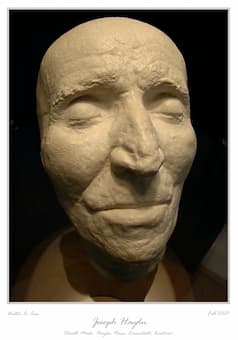

Haydn’s death mask

The story of Haydn’s funeral and last remains is complicated and pretty macabre. It all starts in 1771, when Haydn was director of the Esterházy court orchestra. He conducted and wrote music for that ensemble for many, many years, and he composed his E-minor Symphony in that year. Many of his minor-key symphonies are associated with the literary movement known as “Storm and Stress,” and they feature increased dissonance, chromaticism and driving rhythms. Above all, they tend to be highly emotional and moving compositions. The E-minor Symphony No. 44 carries the nickname “Mourning,” because Haydn supposedly asked that the slow movement should to be played at his own funeral. We really have no idea if that story is true or not, but we do know that it was in fact not performed at his funeral or any of the memorial services that followed.

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 44 in E minor, (Mourning) – III. Adagio (Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra; Ádám Fischer, cond.)

Haydn’s House (Haydnhaus), Vienna

Fast-forward 40 years, and on 26 December 1803 Haydn performed his last public musical function conducting the “Seven Last Words.” Haydn rarely left his home in Gumpendorf—then a suburb of Vienna—and he was last seen publically on 27 March 1808. On the occasion of his 76th birthday, Antonio Salieri conducted a gala performance of “The Creation” in the Great Hall of the University with the composer in attendance.

Haydn progressively weakened, and he signed his last will on 7 February 1809. Haydn did witness the bombardment of Vienna by French troops in May of that year. His neighborhood came under attack, and a biographer reported, “Four shots fell, rattling the windows and doors of his house.” Supposedly, Haydn loudly proclaimed, “don’t be afraid, children, where Haydn is, no harm can reach you.” The Habsburg Emperor and his entourage had long fled the city, but such was Haydn’s fame across Europe that Napoleon ordered a guard of honour to be stationed at Haydn’s house. It is reported that his last known visitor was a French officer named Sulémy, who paid his respects by singing an aria from “The Creation.” According to the Haydn’s copyist Joseph Elssler, the composer played the “Emperor’s Hymn” on 26 May “with such expression and taste that our good Papa Haydn was astonished about it himself, and he was very pleased.”

Joseph Haydn: String Quartet No. 62, Op. 76, No. 3 “Emperor” – II. Poco adagio, cantabile (Alban Berg Quartet)

Haydngasse

Following this impromptu performance, Haydn had to be assisted to bed, and he did not rise again. It is reported that he peacefully died in his home at 12:40 am on 31 May 1809. The Haydn house and garden was then located at “Kleine Steingasse,” and it was completely remodeled and re-designed by the composer who had bought it in 1797. Currently, the street address has changed to Haydngasse 19, but the house and garden are still there. In fact, it is now a museum with permanent exhibitions dedicated to Haydn and to Brahms.

Michael Haydn

Back in 1809, Haydn’s initial funeral the following afternoon was a simple affair, hardly surprising during a time of war. Haydn was laid to rest at the Hundsturm Cementery, one of five new cemeteries established by Emperor Joseph II who decided that all of Vienna cemeteries should be located outside the city walls. Today, this location is a public park, unsurprisingly named after the composer. Some sources indicated that on 2 June 1809 the “Requiem” by Joseph Haydn’s brother Michael Haydn (1737-1806) was performed in his honor at the Gumpendorf Church.

Michael Haydn: Requiem in C minor, MH 559 (Cantemus; German Chamber Academy Neuss; Werner Ehrhardt, cond.)

Schottenkirche (Scots Church) in Vienna, 1758

A great memorial service was held two weeks later, on 15 June 1809, at the Schottenkirche (Scots Church) in Vienna. According to contemporary newspaper reports, “the whole of Viennese society appeared and many French officers, artist and other French admirers of Haydn attended the service, including the French writer Stendhal.” And on that solemn occasion, the “Requiem” by Haydn’s late friend Mozart was performed.

Schottenkirche (Scots Church) in Vienna

Sadly, however, that’s not the end of this story. In the evening of 17 June 1809, Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a former secretary of Haydn’s employer Prince Esterházy and the phrenologist Johann Nepomuk Peter returned to the graveyard and exhumed Haydn’s body. They hacked off the composer’s head and the ensuing phrenological examination revealed that Haydn’s skull displayed a fully formed “bump of music.” Having thus contributed to “science,” Haydn’s head was stripped of flesh and muscle, and his brain removed. The cleaned skull was placed in a wooden box and became part of Peters’ personal collection.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Requiem in D minor, K. 626 (Wilma Lipp, soprano; Elizabeth Hoengen, alto; Murray Dickie, tenor; Ludwig Weber, bass; Singverein Wiener, choir; Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Jascha Horenstein, cond.)

Haydnkirche in Eisenstadt

We might never have known about these morbid doings if Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II had not insisted of giving Joseph Haydn a proper funeral in 1820. But when they made plans to have Haydn’s remains transferred to the family seat in Eisenstadt, it was discovered that the head was missing. The Prince was outraged, and the guilty parties quickly identified.

Haydn’s crypt of the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt

Yet Peter and Rosenbaum had no intention of giving up the real skull, but purchased a substitute skull from a mortician. Thus, the fake head together with Haydn’s body was transferred to the crypt of the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt. To cut this macabre story short, it took 145 years before Haydn’s head was reunited with his body. And just in case you are wondering, the substitute skull was never removed—to this day Haydn’s tomb contains two skulls.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Joseph Haydn: The Creation (Margaret Marshall, soprano; Vinson Cole, tenor; Gwynne Howell, bass; Lucia Popp, soprano; Bernd Weikl, baritone; Hedwig Bilgram, harpsichord; Bavarian Radio Chorus, choir; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Rafael Kubelík, cond.)