Handel: Messiah – Part III: Amen

In his seminal study on counterpoint and fugue, Alfred Mann writes, “There is probably no branch of musical composition in which theory is more widely, one might almost say hopelessly, at variance with practice than fugue.” Basically, Mann is telling us that there is no such thing as fugue-form in the usually accepted sense and meaning of the word form in music, which is a plan or structure broadly fixed. Rather, a fugue is not a thing made to fit into a particular mold; it is a compositional procedure, not a form. For George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) fugue was a pliable process that primarily served a dramatic purpose. While he did compose some wonderful textbook fugues, his choral fugues are free, unpredictable, and gloriously unregulated. Attracted to the polyphonic practices of Italian lands—far freer than those of German composers—Handel used fugal techniques to communicate a special effect or moral. The final ‘Amen” chorus from his Messiah, building through the choir and orchestra, is a master class in raising tension in music. This fugue is a triumphant affirmation, not just of the Messiah story, “but of any prayer, public or private.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah – Part III: Amen (Chorus) (Collegium Vocale 1704; Collegium 1704; Václav Luks, cond.)

Robert Schumann, 1839

Robert Schumann’s (1810-1856) mental health took a turn for the worse in 1844. On the advice of the court physician in Dresden, Schumann started a course of hypnotherapy under Dr. Helbig. That particular therapy turned out to be unsuccessful, but Schumann soon found a more fruitful treatment in his study of counterpoint and fugue. He set to work on his Six Fugues on the name of Bach, sets of Studies for the Pedal Piano and the Four Fugues, Op. 72. His fugal tribute to the great Leipzig master was complete in 1846, and when Schumann offered the completed work to his publisher, he appended the following note, “it is a something I worked on the whole of last year, to make it worthy of the high name that it bears, a work which I think might perhaps survive my other works the longest.” It had indeed been hard work, as Schumann confided in a friend. “For my part there was no lack of hard work and effort; on no other of my compositions have I so long hammered and chiseled.” Since it had taken a year, it is not surprising that the work is an example of contrapuntal mastery. However, it also recreates and redefines the discipline and structural logic of Bach’s music in nineteenth century terms. “The six pieces are very varied in style, and together they form a great fugal symphony, an epic journey through ever-changing landscapes of simplicity and complexity, darkness and light.”

Robert Schumann: 6 Fugues on B-A-C-H, Op. 60 (Roberto Marini, organ)

Carl Joseph Begas: Felix Mendelssohn, 1821

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) was the ultimate musical prodigy. Between the ages of 12 and 14, he composed 13 symphonies for strings, with the occasional surprise entries for percussion. He also produced songs, piano pieces, operas, and chamber music in astonishing profusion while all the time marching toward the maturity that emerged with the famous Octet and the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, all written before he was 17. Of course we know that Mendelssohn was “well educated, privileged since childhood by money and all the access money could purchase.” And it was family wealth that permitted Felix to study with Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832). While Zelter was primarily known during his lifetime as a composer, conductor and teacher, his greatest legacy was in creating comprehensive music education programs and training institutions throughout Germany. He imposed a strict regime of counterpoint and fugue on the young Mendelssohn, and instructed him in voice leading and instrumentation. Mendelssohn soaked up everything effortlessly and his inclination towards strict contrapuntal techniques in his music was surely conditioned by his studies with his beloved teacher. Just listen to the “Finale” of his 7th String Symphony, where the second theme introduced by the viola gives rise to a splendid fugue. Mind you, Mendelssohn was only 13 when he composed this particular gem.

Felix Mendelssohn: Sinfonia No. 7 for Strings, “Allegro Molto” (English String Orchestra; William Boughton, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky in 1930

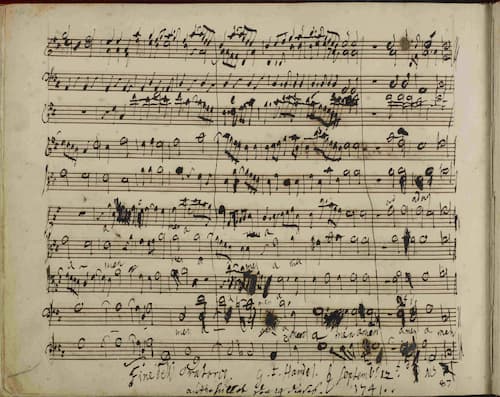

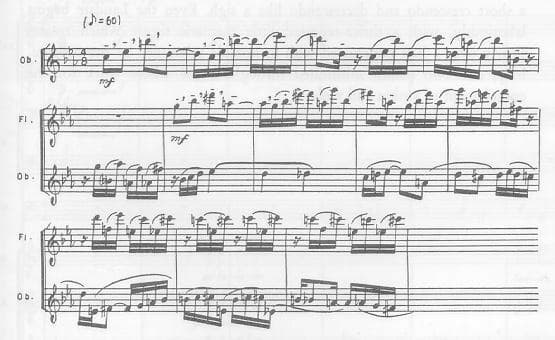

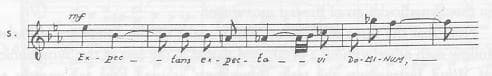

When Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) departed France for Switzerland in 1920, he musically left behind the lavish grandeur of his famous Ballets. Abandoning large orchestral forces, he began to prefer chamber and choral ensembles, and the solo piano. This switch to a smaller, more intimate orchestration coincided with a transformation of his musical conception and language. Stravinsky replaced the exaggerated gestures of late Romanticism and the expressive indulgences of the recent past, with works that revived the balance and clearly perceptible thematic processes of earlier musical styles. Stravinsky became the leader of a new generation of young composers that espoused the tradition of pure music and the beauty of form of classicism under the banner “Return to Bach.” The second movement of his Symphony of Psalms presents a haunting double fugue. The first fugue theme is introduced by the oboe and subsequently combined with the second theme presented by the soprano. The fugal procedure is pure Bach, but the musical language is pure Stravinsky. By casting his fugal themes in different keys Stravinsky succeeded in transitioning his double fugue into a multidimensional structure.

Igor Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms, “Expectans expectavi, Dominum” (Stuttgart Radio Choir; Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Gary Bertini, cond.)

Igor Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms, theme of the 1st fugue

Igor Stravinsky: Symphony of Psalms, theme of the 2nd fugue

Canzi and Heller: Portrait of Liszt, 1860s

When Clara Schumann first heard Liszt’s B minor Sonata, which was after all dedicated to her husband Robert, she exclaimed, “this is nothing but sheer racket. Brahms played it for me—not a single healthy idea, everything confused, no longer a clear harmonic sequence to be detected there! And now I still have to thank him—it’s really awful.” And the famed Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick gleefully added, “whoever has heard that, and finds it beautiful, is beyond help.” The work dates from 1853, and both Clara and Eduard might have been surprised that Liszt—the composer who openly told stories in music—had composed a work purely based on the interplay of abstract musical ideas.

Al Bertrand: Caricature of Franz Liszt, c. 1845

Specifically, Liszt binds his sonata via a process of thematic transformation, changing the character of musical themes while retaining their essential identity. And one such transformation appears in what commentators have called a “fugue of diabolical qualities.” Liszt intensely studied counterpoint and fugues, and he frequently uses these processes to represent struggle. The specific struggle represented in this fugal section, according to some scholars, seems to be between Liszt and Satan, with Liszt “struggling towards a higher plane.” Be that as it may, it certainly is a struggle for every pianist.

Franz Liszt: Piano Sonata in B minor, “Allegro energico” (Alfred Brendel, piano)

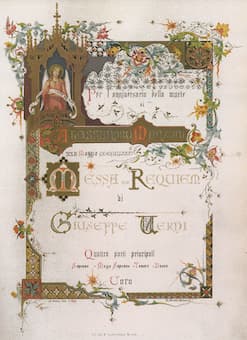

Verdi: Requiem

When Giuseppe Verdi started work on his Requiem in 1874, he was sixty-one years old and believed his career as a composer to be finished. The scale of his Requiem is operatic in scope, calling for a large orchestra, double choir, and four soloists. And not entirely unexpected, two of the movements contain fugues. Verdi clearly pays tribute to the past, but concurrently displays the ability to use old techniques in imaginative and new ways. While the fugal expositions unfold in a matter of fact manner, Verdi makes full use of the expressive power of the orchestra in the middle and closing sections. He skillfully pairs the instruments of the orchestra with certain voices, “allowing the orchestra to participate directly in the fugue and also distinguishing the choral lines by the addition of different instrumental timbres… This allows Verdi to work with a much broader canvas while maintaining the clarity of the texture.” It has been suggested that Verdi’s Requiem is an impassioned work, “displaying human emotion at its most serene and also at its most vulnerable.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Requiem, “Sanctus” (Svetoslav Obretenov National Philharmonic Choir; Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra; Emil Tabakov, cond.)

Otto Böhler: Bruckner caricature, 1897

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) was prone to suffer from devastating insecurities and debilitating periods of low self-esteem. At the age of thirty, he interrupted his compositional activities for a period of almost six years to immerse himself in a rigorous study of counterpoint and fugue under Simon Sechter. He began with general bass practice and progressed through species counterpoint to complex canon and fugue. On account of his extensive studies, Bruckner was able to succeed Sechter as professor of counterpoint at the Vienna Conservatory. Counterpoint and fugal processes had long been a feature of his compositions, and one commentator flippantly wrote, “The enemy blasphemes when the devout Brucknerite exclaims at the wonderful contrapuntal mastery of these devices. Technically they are remarkable only for their naïveté; the genius of them lies in the fact that they sound thoroughly romantic.” However, the fugal wonders he created in his Fifth Symphony do not support the notion of naiveté at all. “It was his hard-won technical maturity that allowed Bruckner to achieve one of the rarest forms of creative sophistication, artful and effective simplicity.” The exposition of the finale in Bruckner’s Fifth begins with a fugal exposition and ends with a chorale. That melody is then used in a second fugal exposition before both fugal subjects are used simultaneously.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 5, “Finale: Adagio-Allegro moderato” (Bavarian State Orchestra; Wolfgang Sawallisch, cond.)

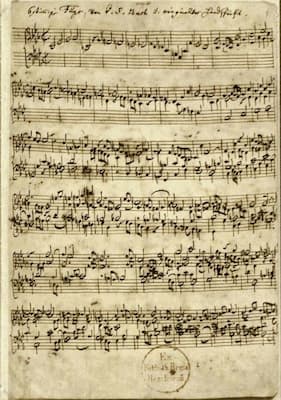

J.S. Bach: Musical Offering “Ricercar a 6”

When it comes to fugue and imitative counterpoint, I could go on forever. We haven’t even touched upon the glorious examples of counterpoint prevalent during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. There must be thousands of wonderful fugues written during the Baroque and the late Classical era. We only skimmed the uses of counterpoint and fugue during the 19th century, and merely dabbled in the twentieth-century when composers brought back fugues to a position of prominence. However, as we take gentle leave from this topic, why not go back where we started? The 19th century recognized that the learned counterpoint practiced by Johann Sebastian Bach was full of emotion. Bach taught us not only how to write music based on weaving together any number of independent voices to create a unity of constant change, “but also gave us the insight into the creative and emotional powers of the human mind.” Incapable of being expressed in words, it found its home in his music. As John Keats wrote:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter, therefore, ye soft pipes, play on:

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit dities of no tone…

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

J.S. Bach: Musical Offering, BWV 1079 “Ricercar a 6”