Max Bruch: Symphony No. 1 in E-flat Major, Op. 28

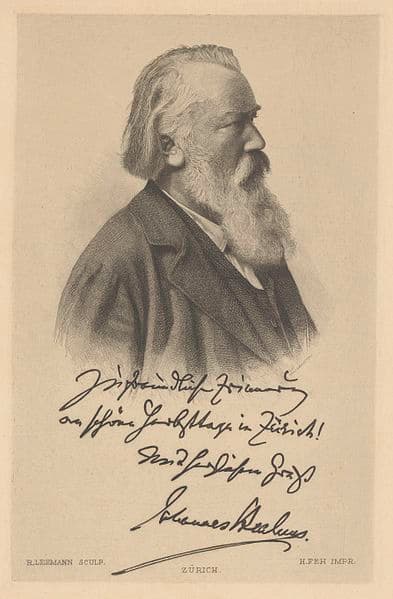

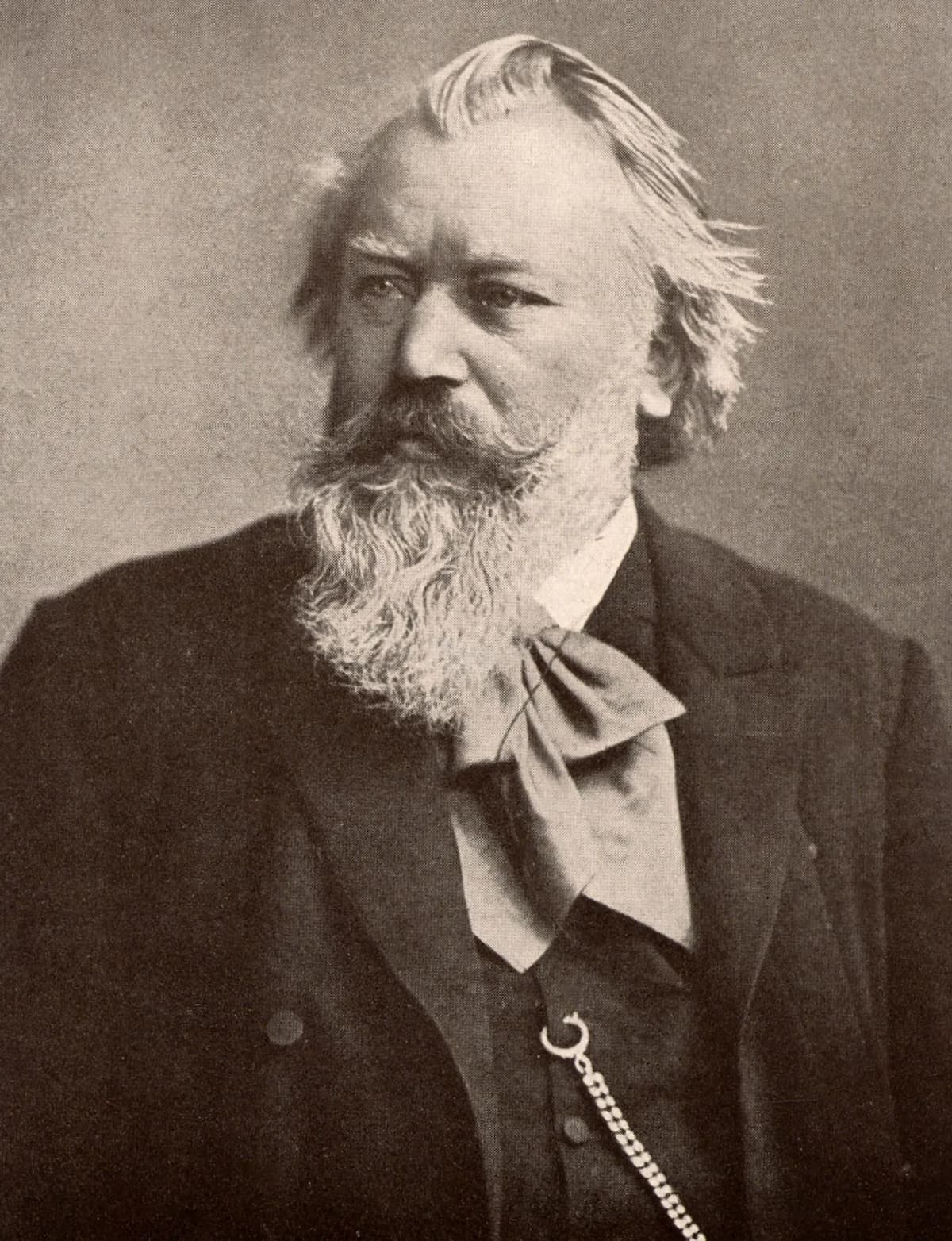

It has been said that Johannes Brahms and Max Bruch (1838-1920) enjoyed a long but superficially cordial relationship. Actually, Bruch considers Brahms “an arrogant and disagreeable man, liable to react to any overtures of friendship in a sarcastic fashion.” It has been suggested that Bruch’s antagonistic feelings toward Brahms were probably also due, to some extent, to professional jealousy. Bruch does seem to have held many Brahms compositions in high esteem, but he was not at all impressed by his symphonies. For example, Bruch confided in a friend “I have not so far managed to raise myself to such cultural heights and am for the time being dull-witted enough to find a quite extraordinarily great difference between Brahms’ symphonies and those of Beethoven.”

Johannes Brahms

And after conducting the Brahms 3rd in Breslau, Bruch wrote, “It contains much that is beautiful, but also much that lacks originality. As for the orchestration, all I can say is that the rest of us would deserve to be hanged if we orchestrated so wretchedly.”

Max Bruch

Little is known about Brahms’ opinion of Bruch, the composer, but he seems to have been impressed by some early works. In one of his letters, Brahms seemingly complemented Bruch on “being such an industrious and productive composer, noting with great pleasure and some envy.” As usual, the underlying current of veiled sarcasm would immediately have been apparent to Bruch. When Brahms got to know the Bruch oratorio Moses in 1895, he wrote to Clara Schumann. “It filled one with great gratitude towards God for having preserved one from the sin, vice, or bad habit of simply putting notes on paper.” In 1860, both Bruch and Brahms were signatories to the manifesto against the “New German School,” and in 1868, Bruch dedicated his First Symphony to Brahms. We do not know Brahms’ reaction to the work or how much he learned in terms of orchestration.

Albert Dietrich: Symphony in D minor, Op. 20

Albert Dietrich

Albert Dietrich: Symphony in D minor, Op. 20 (Oldenburg State Orchestra; Alexander Rumpf, cond.)

Contrary to Max Bruch, Albert Dietrich (1829-1908) was a great personal friend of Brahms. In fact, Brahms was one of three composers Dietrich championed throughout his life, the others being Bach and Schumann. Dietrich first met Brahms in Düsseldorf in 1853 and wrote to a friend. “Genius is written all over his face and shines out of his bright blue eyes.” Dietrich, Schumann and Brahms even collaborated on the “F-A-E” (Frei aber einsam, Free but lonely) violin sonata in honour of Joseph Joachim. Brahms and Dietrich met frequently over the years, and they corresponded on a regular basis. The closeness of the friendship is also demonstrated by the fact that Brahms was the godfather of Dietrich’s first child, Max. No matter the closeness, however, Brahms was a stern critic when it came to Dietrich’s compositions. In a letter to Clara Schumann in October 1868, he warned her “that she would be hearing a symphony by Dietrich during her forthcoming visit to Oldenburg and cautioned her to be diplomatic rather than frank in her reaction.” That particular Symphony in D minor would subsequently be dedicated to Brahms.

In 1897, Dietrich published his “Recollections of Johannes Brahms,” providing detailed insights into the composer’s personality and character. As he writes, “The appearance, as original as interesting, of the youthful, almost boyish-looking musician, with his high-pitched voice and long fair hair, made a most attractive impression upon me. I was particularly struck by the characteristic energy of the mouth and the serious depths in his blue eyes.” Apparently, at that time, Brahms told Dietrich that he liked to think of the words of folksongs, as they seemed to suggest musical themes to his mind. “Brahms was asked to play and executed Bach’s Toccata in F major and his own Scherzo in E flat minor with wonderful power and mastery. Bending his head down over the keys and, as was his wont in his excitement, hummed the melody aloud as he played. He modestly deprecated the torrent of praise with which his performance was greeted. Everyone marvelled at his remarkable talent, and, above all, we young musicians were unanimous in our enthusiastic admiration of the supremely artistic qualities.” According to Dietrich, “Brahms never spoke of the works on which he was engaged, neither did he publicly make plans for future compositions,” and he “was most at ease in a striped flannel shirt, without either tie or stiff collar; even his soft felt hat was more often carried in his hand than worn on his head.”

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: String Quartet in G minor, Op. 42

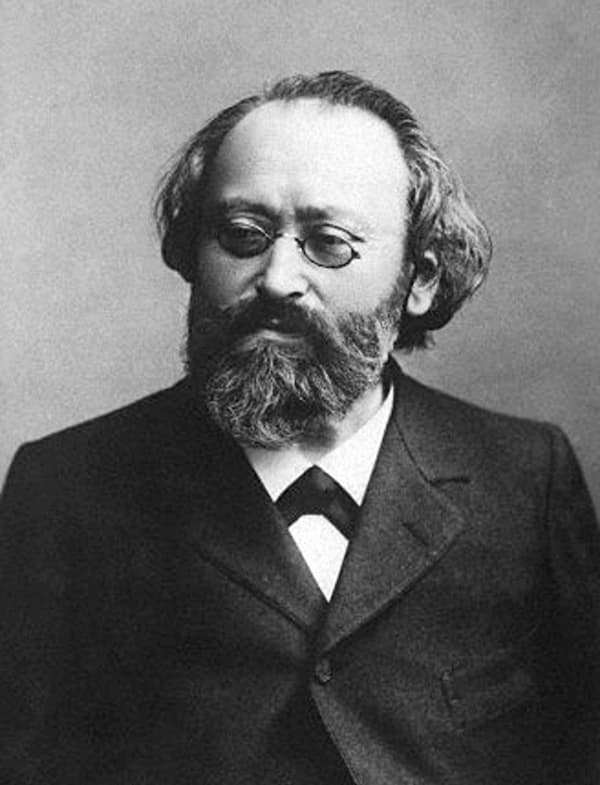

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: String Quartet in G minor, Op. 42 No. 1 (Minguet Quartet)

In a previous episode on chamber music dedicated to Brahms, we met in Heinrich von Herzogenberg, one of the most enthusiastic admirers of Johannes Brahms and his music. However, the dedication of three complete string quartets under a single opus number remains unique. It all started in December 1876, when a Berlin critic wrote a review that juxtaposed the premieres of Brahms’ Op. 67 and Heinrich von Herzogenberg’s Op. 18 string quartets. He writes, “A manuscript quartet by Brahms was performed by Joachim and his associates that certainly would not have been regarded by public or critic as anything other than a failed work. The author of this review, a very enthusiastic admirer of Brahms from long ago—listened in vain to find ten measures that allowed him to recognise the composer.” And describing the third evening, “Joachim performed a quartet by Herr von Herzogenberg, a composer who is still almost unknown here but who enjoys a good reputation in Leipzig. The principal themes are original, truly warm and melodically fluid… Hopefully, we will meet the composer again soon.”

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: String Quartet in D minor, Op. 42 No. 2 (Minguet Quartet)

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg

Brahms wasn’t particularly happy, and neither was Heinrich’s wife, Elisabeth. At dinner with the Herzogenbergs, Brahms ridiculed the critic for denigrating his Op. 67 in favour of Heinrich’s Op. 18. Elisabeth took Brahms to task for his tactlessness in a letter, “I believe and hope that we are on such terms that one may allow oneself not only pastry jokes but also, once in a while, an honest word… Heinrich, who does not feel worthy to untie your shoelace, a seeking, learning, submissive man who is a hundred times more bothered by a foolish overestimation than by the most scathing criticism because he can learn absolutely nothing from the former.” In the event, Heinrich was asked to mail a copy of his Op. 18 to Brahms, who responded, “Already upon quick review, it gave me great pleasure, and this evening it will make a cosy hour for me.” And at a meeting later that summer, Brahms did once again comment on Herzogenberg’s music. We don’t know what was said, but Elisabeth writes, “You were so good for my Heinz, and now he sits and reflects, bent over his quartet paper, and thinks to himself, as he forms new note-tails for theme and variations, that a word from the mouth of John the Baptist is worth more than a hundred essays on ‘the style in which we should compose,’ even if God himself wrote them.”

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: String Quartet in G Major, Op. 42 No. 3 (Minguet Quartet)

As Elisabeth reports, Heinrich was hard at work on another string quartet, but it did not appear in print until 1884, when he released a set of three as his Op. 42 and dedicated them all “to his highly esteemed friend Johannes Brahms.” These new compositions appear to be closely aligned with the “strict aesthetic, which Brahms had advocated privately.” Brahms did take note, and upon receiving a copy of Op. 42, he declared them “Heinrich’s best compositions to date.” He even referred to Op. 42 as “your-our quartet No. 1.” As a scholar writes, “Brahms’ status as dedicatee for Op. 42 surely helps to explain the sense of ownership reflected in his strangely blended pronouns. But perhaps his diction also conveyed an awareness that his own advice had influenced this particular piece in some way.” In August 1891, Clara Schumann informed Brahms that Elisabeth von Herzogenberg was suffering from a terminal heart disease. When she died in 1892, Brahms’ friendship with Heinrich and engagement with his music evaporated almost entirely. It has been suggested “that Elisabeth’s diplomacy turned out to have been essential in maintaining even the fraught and flawed relationship that still existed among the three musicians in 1891.” Essentially, Elisabeth had forced Brahms to treat Heinrich’s music seriously.

Vincenz Lachner: 12 Ländler with Intermezzo and Finale

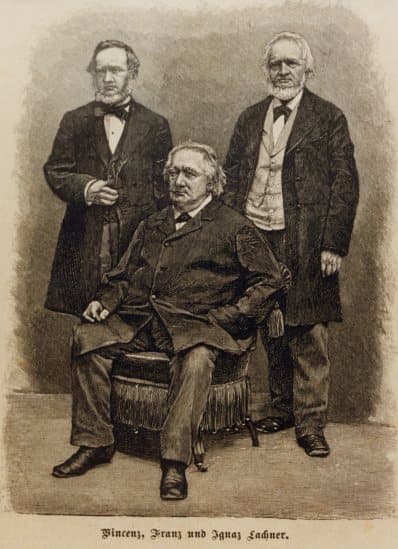

The Lachner Brothers

Vincenz Lachner: 12 Ländler with Intermezzo and Finale (Sontraud Speidel, piano)

The German composer and conductor Vincenz Lachner (1811-1893) was the younger brother of Franz Lachner, known as a close friend of Franz Schubert. While Vincenz considered the musical trends set by Liszt and Wagner as aberrations, he was simultaneously “puzzled and displeased by certain aspects of Brahms’ musical aesthetic.” As he wrote to his former student Hermann Levi, “I must confess to you that much in his music appears ugly, bizarre, and exaggerated to me, and I cannot comprehend why he, who is such a tremendous harmonist, so frequently and so deliberately offends against tonal beauty. Indeed, I consider that in the creation of noble and beautiful thoughts directly impacting on our sensations, which, in my view, is the highest and supreme task for the artist and the very touchstone of genius, he comes off quite poorly.” Lachner was not shy in sharing his opinions with Brahms, and he wrote at length on the subject of the Brahms Second Symphony in August 1879. His focus fell on the opening movement, “in which he found countless features worthy of the deepest admiration.”

However, he also voiced certain objections, particularly against the sudden injection of darker elements into the prevailing ambience of radiant sunshine. He writes, “Why do you throw the angry drum roll and the gloomy, lugubrious sounds of the trombones and tubas into the idyllically serene mood created at the beginning of the first movement?” Brahms replied in a letter headed, “My very dear friend.” He then goes on to stoutly defend his use of instruments in question, as well as the other musical solutions he had adopted. Addressing the contamination of the sunny atmosphere, he writes, “I am a deeply melancholy person, constantly aware of the black wings flapping above the heads of all men.” Be that as it may, Lachner’s sunny 12 Ländler with Intermezzo and Finale are dedicated to Brahms.

Niccoló van Westerhout: Piano Sonata in F minor

Niccoló van Westerhout

Niccoló van Westerhout: Piano Sonata in F minor (Pierliugi Camicia, piano)

Niccoló van Westerhout (1857-1898) was born in Puglia into a musical family of Dutch origin, and he trained at the Conservatory at Naples. He was well known as a pianist, and as a composer he tried his hands at a Symphony, a Violin Concerto and an opera. However, he is probably best known for his large number of songs and piano pieces linked to the fashionable salon taste. His Sonata in F minor is a highly complex and ambitious work dedicated to Johannes Brahms. A scholar writes, “The dedication to Brahms is to be regarded as an exception insofar as on the one hand there is no direct acquaintance between Brahms and Westerhout, and on the other hand he is by far the best well-known of the dedicatees.” In addition, the Brahms dedication also discloses that Brahms did play a role in the musical life of Italy, especially within the framework of certain genres being taught in Conservatories around the country. Westerhout clearly disclosed his affinity to Brahms in a letter to a friend, where he writes, “I am not an innovator, because these words have no common sense in art: I am proud to continue a venerated tradition.”

Robert Schumann: Des Sängers Fluch, Op. 139

Ludwig Uhland

Let us conclude this series of works dedicated to Brahms by returning to Robert Schumann and his setting of Des Sängers Fluch (The Minstrel’s Curse). As a choir conductor in Düsseldorf, Schumann composed three large-scale choral ballads to epic poems by Ludwig Uhland, all accompanied by a full orchestra. “The Minstrel’s Curse” tells the story of two medieval minstrels, one young and one old, who sing so well at a court that the courtiers stop their fighting, and the Queen casts a rose from the breast to their feet. In a fit of jealous rage, the King kills the younger singer. The older minstrel, actually the victim’s father, receives the body of his murdered son. He curses the King, whose reign will fail and whose name will always be associated with the events described. Schumann composed his setting in 1852 within a network of middle-class amateur choral societies, glee clubs, and semi-professional orchestras. Dedicated to Johannes Brahms, Des Sängers Fluch undoubtedly helped to spawn the Brahms choral ballad settings Rinaldo, Schicksalslied, and the Alto Rhapsody. While Brahms’ settings, at least partially, have retained relevance in the concert hall, the entire “genre suffered from the social upheavals of the modern age, and much superior music of the romantic age was consigned to oblivion and still awaits rediscovery.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter