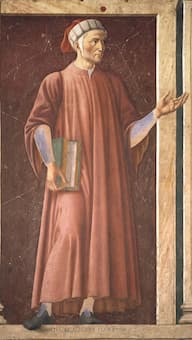

Dante Alighieri, by Giotto di Bordone, c. 1335

The poet, writer and philosopher Dante Alighieri—who died in Ravenna 700 years ago—is widely considered one of the most influential creative minds in Western culture. His “Divine Comedy” is not only one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages, it also is one of the greatest literary works in the Italian language. You see, Dante wrote it in the vernacular Tuscan dialect instead of Latin, and thereby helped to establish the modern-day Italian language. The narrative poem originally called “Commedia” falls into three equal parts, “Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven.” The poem is at once extremely simple and linear, yet extremely complex. “Over a cantus firmus, represented by the realistic narrative of the journey, Dante wove the equivalent of many polyphonic strands by giving the story an allegorical dimension, by introducing prophecies, flashbacks, digressions and learned discourses, and by spinning a complex web of correspondences and patterns of meaning through a virtually unbroken flow of simile, metaphor and allusions to history, myth and legend.” Dante’s descriptive and narrative style provided inspiration for countless works of Western art for more than 650 years.

Franz Liszt: Dante Symphony (Netherlands Philharmonic Chorus; Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra; Hartmut Haenchen, cond.)

Portrait of Dante by

Andrea del Castagno

Dante was born in Florence into a family that supported the Papacy and openly opposed the Holy Roman Emperor. At age 9, he claims to have fallen in love with Beatrice Portinari, but at the age of 12 he was promised in marriage to Gemma di Manetto Donati. And while he wrote several sonnets to Beatrice, his wife Gemma is not mentioned in his writings at all. When Beatrice unexpectedly died in the 1290s, Dante immersed himself into the study of philosophy, logic, ethics, physics, metaphysics and theology. As a leading member of a group of young poets, Dante initiated a transformation of the style and content of the fashionable, elevated love-lyric. In addition, he also began to be active in the political life of the turbulent Florentine Republic. He did rise to political office, but a coup d’état by his political opponents in November 1301 forced him into exile.

Luzzasco Luzzaschi: “Quivi sospiri, pianti e alti guai” (Les Cris de Paris; Geoffroy Jourdain, cond.)

Dante in Verona, by Antonio Cotti

Dante fled to Verona and possibly Lucca, and some sources claim that he even visited Paris and Oxford. He conceived the “Divine Comedy” in exile and completed his masterwork one year before his death in 1321. The narrative describes the state of the soul after death, and the poet travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. “Allegorically the poem represents the soul’s journey towards God, beginning with the recognition and rejection of sin (Inferno), followed by the penitent Christian life (Purgatorio), which is then followed by the soul’s ascent to God (Paradiso).” It is a powerful and imaginative vision of the afterlife representing the medieval view developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. Literary critics suggest that “Dante was the first writer to depict human beings as the products of a specific time, place and circumstance as opposed to mythic archetypes or a collection of vices and virtues; the Divine Comedy could be said to have inaugurated realism and self-portraiture in modern fiction.” Dante also continued to pursue his philosophical studies, and he wrote several prose works while continuing to compose lyric poetry.

Gioachino Rossini: Otello – Act III: Danzone del gondiero: Nessun maggior dolore (Gondoliere, Desdemona, Emilia) (Frederica von Stade, mezzo-soprano; Nucci Condo, mezzo-soprano; Alfonso Leoz, tenor; Philharmonic Orchestra; Jesús López-Cobos, cond.)

Posthumous portrait of Dante in tempera

by Sandro Botticelli, 1495

Dante never returned to Florence and spent his final days in Ravenna. Apparently, he had contracted malaria while returning from a diplomatic mission, and he died on 14 September 1321 at the age of 56. Almost immediately, the city of Florence made repeated requests for the return of his remains to his native city. Ravenna refused but Florence nevertheless built a tomb for Dante in the Basilica of Santa Croce in 1829. And in 2008, the Municipality of Florence officially apologized for expelling Dante 700 years earlier. Dante has been called the “chief imagination of Christendom,” and only one other poet in the modern world, William Shakespeare, shares his preeminence. “Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them. There is no third. In fact, they rival one another in their creation of types that have entered into the world of reference and association of modern thought. Like Shakespeare, Dante created universal types from historical figures, and in so doing he considerably enhanced the treasury of modern myth.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Charles Villiers Stanford: 3 Rhapsodies from Dante, Op. 92 (Benjamin Frith, piano)

In the end Dante ultimately prevails over Shakespeare…he is indeed the ‘Supreme Poet’