Let us continue with our exploration of unfinished classical masterpieces.

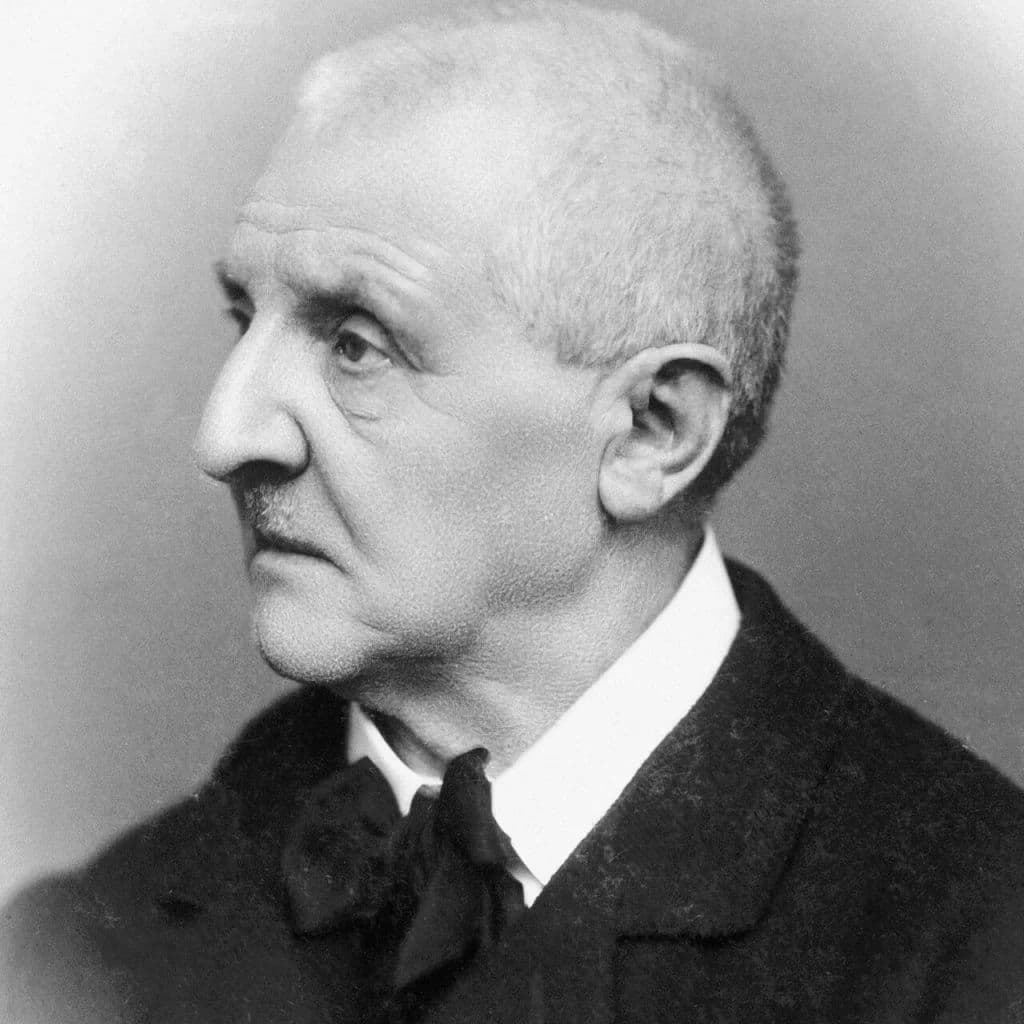

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 7

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 7 (Russian State Cinematographic Orchestra; Sergei Skripka, cond.)

Roughly one year after completing his Fifth Symphony, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was looking to crown his musical career with a grand symphony. Apparently, he fleshed out a preliminary program, “The ultimate essence … of the symphony is Life,” he writes. “First part – all impulse, passion, confidence, thirst for activity. Must be short (the finale death – result of collapse). Second part love: third disappointments; fourth ends dying away (also short).” He worked on the piece over a number of months, and in 1892 the first movement and the finale were fully sketched. The rest of the work was drafted shortly thereafter, and a premiere was scheduled at a charity concert.

In the event, Tchaikovsky had second thoughts and wrote, “It’s composed simply for the sake of composing something; there’s nothing at all interesting or sympathetic in it. I have decided to discard and forget it… Perhaps the subject still has the potential to stir my imagination.” The composer did reuse the first movement in his Third Piano Concerto, and Sergei Taneyev reworked the Andante and Finale for piano and orchestra. The Soviet composer Semyon Bogatyrev returned all music to the symphonic realm, and it first sounded as a symphony in 1957. Some critics have suggested that Tchaikovsky’s 7th sounds like “the composer on mood-stabilizing medication.” That seems a bit harsh to me, but it does bring up the question of whether we should tinker with music the composer considered unworthy.

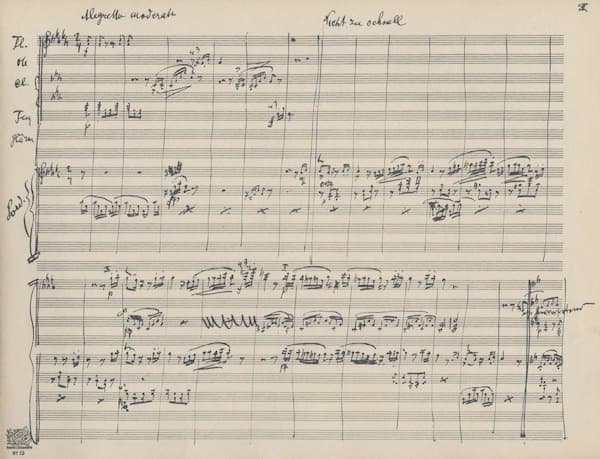

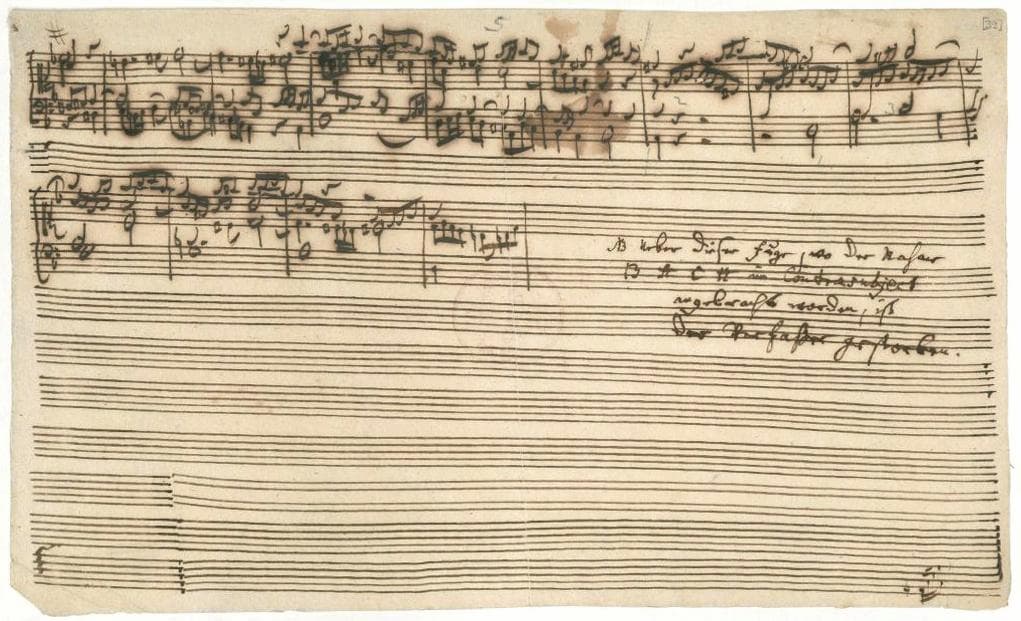

Schubert: Quartettsatz D703

Franz Schubert left us a substantial number of incomplete and unfinished compositions. Commentators have suggested a number of reasons, but the most compelling has to do with Schubert’s financial situation. Unlike his famous contemporary Beethoven, Schubert never really could rely on aristocratic patronage, and he never received official appointments. His music was known throughout Vienna but rarely translated into a suitable income. As such, he quickly jumped at possible opportunities to earn a proper wage, and he discontinued all ongoing composition projects at the drop of a pin. Such might have been the case with the “Quartettsatz” in C minor, D 703. Schubert completed the first movement of the intended string quartet No. 12 and drafted 41 additional bars for the exposition of the andante movement. In his mind, the work surely was fully formed. However, external circumstances caused Schubert to abandon the composition.

© tonebase.co

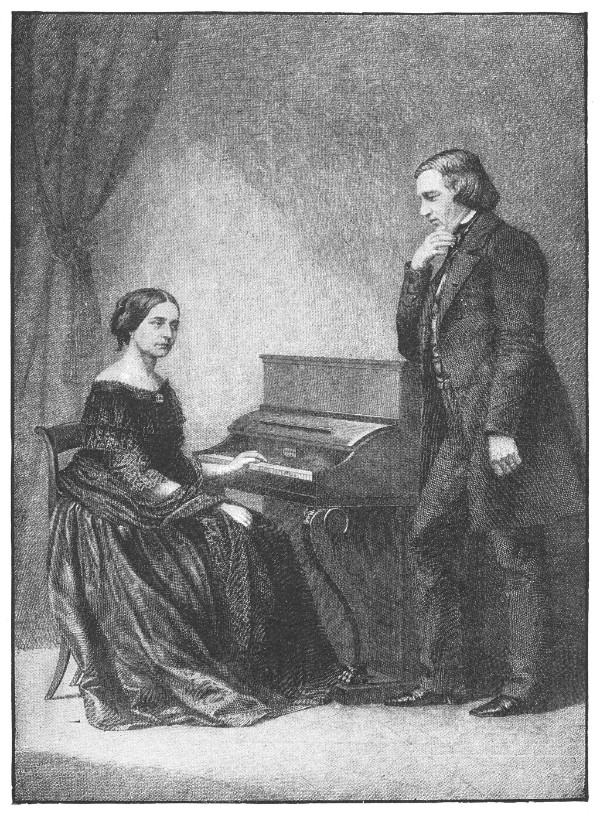

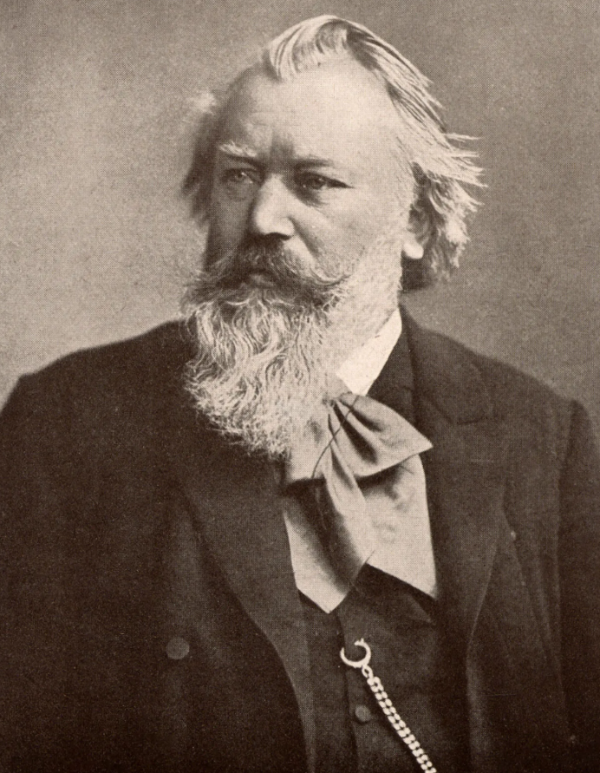

Johannes Brahms subsequently owned the manuscript of the “Quartettsatz,” and after some editing, brought the score to publication. It first sounded on 1 March 1867 in Vienna. Brahms did not touch the incomplete andante movement; it was twice restored in recent times.

Jacques Offenbach: Les contes d’Hoffmann, “Barcarolle”

Jacques Offenbach, because he was born and raised in Germany, was increasingly and predictably unpopular in France following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Yet his popularity in England and Vienna was undiminished, and he even embarked on a highly successful tour of the United States. He gave a series of more than 40 concerts in New York and Philadelphia, and once he had returned to Europe, he was feverishly working on completing the score of his fantastic opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Offenbach was seriously ill, and he supposedly told his dog, “I would give everything I have to be at the premiere.” In the event, Offenbach did not live to finish the work, and he died four months before its premiere. Offenbach had completed the piano score and orchestrated the prologue and the first act. Different editions quickly emerged, and the version premiered was fashioned by Ernest Guiraud. Over time, new editions were released, and the emphasis on authenticity produced various versions that had to be edited and re-edited as more authentic music was found. The variables proposed are enough to make your head spin, but the “Barcarolle” will remain an all-time favourite.

Gustav Mahler: Piano Quartet in A Minor

Gustav Mahler as a child

Gustav Mahler was the son of a tavern proprietor and a soap-maker’s daughter. He certainly was a musical wunderkind, as he discovered his grandparent’s piano at the age of four. He gave his first public performance at the age of 10, and to further his musical education, he enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory. He took piano lessons from Julius Epstein, and studied composition and harmony under Robert Fuchs and Franz Krenn. He received his diploma in 1878 but was not given the coveted and prestigious silver medal for outstanding achievement. Mahler claimed to have written hundreds of songs, several theatrical works and various chamber music compositions, but the only surviving document is a single movement for a Piano Quartet in A minor. It did receive the conservatory Prize in 1876, and the movement was strongly influenced by the musical styles of Schumann and Brahms. Mahler was only 16 years old, and we really don’t know if he ever drafted additional movements for this work. There seems to be a consensus that he did not.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter