In his 2009 violin concerto, composer Brett Dean looked at an art form that is not only being lost in today’s world but being replaced with something that gives a different level of satisfaction: the letter.

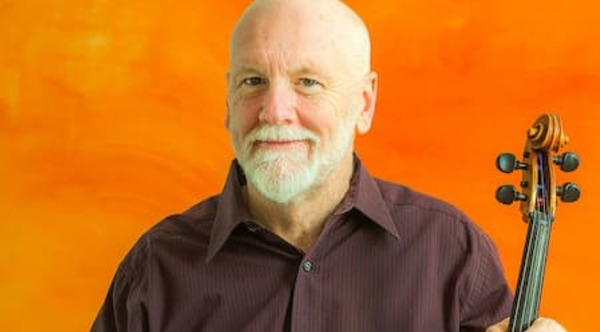

Brett Dean

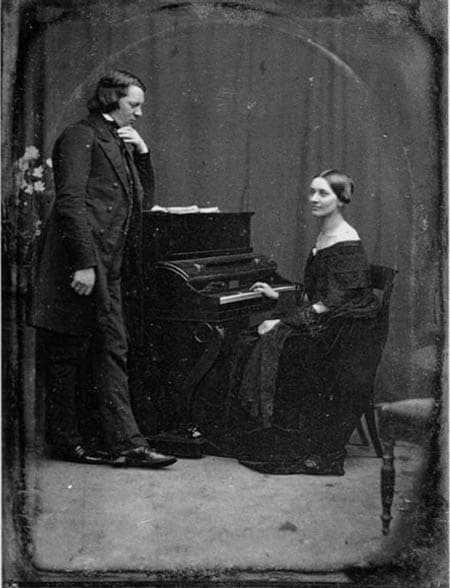

The Lost Art of Letter Writing looks at 4 letters written in the 19th century. The earliest is from Johannes Brahms to Clara Schumann, dated 15 December 1854. Robert Schumann had been committed to a mental sanitorium from February 1854, and was to die there in July 1856. Johannes Brahms has been supporting the Schumann family since Robert’s hospitalization.

Clara and Robert Schumann

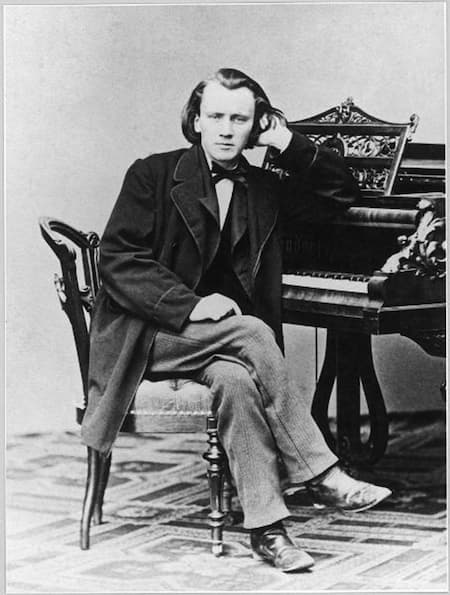

In July 1854, Brahms dedicated to Clara his Variations on a Theme of Schumann, Op. 9. His letter of 15th December reads, in part: ‘Would to God that I were allowed this day instead of writing this letter to you to repeat to you with my own lips that I am dying of love for you. Tears prevent me from saying more.’ He’s making reference to a story from the 1000 and One Nights, where a son who will not marry is imprisoned only to wake one day to find the most beautiful woman next to him, and when he wakes next, she is gone. The only evidence of the invisible woman is the ring he took from her finger. After many travails, they find each other again and marry. The whole story is extremely full of sexual desire and in making his light reference, Brahms is making a euphemism of a deeply felt desire.

Johannes Brahms

After the death of Robert, Brahms proposed to Clara but, probably for everyone’s benefit, she turned him down; they remained friends until her death in 1896.

Brett’s movement is full of that longing in Brahms’ letter. Clara is still married to the institutionalized Robert, and Brahms desires for so much more than friendship.

Brett Dean: The Lost Art of Letter Writing – I. Hamburg, 1854 (Frank Peter Zimmermann, violin; Sydney Symphony Orchestra; Jonathan Nott, cond.)

Brett’s second letter is one from Vincent van Gogh to his fellow painter and mentor Anthon van Rappard, dated 19 December 1882, writing about how the eternal beauty of nature is the constant in his unstable life: ‘My intercourse with artists has stopped almost completely, without my being able to explain precisely how and why this has come about. All kinds of eccentric and bad things are thought and said about me, which makes me feel somewhat forlorn now and then, but on the other hand it concentrates my attention on the things that never change – that is to say, the eternal beauty of nature.’

Van Gogh: Part of a Portrait of Anthon van Rappard, 1884

(Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation))

John Peter Russell: Portrait of Vincent van Gogh, 1886

(Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation))

He goes on in the letter to compare himself with Robinson Crusoe, who, he says ‘created an active life for himself because he was so lonely…’. The movement is described by the composer as ‘prayer-like’ and has a contemplative feel.

Brett Dean: The Lost Art of Letter Writing – II. The Hague, 1882 (Frank Peter Zimmermann, violin; Sydney Symphony Orchestra; Jonathan Nott, cond.)

The third letter comes from Vienna in 1886. The composer Hugo Wolf writes to his brother-in-law Josef Strasser to decline his nomination as godfather to Josef’s child: ‘It grieves me, but I know now for certain: that it is my lot to hurt all those who love me, and whom I love.’

The entire letter is a confession of Wolf’s inability to resolve the difference between his loving and good-hearted side and the dark, angry one that drove him to say no. Wolf was known to be extremely temperamental and this letter shows his own awareness of it and his inability to fight against it. His biographer, Ernest Decsey, declared it to be Wolf’s own Hieligenstadt Testament, comparing it to Beethoven’s near-suicide letter after dealing with the realities of his increasing deafness.

Hugo Wolf

Brett Dean: The Lost Art of Letter Writing – III. Vienna, 1886 (Frank Peter Zimmermann, violin; Sydney Symphony Orchestra; Jonathan Nott, cond.)

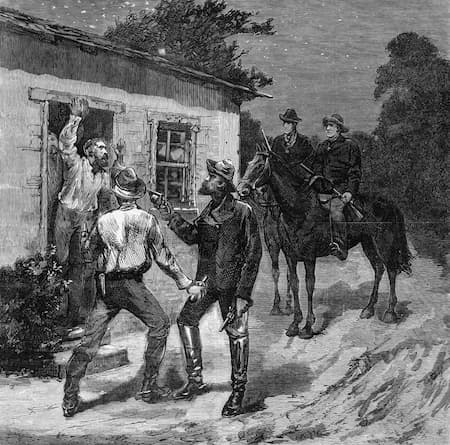

The final movement removes us completely from the 19th-century world of composers and artists and takes us to Jerilderie, Australia, located at the southern border of New South Wales. This small town was visited by the outlaw Ned Kelley and his gang in 1879. The gang turned the tables on the local police by not only capturing them and imprisoning them in their own cell but also taking their uniforms and pretending to be policemen sent from Sydney (660 km / 400 m. to the northwest) to protect them against the Kelly Gang. While in Jerilderie later, holding up the bank, Kelly dictated to his friend Joe Byrne what has become known as the Jerilderie Letter, where he states his innocence against a number of accusations including horse theft, declares his brother’s innocence against a charge of assaulting a woman, describes how the local constable stole his horses and others of the neighborhood, etc. It’s an extraordinary 56-page document that rambles and accuses and excuses and then closes asking for leniency and justice: ‘‘It will pay Government to give those people who are suffering innocence justice and liberty, if not I will be compelled to show some colonial stratagem which will open the eyes of not only the Victorian Police and inhabitants but also the whole British army and no doubt they will acknowledge their hounds were barking at the wrong stump… I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning but I am a widow’s son, outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.’

The Kelly Gang holds up the Jerilderie Police Station

Brett Dean: The Lost Art of Letter Writing – IV. Jerilderie, 1879 (Frank Peter Zimmermann, violin; Sydney Symphony Orchestra; Jonathan Nott, cond.)

Dean has used letters from the 19th century that are full of more than just the words on the page: Brahms’ frustrated desire, Van Gogh’s recognition of his self-made loneliness, Wolf’s statement of the two characters he argues with, and Kelly’s attempt to right history. Each letter contains something that the audience can understand and recognize in themselves or their life and, in setting it to music, Dean reaches across history to make a connection with today’s world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter