Buckle up for a musical marathon, as this blog will feature some of the longest piano pieces in the classical repertoire.

There are probably many reasons why composers craft such monumental work. It might be for a mix of artistic, philosophical, or even personal reasons. And there is always the possibility of a playful provocation or a satirical jab.

To be sure, the longest piano pieces in the classical repertoire are not for the faint of heart, and that includes performers and listeners. In the event, let’s get ready for some sprawling compositions that push the boundaries of what is possible on 88 keys.

I hope you will forgive me for only providing musical excerpts!

Erik Satie: Vexations

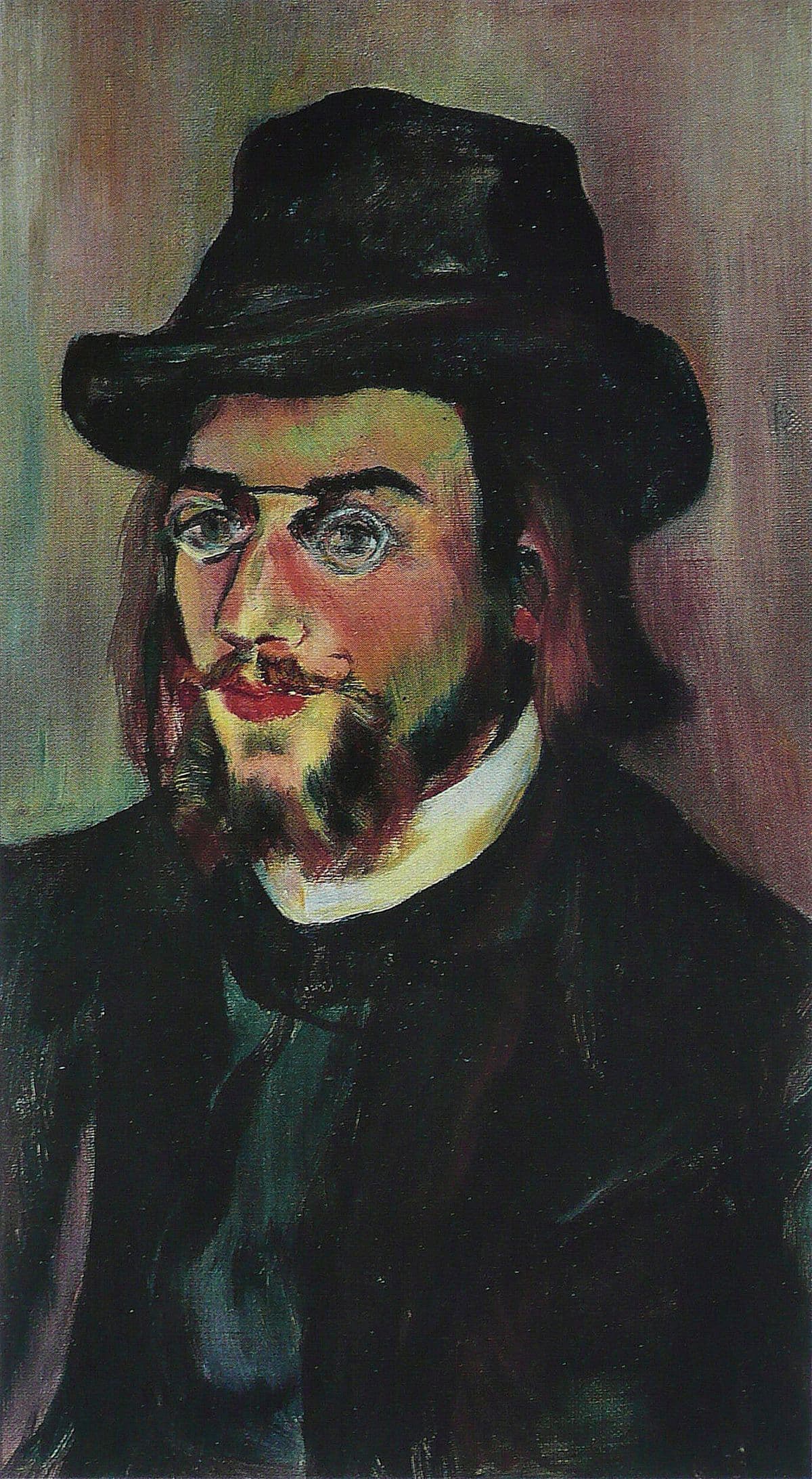

Suzanne Valadon’s portrait of Erik Satie

Erik Satie: Vexations (performance 1) (Noriko Ogawa, piano)

Erik Satie: Vexations (performances 2-6) (Noriko Ogawa, piano)

Erik Satie: Vexations (performances 7-11) (Noriko Ogawa, piano)

Erik Satie probably wrote his “Vexations” around 1893-1894. The piece consists of a short, hauntingly simple theme in the bass, presented four times in a specific sequence: first unaccompanied, then with chords above it, then unaccompanied again, and finally with a slightly varied harmonization.

It was written down on a single page, accompanied by a note from Satie that reads, “In order to play the motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.”

That’s pretty cryptic, if you ask me, and some scholars view it as a satirical jap at the grandiosity of composers like Wagner. It has been called “the poor man’s Ring des Nibelungen.” However, it might also be connected to his brief and intense affair with painter Suzanne Valadon in 1893.

We might never know for sure, but the first performance by a group of pianists, including John Cage, lasted 18 hours and 40 minutes. At the end, one audience member famously shouted “Encore!”

Frederic Rzewski: The Road

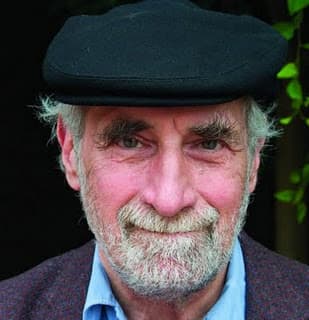

Frederic Rzewski

Frederic Rzewski: The Road – Part I: Turns (Frederic Rzewski, piano)

Satie’s Vexations, as the name and the instructions imply, is a rather repetitive composition. However, there are plenty of non-repetitive works on offer, somewhat limited by available recordings.

How about a monumental cycle that spans over 10 hours in performance by the American composer Frederic Rzewski. The Road was composed between 1995 and 2003, and is an expansive and ambitious work for solo piano by a composer known for his politically charged compositions.

The composer envisioned it as “a novel for piano,” like a literary epic by Tolstoy or Dostoevsky. The composition unfolds in 64 individual sections or “miles,” each representing a step along an imaginary journey.

Rzewski does offer some programmatic titles like “Stop the War,” and “A Walk in the Woods,” and he requires the performer to engage in unconventional actions, such as whistling, singing, shouting, stomping, and even delivering spoken commentary.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Symphonic Variations

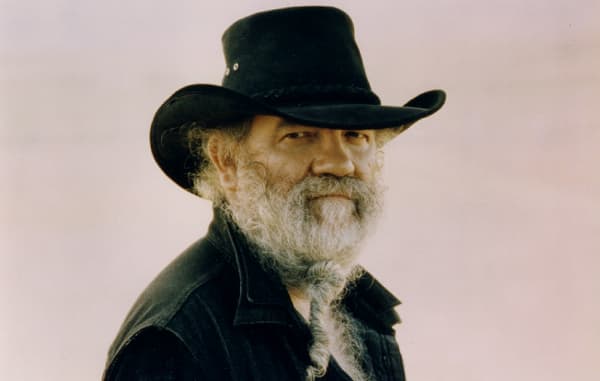

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Symphonic Variations, “Variation 56” (Michael Habermann, piano)

When dealing with the pursuit of dazzling difficulties of execution in works of mammoth dimension, the English-Parsi composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1894-1988) is in a league of his own.

His Symphonic Variations for Piano is a colossal solo piano work, estimated to last between 8.5 and 10.5 hours in performance, depending on tempo choices and breaks. It consists of 81 variations spread across three volumes, or “books,” each containing 27 variations, totalling 484 pages in its manuscript form.

The piece is based on an original theme, which Sorabji transforms through an astonishing array of styles, techniques, and moods. It ranges from lyrical and introspective to ferociously virtuosic and dense.

Variation No. 56 includes a free paraphrase from the finale of Chopin’s Sonata No. 2. It appears in long, accented tones as counterpoint to swift running passages. It’s a transformation rather than a transcription, as the texture grows to polychordal combinations at the climax.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: 100 Transcendental Studies

Sorabji’s 100 Transcendental Studies

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: 100 Transcendental Studies, Nos. 63-71 (Fredrik Ullén, piano)

Sorabji composed 90 hours of piano music during a 65-year period that began in 1917. His works are generally not well known because Sorabji banned public performances of his works from 1936 to 1976, citing his disillusionment with the musical world of his time and owing to his idiosyncratic personality.

His 100 Transcendental Studies date from 1940 to 1944, and they are the largest collection of concert etudes in the known repertoire. As the title suggests, they allude to Liszt’s famous set, but they also include influences from Scriabin, Busoni, and Godowsky.

The beginning of the cycle is a series of typical concert etudes that essentially explore a single technical or structural idea. Later in the set, Sorabji inserts pieces on a much larger scale.

Sorabji’s vast pianistic universe is compelling and strangely different from any other music before or after him. A performer who has tackled the complete set writes, “the 100 Transcendental Studies occupy a key position in the composer’s oeuvre.”

Alvin Curran: Inner Cities

Alvin Curran

Alvin Curran: Inner Cities 8 (Eve Egoyan, piano)

The American experimental composer Alvin Curran composed his cycle of 14 pieces titled “Inner Cities” between 1993 and 2013. It all started with a single piece and evolved into one of the longest non-repetitive piano compositions ever written.

Total duration exceeds six hours when performed in full, and individual sections are often dedicated to friends and influences like Lou Harrison and Trisha Brown.

We also find a vast range of styles, from minimalism, romanticism, avant-garde improvisation, and even jazz-inflected moments. For sure, Curran creates a sprawling sonic landscape.

The composer describes them as “contradictory etudes,” exploring liberation and attachment. Each piece unfolds from a single idea, becoming an immersive experience. They are often performed in settings where audiences can come and go, reflecting Curran’s rejection of traditional concert norms.

La Monte Young: The Well-Tuned Piano

La Monte Young is a minimalist and experimental composer, renowned for inventing innovative tuning systems and a hypnotic and expansive sound world.

He started his Well-Tuned Piano in 1964 and refined the work over the decades. It is an improvisatory solo piece performed in a tuning system devised by the composer.

La Monte Young

The piece typically lasts between 5 and 6 hours in performance, sometimes longer. It is divided into sections with evocative titles like “The Opening Chord ” and “The Magic Chord.” It’s less a fixed composition and more a living process.

The composer said, “it’s about tuning the nervous system to these pure intervals.”

Michael Finnissy: The History of Photography in Sound

Michael Finnissy’s The History of Photography in Sound

Michael Finnissy: The History of Photography in Sound, I “Le demon de’lanalogie” (Ian Pace, piano)

Let’s conclude this little survey with Michael Finnissy’s The History of Photography in Sound. It dates from between 1995 and 2001 and spans approximately 5.5 hours across 11 movements.

Each movement has a distinct title, like “North American Spirituals,” “Alkan-Paganini,” and “Etched Bright with Sunlight.” You can already tell that it reflects a vast tapestry of musical, cultural and personal references.

The piece isn’t a literal depiction of photography’s history but a metaphorical exploration of “photography in sound,” capturing moments, memories, and ideas through music. You certainly hear lots of quotations and allusions.

Summary

Classical Music’s longest piano journeys is a fascinating testament to human ambition, endurance, and the boundless possibilities of musical expression. They certainly push the boundaries of what a single performer can achieve.

The compositional approaches are wonderfully diverse, and each of the featured pieces demands not just technical mastery but an almost superhuman stamina from the pianist and an equally committed listener.

There are still plenty of monumental pieces for solo piano that have not been recorded or performed. A number of Sorabji compositions exceeding 4 hours or more are still undiscovered.

I don’t know if “Beatus Vir” by Jacob Mashak, with a duration of 11 hours, has ever been recorded, but the 12.5 hours work by Maurice Verheul titled “Alida No. 16f—La conscience totale” is still practically unknown.

And there is a work simply titled “For Clive Barker” by Matthew Lee Knowles that has a supposed duration of 26 hours! What wonderful musical frontiers where imagination outpaces practicality.

We certainly have to marvel at the audacity of composers who dared to dream in such vast, uncharted temporal expanses.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji: Opus Clavicembalisticum, “Pars Altera” (Geoffrey Douglas Madge, piano)