 50 lines.

Dies iræ, dies illa, | The day of wrath, that day, |

Solvet sæclum in favilla: | will dissolve the world in ashes: |

Teste David cum Sibylla. | (this is) the testimony of David and the Sibyl. |

If you read Latin, you’ll realize that it’s a series of strong and weak accents: Dies iræ, dies illa. This pattern of a strong and a weak syllable is called the Trochee and the rhythm gives us Trochaic Meter.

The trochee is so strong as a pattern that when it appears in the middle of classical music, it commands our attention immediately. And, because we know the history of the poem and its use in music, we get extra-musical references as well.

Anonymous: Dies irae [Messe des Morts: Sequence] (Choeur des Moines de l’Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes; Joseph Gajard, cond.)

The Dies Irae was used as the sequence, a chant or hymn sung during the mass, for the Requiem Mass. When you hear it, you should think of the extra-musical ideas of death, punishment, the Last Judgement, and other ends of the world calamities.

Here are a few pre-classical, classical and modern uses of this chant.

In this opening part of a Dies irae setting by Lully, we can hear that when the choir enters, all the lovely music that preceded it is immediately marginalized as the strong Dies Irae melody takes over.

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Dies irae (Sophie Junker, Judith van Wanroij, sopranos; Thibaut Lenaerts, Mathias Vidal, Cyril Auvity, tenors; Alain Buet, bass; Namur Chamber Choir; Millenium Orchestra; Leonardo García Alarcón, cond.)

In a shocking style, as was true of so much of his music, Berlioz’ introduction of the Die Irae melody into his Symphonie fantastique, his drug-fueled inquiry into ‘episodes in the life of an artist,’ is done in a completely modernistic manner. Coming in at the first early in the movement (03:27) its performance by 4 bassoons and 4 ophicleides (trombones are often substituted for this now-rare instrument), starts out straight and solemn before being interrupted by the higher brass playing the melody in a faster style, with the woodwinds skipping around the high brass. The low instrument repeat, and on the third iteration, the high brass has almost removed every accent in the melody.

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – V. Songe d’une Nuit du Sabbat (London Classical Players; Roger Norrington, cond.)

Centre panel from Memling’s triptych Last Judgment

(c. 1467–1471) (Muzeum Narodowe, Gdansk, Poland)

When the melody returns again at the end, it forms a rock-solid basis against the strangeness in the upper voices. The whirling dance that starts at 07:55 eventually meets the uncompromising Dies Irae melody at 08:40 and it’s now more like a march with twirling batons than a death procession. There’s one last appearance of the melody at 9:59 before it’s buried by all the other action.

Franz Liszt had a fascination with death and this can be seen in some of his titles, including Totentanz, Funérailles, La lugubre gondola, and Pensée des morts. He discovered the Die Irae melody when he made a piano transcription in 1833. Five years later, he started work on Totentanz: Paraphrase on Dies Irae for piano and orchestra. This variation set takes great freedom with the melody, first emphasizing its plodding trochees, and then contrasting the melody in as many ways as possible: timbre, rhythm, texture, and tempo, just for a starting list.

Franz Liszt: Totentanz, S126/R457 – Andante – Allegro – Allegro moderato – (Alfred Brendel, piano; Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Michael Gielen, cond.)

The music critic Richard Pohl, an early advocate of and biographer of Liszt, noted that ‘Every variation discloses some new character—the earnest man, the flighty youth, the scornful doubter, the prayerful monk, the daring soldier, the tender maiden, the playful child.’

By the final section, we’ve been so exposed to this melody of the dance of death and we can feel we’d know it anywhere. Liszt finishes in a glorious manner for both pianist and orchestra.

Franz Liszt: Totentanz, S126/R457 – Allegro animato (Alfred Brendel, piano; Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Michael Gielen, cond.)

Sorabji, 1917 (photo by Histead)

Other composers took up the Dies Irae melody. The English composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji created a set of 27 variations on the melody in his Sequentia cyclica… that takes nearly 8 ½ hours to perform, with some of the individual variations approaching an hour in length. Sorabji was fascinated with the melody and used it in 10 of his works. In the 1920s, he wrote the smaller Variazioni e fuga triplice sopra “Dies irae” per pianoforte and in the late 1940s, wrote the larger Sequentia cyclica super “Dies irae” ex Missa pro defunctis, both based on the melody.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Sequentia cyclica super Dies irae – Theme (Jonathan Powell, piano)

Sorabji closes this enormous work with a series of five fugues on the melody, starting with a two-voice fugue and ending with a massive six-voice fugue. By the end of this super variation set, the theme is now reduced to just a few notes: the first four pitches and some general downward motions. But, having heard that melody over the past 8 hours continues to make it unforgettable.

To us, it may seem morbid to focus on what we might consider to be the melody and rhythm of death, but for many people in the 19th century, it was a common occurrence; even now, coming out of the world’s COVID lockdown, we could be thinking the same kind of morbid thoughts.

Next, we’ll explore the Dies Irae in the hands of composers who want to write new melodies for it.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter