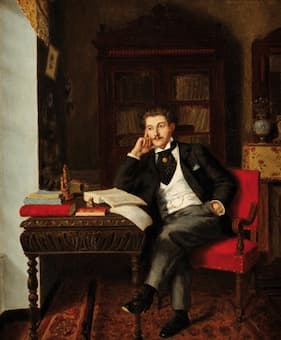

Presumed portrait of Marcel Proust, 1899

Marcel Proust’s oeuvre is rife with musical references. He openly refers to composers, librettists, performers and musical compositions. One anecdote reports that Proust woke up Gaston Poulet, the leader of the Poulet Quartet, in the middle of the night. The poet requested that the violinist assemble his Quartet to play the Franck String Quartet in D major in the early hours one morning. It is said that Proust transported the four musicians by cab to his boulevard Haussmann flat, “where for handsome remuneration, the chamber group played the piece twice.”

102 boulevard Haussmann – Marcel Proust lived here after his parents died between 1906 and 1919.

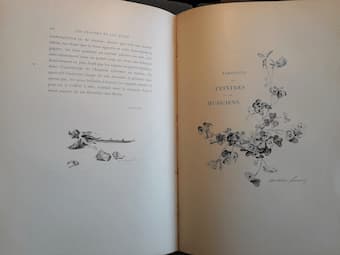

Music played an important part in expanding and enriching the “range of his own literary language through figure and allusion.” But what is more, he was acutely interested in the power of music to trigger involuntary memories. Proust granted music a pivotal role in a work of literature. “His vision of the potential unity and transformative power of the arts… shaped the European modernist tradition that followed him.” A leading literary critic writes, “Music as performance, as topic of debate, as catalyst of memory, emotion, and desire, plays an obbligato accompaniment to the interpersonal drama of the Proustian social world: its hilarity, its pathos, its vacuity, its sensuality, its cruelty.” In his four poem “Portraits de peintres,” Proust paid homage to four painters whose works he had admired in the Louvre. These poems on painters were followed up by four “Portraits de musiciens,” Chopin, Gluck, Schumann and Mozart.

César Franck: String Quartet in D Major (Academica String Quartet)

Proust’s Portraits de peintres et de musiciens

In his early years, Proust penned texts on narrative theory, articles on fashion, music hall singers, and salons. Some of his early poetry in regular verse offers portraits of artists and musicians. In each poem the poet directly addresses himself to an individual artist. “Proust borrows this rhetorical stance from Baudelaire’s poem ‘Les Phares,’ in which the poet addresses himself to artists, painters, and musicians.” In his first musician portrait, the poet is approaching Chopin. The poem agitates a sea of emotion, and “the composer becomes a sea of sighs. His name becomes a metaphor for a world of antithetical emotions that characterize Chopin’s musical compositions.”

Chopin

Chopin, mer de soupirs, de larmes, de sanglots | Chopin, sea of sighs, tears, sobs |

Qu’un vol de papillons sans se poser traverse | That a flight of butterflies without landing crosses |

Jouant sur la tristesse ou dansant sur les flots. | Playing on sadness or dancing on the waves. |

Rêve, aime, souffre, crie, apaise, charme ou berce, | Dream, love, suffer, cry, soothe, charm or rock, |

Toujours tu fais courir entre chaque douleur | Always you make it run between each pain |

L’oubli vertigineux et doux de ton caprice | The dizzying and sweet forgetfulness of your whim |

Comme les papillons volent de fleur en fleur; | As butterflies fly from flower to flower; |

De ton chagrin alors ta joie est la complice: | Of your grief then your joy is the accomplice: |

L’ardeur du tourbillon accroît la soif des pleurs. | The ardor of the whirlwind increases the thirst for tears. |

De la lune et des eaux pâle et doux camarade, | Of the moon and waters pale and gentle comrade, |

Prince du désespoir ou grand seigneur trahi, | Prince of despair or great lord betrayed, |

Tu t’exaltes encore, plus beau d’être pâli, | You are still excited, more beautiful to be pale, |

Du soleil inondant ta chambre de malade | Sun flooding your sick room |

Qui pleure à lui sourire et souffre de le voir… | Who weeps to smile at him and suffers to see him … |

Sourire du regret et larmes de l’Espoir! | Smile of regret and tears of Hope! |

Frédéric Chopin: Etude No. 3 in E, Op. 10/3, “Tristesse” (Lang Lang, piano)

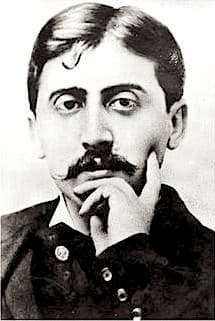

Marcel Proust, 1900

Proust, as we have seen, would actually pay musicians to play cherished pieces in his sleeping quarters as he lay in bed. He had a keen interest in Chopin, and Proust used the composer as a vehicle for a range of aesthetic-moral considerations. Proust was closely aligned with the salons of the belle époque, and since he was not a musician, his vision is one of a gifted and scrupulous listener. The Chopin portrait creates opposing metaphors, as the composer is both smile and tears. For Proust, “Chopin lies sick in a room inundated with sunshine.

Gluck

Temple à l’amour, à l’amitié, temple au courage | Temple of love, of friendship, temple of courage |

Qu’une marquise a fait élever dans son parc | That a marchioness had erected in her park |

Anglais, où maint amour Watteau bandant son arc | English, where many love Watteau bending his bow |

Prend des cœurs glorieux pour cibles de sa rage. | Targets glorious hearts in his rage. |

Mais l’artiste allemand – qu’elle eût rêvé de Cnide! | But the German artist – how much she dreamed of Cnidus! |

Plus grave et plus profond sculpta sans mignardise | More serious and deeper sculpted without cuteness |

Les amants et les dieux que tu vois sur la frise : | The lovers and the gods you see on the frieze: |

Hercule a son bûcher dans les jardins d’Armide! | Hercules has his pyre in the gardens of Armida! |

Les talons en dansant ne frappent plus l’allée | Heels while dancing no longer hit the aisle |

Où la cendre des yeux et du sourire éteints | Where the ashes of faded eyes and smiles |

Assourdit nos pas lents et bleuit les lointains ; | Muffles our slow steps and blues the distance; |

La voix des clavecins s’est tue ou s’est fêlée. | The voice of the harpsichords is silent or cracked. |

Mais votre cri muet, Admète, Iphigénie, | But your silent cry, Admète, Iphigénie, |

Nous terrifie encore, proféré par un geste | Still terrifies us, uttered by a gesture |

Et, fléchi par Orphée ou bravé par Alceste, | And, bent by Orpheus or defied by Alceste, |

Le Styx, – sans mâts ni ciel, – où mouilla ton génie. | The Styx, – without masts or sky, – where your genius anchored. |

Gluck aussi comme Alceste a vaincu par l’Amour | Gluck also as Alceste conquered by Love |

La mort inévitable aux caprices d’un âge; | Death inevitable at the whims of an age; |

Il est debout, auguste temple du courage, | He is standing, august temple of courage, |

Sur les ruines du petit temple à l’Amour. | On the ruins of the little temple of Love. |

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Armide, “Enfin, il est ma puissance” (Karina Gauvin, soprano; Pacific Baroque Orchestra; Alexander Weimann, cond.)

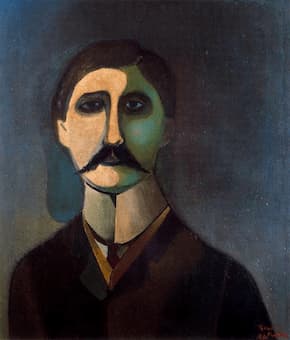

Marcel Proust © Richard Lindner

Christoph Willibald Gluck revolutionized opera in the 18th century, and Proust refers to several of Gluck’s operas in his poem. He hears Gluck sculpting a world capable of overcoming death. As such, “Gluck himself stands metaphorically as the temple of courage, on the ruins of the small temple of love.” For Proust, opera was allied with classical literature, and an artistic monument enduring against time. It has been suggested that this affirmation is “perhaps a young writer’s optimistic version of the eternal nature of art that one finds ironically portrayed In Search of Lost Time. Proust’s enigmatic portrait of Robert Schumann makes ample reference to a number of lieder and compositions in order to portray the contradiction between “successful compositions and the composer’s mental anguish.”

Schumann

Du vieux jardin dont l’amitié t’a bien reçu, | From the old garden whose friendship has received you well, |

Entends garçons et nids qui sifflent dans les haies, | Hear boys and nests whistling in the hedges, |

Amoureux las de tant d’étapes et de plaies, | Lovers weary of so many stages and wounds, |

Schumann, soldat songeur que la guerre a déçu. | Schumann, a pensive soldier disappointed by the war. |

La brise heureuse imprègne, où passent des colombes, | The happy breeze permeates, where doves pass, |

De l’odeur du jasmin l’ombre du grand noyer, | From the scent of jasmine the shadow of the large walnut tree, |

L’enfant lit l’avenir aux flammes du foyer, | The child reads the future in the flames of the hearth, |

Le nuage ou le vent parle à ton cœur des tombes. | The cloud or the wind speaks to your heart of the graves. |

Jadis tes pleurs coulaient aux cris du carnaval | Once your tears flowed to the cries of the carnival |

Ou mêlaient leur douceur à l’amère victoire | Where their sweetness mingled with the bitter victory |

Dont l’élan fou frémit encore dans ta mémoire; | Whose mad impulse still quivers in your memory; |

Tu peux pleurer sans fin: Elle est à ton rival. | You can cry endlessly: She’s your rival. |

Vers Cologne le Rhin roule ses eaux sacrées. | Towards Cologne the Rhine rolls its sacred waters. |

Ah! que gaiement les jours de fête sur ses bords | Ah! that cheerfully on feast days on its shores |

Vous chantiez! – Mais brisé de chagrin, tu t’endors… | You were singing ! – But broken with grief, you fall asleep … |

Il pleut des pleurs dans des ténèbres éclairées. | It is raining tears in illuminated darkness. |

Rêve où la morte vit, où l’ingrate a ta foi, | Dream where the dead woman lives, where the ungrateful has your faith, |

Tes espoirs sont en fleurs et son crime est en poudre… | Your hopes are in bloom and his crime is in powder … |

Puis éclair déchirant du réveil, où la foudre | Then heartbreaking flash of awakening, where lightning |

Te frappe de nouveau pour la première fois. | Hit you again for the first time. |

Robert Schumann: Kinderszenen

Mozart

Italienne aux bras d’un Prince de Bavière | Italian in the arms of a Prince of Bavaria |

Dont l’œil triste et glacé s’enchante à sa langueur! | Whose sad and frozen eye is enchanted by its languor! |

Dans ses jardins frileux il tient contre son cœur | In his chilly gardens he holds against his heart |

Ses seins mûris à l’ombre, où têter la lumière. | Her breasts ripened in the shade, where to nurse the light. |

Sa tendre âme allemande, – un si profond soupir! – | Her tender German soul – such a deep sigh! – |

Goûte enfin la paresse ardente d’être aimée, | Finally taste the ardent laziness of being loved, |

Il livre aux mains trop faibles pour le retenir | He delivers to hands too weak to hold him back |

Le rayonnant espoir de sa tête charmée. | The radiant hope of his charmed head. |

Chérubin, Don Juan ! loin de l’oubli qui fane | Cherub, Don Juan! far from fading oblivion |

Debout dans les parfums tant il foula de fleurs | Standing in the perfumes he trod with so many flowers |

Que le vent dispersa sans en sécher les pleurs | That the wind dispersed without drying the tears |

Des jardins andalous aux tombes de Toscane ! | From Andalusian gardens to Tuscan tombs! |

Dans le parc allemand où brument les ennuis, | In the German park where trouble haunts, |

L’Italienne encore est reine de la nuit. | The Italian is still queen of the night. |

Son haleine y fait l’air doux et spirituel | His breath makes it look sweet and spiritual |

Et sa Flûte enchantée égoutte avec amour | And his Magic Flute drips with love |

Dans l’ombre chaude encore des adieux d’un beau jour | In the warm shadow still goodbyes of a beautiful day |

La fraîcheur des sorbets, des baisers et du ciel. | The freshness of sorbets, kisses and the sky. |

The tomb of Marcel Proust at Père Lachaise Cemetery,

Paris, France

The poetic portrait of Mozart is set in a landscape in which an Italian woman strolls on the arm of a Bavarian prince. The prince succumbs to love as the poem evokes characters from the Mozart opera The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni. Since nostalgia of paradise is an important motif throughout Proust’s work, these opera are set in the gardens of Andalusia and Tuscany. Towards the end of the poem, the Italian woman turns out to be the Queen of the Night, “who now uses her flute to create an earthly paradise uniting the freshness of sorbets, kisses, and heaven.” Proust conjures a world in which Mozart’s operas unite the supposed opposite worlds of German and Italian culture, unfolding in a garden of paradise. Tellingly, access to this paradise of reconciliation is to be found in the works of art.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: The Magic Flute, K. 620 “Overture” (Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra; Karl Böhm, cond.)