Dante gazes at Mount Purgatory in an allegorical portrait

by Agnolo Bronzino, painted c. 1530

Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy” contains 14, 233 lines of text divided into three main sections, “Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise.” As we might well imagine, there isn’t much music in Hell. It reverberates with “sighs, screams and lamentations, and different tongues make not sweet harmony but an eternal tumult in the dark air.” In contrast, music does play an important role in Purgatory, “as on every terrace the souls sing an appropriate hymn or antiphon from the liturgy.” Literary scholars have suggested that Dante emphasizes the “therapeutic power of music, sung as an act of corporate worship and as part of a rite of expiation.” It is only in the heavens that music “conveys the order, beauty and bliss of eternal beatitude and perfect love.” Dante suggests in poetry the impact of great music on the listeners, but no contemporary settings of Dante’s poetry have survived. The earliest surviving settings of Dante’s poetry emerge only in the first part of the 16th century.

Luca Marenzio: “Cosi nel mio parlar voglio esser aspro” (I wish my speech to be as harsh) (Concerto Italiano; Rinaldo Alessandrini, cond.)

Illustration of Lucifer in the first fully illustrated print edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Dante did comment on the relationship of poetry and music, suggesting, “Poetry is simply a work of imagination composed or made according to the rules of rhetoric and music.” In essence, the musical organization of words is the distinguishing factor between poetry and prose. While a handful of madrigal settings of Dante do survive, the poet was, during the sixteenth century, completely overshadowed by Petrarch. Only at the onset of the Romantic period did composers begin to respond to the pathos of certain scenes. At the height of his career in November 1847, Franz Liszt surprisingly retired from the concert stage. He had long wanted to leave the world of virtuoso transcriptions and paraphrases behind, and he was looking to explore new directions in music. Returning to Germany, he focused on the works of Beethoven and his reading of “The Divine Comedy” inspired thoughts about Classical form. Liszt began to revise earlier compositions based on Dante, and the resulting “Après une lecture du Dante, Fantasia quasi Sonata” takes its title from a poem by Victor Hugo.

Franz Liszt: Annees de pelerinage, Italy, No. 7 “Apres une lecture du Dante” (Vittorio Bresciani, piano)

Dante and His Poem by Domenico di Michelino

Liszt’s most famous reading of Dante, which we featured in our previous article, emerged in his “Dante Symphony.” Liszt wrote to Wagner in 1855, “I have long been toying with the idea of a Dante Symphony. I hope to finish it in the course of this year. Three movements altogether; Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. The first two purely instrumental, the last with chorus.” Wagner was not convinced, and Liszt eventually concluded the work with a setting for women’s voices. The work was dedicated to Wagner, and it inspired the Italian composer Giovanni Pacini (1796-1867), who is probably best known for his operas, to compose a “Sinfonia Dante” in 1865. That composition aligned with the sixth centenary of Dante’s birth, and it was first heard in Florence. Pacini’s colleague Saverio Mercadante wrote to the composer, “I had the Symphony played several times on the piano and, much to my satisfaction, I had to admire the magnificence of the score, its beautiful forms and its fresh and charming ideas. I find it a work worthy both of its author and the subject it aims to express.”

Giovanni Pacini: Sinfonia Dante (Teatro del Giglio di Lucca Orchestra; Gianfranco Cosmi, cond.)

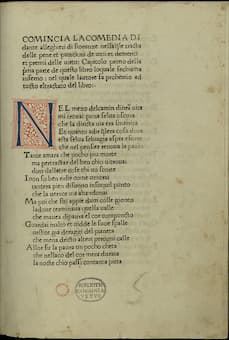

Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy” First printed edition, 1472

Enrique Granados (1867-1916) premiered his narrative symphonic poem “Dante” in Barcelona in June 1908. The work focuses on two episodes from “The Divine Comedy,” although the composer also drew on the works of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. “When writing Dante, it wasn’t my intention to mirror “The Divine Comedy” line by line, but to give my impression of a life and a work: the lives of Dante and Beatrice and “The Divine Comedy” are, for me, one and the same thing.” Although the composer originally envisioned a four-part setting, he only completed the first two movements. A third movement entitled “The Stygian Lake” only survives in a number of sketches. Deeply chromatic writing adds a mysterious touch to a good many passages, and the inclusion of a women’s voice in the second part adds a decidedly atmospheric touch.

Enrique Granados: Dante (Gemma Coma-Alabert, mezzo-soprano; Barcelona Symphony and Catalonia National Orchestra; Pablo González, cond.)

Paradiso, Ceiling by Philipp Veit

In 1865, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) declined the invitation to write a piece of music to celebrate Dante’s birthday. The composer writes, “I was forced to refuse to do a piece for Dante’s centenary. It is the only circumstance for which I would have departed from my habits, but it would have been impossible for me to do anything that could be tolerated.” Yet, Verdi was full of praise and enthusiasm when it came to Dante. “Yes, Dante is really the greatest of all,” he exclaimed. “Homer and Shakespeare are great and often sublime, but neither so universal nor so complete.” In 1880, Verdi crafted a small and expressive setting of the “Ave Maria” for solo soprano and strings. However, the text is not based on the Latin text, but on an Italian version of the Marian prayer. In fact, Verdi took it from a long poem known as the “Credo di Dante,” which contains “texts of faith and prayers, whose author, according to recent research, is probably not Dante.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Verdi: “Ave Maria” (Margaret Price, soprano; Geoffrey Parsons, piano)