“My music is best understood by children and animals”

Igor Stravinsky, 1920s

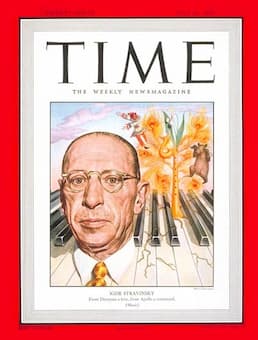

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) graced the cover of Time Magazine in 1948. The supporting article described him as a “Master Mechanic,” a man to be hired, on his terms, to write music on order. This seems a rather narrow focus for a composer widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the 20th century. But it does hint at the stylistic diversity and artistic unity and integrity that always were fundamental elements of his creative force. In musical terms, he might well have represented the face of an entire century as his works touch almost every important trend and tendency the century had on offer. Born in Oranienbaum, a small settlement near St. Petersburg in 1882, Stravinsky’s father was an opera singer who expected his son to study law. Igor had taken to music at an early age and was an accomplished pianist by the age of fifteen. Bored with his studies at the University of Saint Petersburg, he began to take private lessons with Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, who would turn out to be his greatest musical influence.

Igor Stravinsky: Scherzo fantastique, Op. 3 (Sydney Symphony Orchestra; Edo de Waart, cond.)

Stravinsky, 1903

Taking his inspiration from Russia’s beautifully expressive folk music, Stravinsky introduced himself to the public as a composer in 1909 in Saint Petersburg, with Sergei Diaghilev in the audience. The director of the famed “Ballets Russes” active in Paris invited Stravinsky to compose music for a Russian fairy tale centering on a magically glowing bird. The Firebird not only established Stravinsky’s international fame, but also marked the beginning of the collaborations with Diaghilev, who eventually also produced Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. Clothed in colorful and fantastic orchestration Stravinsky’s folk-song melodies are subject to primitive rhythmic drives, unmistakably announcing that Modernism had arrived in music. Stravinsky and his family spend their summers in Russia and winters in Switzerland until 1914. Unfit for military service due to health reasons, they moved to the shores of Lake Geneva. Financially struggling, Stravinsky managed to attract some private sponsorship, and he left behind the lavish grandeur of his famous Ballets. Abandoning large orchestral forces, he began to prefer chamber and choral ensembles, and the solo piano. In 1920, the family once more packed their bags and moved to France.

Igor Stravinsky, drawn by Pablo Picasso, 31 Dec 1920

Stravinsky’s switch to a smaller, more intimate orchestration coincided with a transformation of his musical conception and language. He replaced the exaggerated gestures of late Romanticism and the expressive indulgences of the recent past, with works that revived the balance and clearly perceptible thematic processes of earlier musical styles. Stravinsky set out his formalist ideas in an article published in 1924, and he embarked on a number of instrumental works that took the high-classical German tradition as a model. He adopted classical forms and procedure like sonata, variation, and fugue, and his Octet is generally regarded as the start of neo-classicism in his music. Stravinsky, not for the last time in his career, had reinvented himself and essentially embarked on a new career that paid homage to the great European tradition. Stravinsky first visited the United States in 1930, but in 1935 embarked on a coast-to-coast concert tour of the country. He visited South America the following year, spending seven weeks conducting concerts in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro. Additional tours to the United States took place in subsequent years, and with the war machinery in Europe gathering steam, Stravinsky accepted the Chairmanship of Poetry at Harvard University.

Stravinsky on Time Magazine cover, 1948

© Boris Chaliapin

For Stravinsky, the move to America was his second emigration. He only spoke primitive English and moved largely in émigré circles. Moving to California, he dabbled in film music as his cultural thinking transformed from its focus on Russian and French influences towards the Anglo-Saxon view of life he encountered in America. In 1949, the philosopher Theodor Adorno described Igor Stravinsky as a “dummy civil servant, psychotic, infantile and devoted to making money.” At issue was the composer’s predilection for drawing musical inspiration from centuries past, simply recasting themes from Pergolesi to Mozart.

Stravinsky, 1965

Unsurprisingly, Stravinsky musically reinvented himself anew. While adapting the melodic styles of earlier eras, he now experimented with virtually every technique of 20th century music. And that included polytonality and 12-tone serialism. He completed his last major work, the Requiem Canticles in 1966, and he died of heart failure in New York, fifty years ago, on 6 April 1971. Stravinsky was generally ignored in the period following his death, but today we understand his artistic achievements as the result of his multiple exiles. While he stayed deeply connected to his native musical soil, “he cultivated a flexible and reciprocal association with his changing environments… He continuously allowed his sensibilities to be fed, even transformed, by the music and music-making of others.” Stravinsky, as he articulated in his “Memories and Commentaries,” wanted to be influenced.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Requiem Canticles (Gregg Smith Singers; Ithaca College Concert Choir; Columbia Symphony Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)

Your Newsletter is always so interesting, thank you. I wonder if you would consider writing about the wonderful and almost forgotten Italian pianist, Sergio Fiorentino.

Excellent suggestion!

Thank you Margaret.