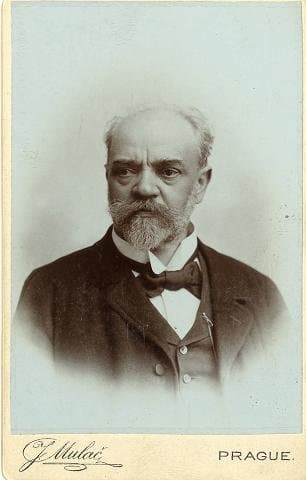

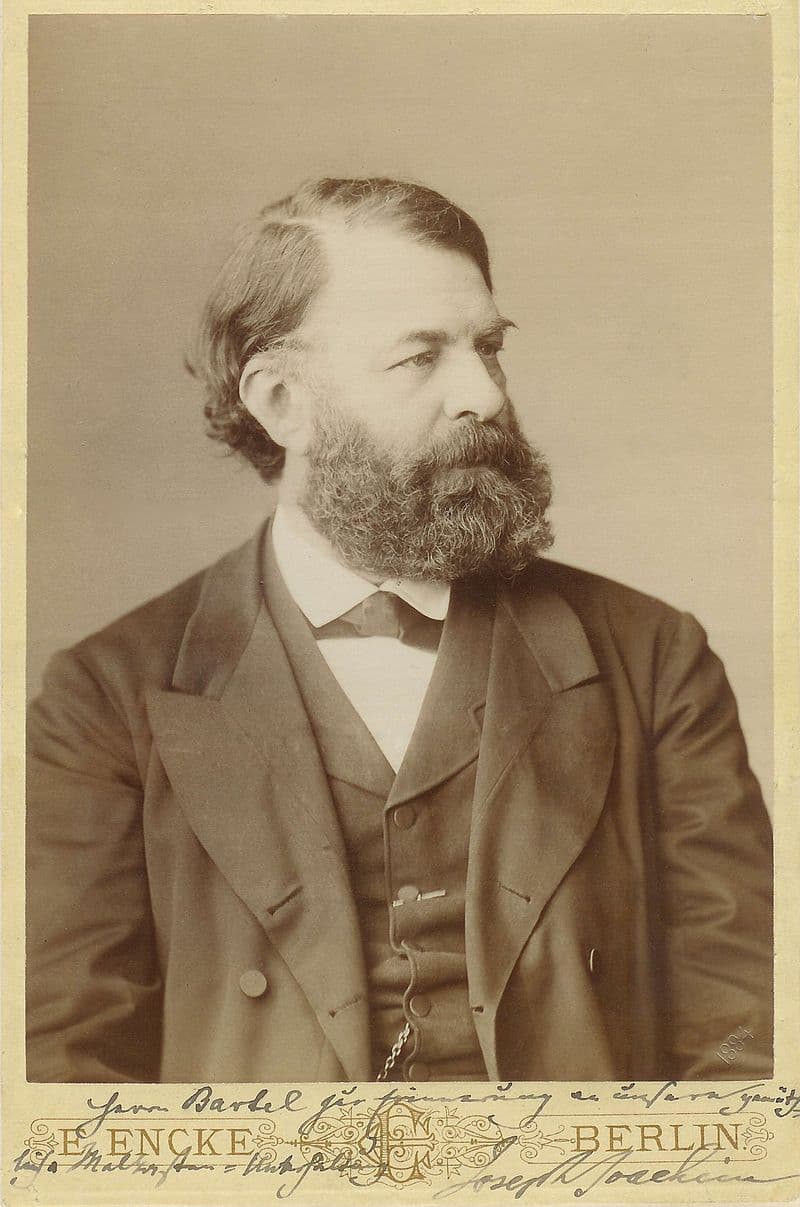

The fierce music critic Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904) became aware of Antonín Dvořák’s music when he was a member of the commission which offered state scholarships to impoverished young musicians. In fact, Hanslick was instrumental in furthering Dvořák’s career by taking a lively interest in all the composer’s new works.

Antonín Dvořák in Spillville

Hanslick extensively promoted Dvořák in German-speaking countries, primarily to attack proponents of program music. “I cannot think of setting Dvořák,” he writes, “on the same level as Richard Strauss. Dvořák is a genuine musician, who has proved a hundred times that he requires no program and no epigraph in order to delight us with pure, independent music. He arouses in us thoughts and feelings, showers of joy and sadness, without the need of the swindle of false erudition.”

Eduard Hanslick

On one occasion, Hanslick travelled to Prague to attend the premiere of the opera Dimitrij, and the composer, aware of Hanslick’s international influence and renown, radically revised the work on the basis of his critical remarks. When Dvořák turned his attention towards program music in his symphonic poems, Hanslick was not amused.

Eduard Hanslick and Richard Wagner

He writes, “I am an appreciative audience where Dvořák’s music is concerned, perhaps I perceive its appeal all too keenly yet, even so, I could not remain silent regarding the dangers of this latest tendency. Dvořák has no cause to go begging before literary texts, that might bolster his composition. His rich musical invention needs no loans, crutches, or instruction. It is with a strange passion that Dvořák now indulges in ugly, unnatural, and ghastly stories which correspond so little to his amiable character and to the true musician that he is.”

Antonín Dvořák: The Water Goblin, Op. 107 (Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Hans Zimmer, cond.)

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Karoline Bjørnson together with Nina and Edvard Grieg

The Norwegian composer and pianist Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) first met Dvořák during his visit to Vienna in 1895. Grieg “spent much time with Brahms, who was friendly and in high spirits.” Grieg added, “I could not say the same of Dvořák.” Grieg got to know him much better in 1903 when he came to Prague to conduct his own works. That concert included a selection of his songs performed by Dvořák’s daughter Magda. Grieg reports, “There was a young singer, the composer’s daughter. She sang with warmth, but in Czech, which made the situation somewhat more difficult for me.” Dvořák attended the concert and visited Grieg in his dressing room. Grieg in turn attended a performance of Rusalka at the National Theatre and went to see the Dvořák family at home. Grieg writes, “My time spent with Dvořák was very pleasant. If I might put it delicately, he has his own temperament, but he was very kind.” After Dvořák’s death in 1904, Grieg published an obituary article in a Norwegian magazine, in which he spoke very highly of Dvořák and his music.

Antonín Dvořák: Rusalka, Op. 114 (Sarah Crane, soprano; Taryn Fiebig, soprano; Dominica Matthews, mezzo-soprano; Bruce Martin, bass; Cheryl Barker, soprano; Anne-Marie Owens, mezzo-soprano; Rosario La Spina, tenor; Barry Ryan, baritone; Sian Pendry, soprano; Elizabeth Whitehouse, soprano; Opera Australia Chorus; Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

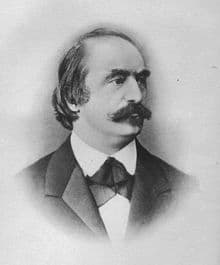

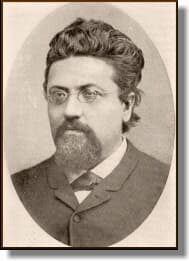

Joseph Joachim

In 1879, Dvořák’s publisher Simrock commissioned the composer to write a violin concerto. Dvořák was given free reign in artistic matters, but the publisher specified that the famed violinist, composer, and conductor Josef Joachim (1831-1907) was to play the world premiere. Dvořák and Joachim had previously met, and the violinist was a great admirer of Dvořák’s music. Dvořák composed the original version with Joachim recommending certain changes. He worked these changes into the score and presented the concert to Joachim with the following dedication, “I dedicate this work to the great Maestro Jos. Joachim, with the deepest respect.” Several revisions later, Dvořák received a detailed letter from Joachim in August 1882, in which the violinist proposed further changes. Dvořák agreed, and traveled to Berlin in September to play the work with Joachim.

Seemingly, everything went well as he wrote to Simrock, “I played the violin concerto with Joachim twice. He liked it very much… I was very glad that the matter has finally been sorted out. The issue of revision lay at Joachim’s door for a full two years!! He very kindly revised the violin part himself; I just have to change something in the Finale and refine the instrumentation in a number of places.” However, once Dvořák had finished the final revisions to the score in December 1882—almost four years after the initial commission—Joachim had lost interest. In fact, Joachim probably never played the work, and he certainly was not involved in the premier performance on 14 October 1883.

Antonín Dvořák: Violin Concerto, Op. 53 (Midori Goto, violin; New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Zubin Mehta, cond.)

Alois Gobl

Alois Gobl (1841-1907) was the personal secretary to Prince Kamil Rohan, and administrator at Sychrov Castle. During his visits to Prague—Gobl was an excellent amateur musician and baritone—he became acquainted with Dvořák. They developed a close friendship and Dvořák visited Sychrov Castle nine times between 1877 and 1896. Gobl was godfather to most of Dvořák’s children, and his youngest daughter was named “Aloisie” in honor of his friend. During his time at Sychrov, Dvořák worked on a number of compositions, and several of Dvořák’s short sacred works received their premieres in Sychrov chapel. Gobl and Dvořák exchanged copious amounts of letters, and on 10 August 1889 Dvořák wrote to his friend. “You want to know what I’m doing? I have my head full; if only humans could write that down right away! But what use is it, I have to go slowly as far as the hand will and God will give the rest … It’s easy beyond expectation and the melodies just fly to me…” At the time of this letter, Dvořák was completing his piano quartet Op. 87, and within weeks he had finished the first drafts for a new symphony. Those beautiful melodies that flew into his head found a home in Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony, completed in the autumn of 1889.

Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 8 in G major, Op. 88 (Baltimore Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

Marie Červinková-Riegrová

The Czech author, librettist, and translator Marie Červinková-Riegrová (1854-1895) was the daughter of the leading Czech politician František Ladislav Rieger, and a granddaughter of the famous historian František Palacký. She spoke several languages and applied herself to literary, artistic, and charitable pursuits. In fact, she first translated the libretto of Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin into Czech. And she accompanied Dvořák and Tchaikovsky during their meetings in Prague in the spring and autumn of 1888. Her first libretto was originally written for her husband Václav Červinka, but it was set ultimately by Šebor. Dimitrij was also written expressly for Šebor, but unable to handle the demands, the libretto went to Dvořák. Dvořák and Červinková-Riegrová worked closely together, and she complied conscientiously with Dvořák’s many requests for modifications. Dvořák produced several versions, and while this grand opera has fallen into neglect, Červinková-Riegrová’s libretto has been widely praised, especially in comparison with that of Dvořák’s previous opera, Vanda. Most compelling is the impossible love between Dimitrij and Xenia. Xenia has been traumatized by the events following the death of her father (Ivan the Terrible), and Dimitrij, unaware that he is in fact an impostor and the son of a serf, suffers from a lack of identity at an existential level. Outwardly brave and forceful as a leader, he is needy and weak in intimate relations, at least with Xenia.

Antonín Dvořák: Dimitrij, Op. 64 (Leo Marian Vodička, tenor; Drahomíra Drobková, contralto; Magdaléna Hajóssyová, soprano; Livia Aghova, soprano; Peter Mikuláš, bass; Ivan Kusnjer, baritone; Ludek Vele, bass; Zdeněk Harvánek, vocals; Paul Haderer, bass; Prague Philharmonic Chorus; Prague Radio Choir; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra; Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

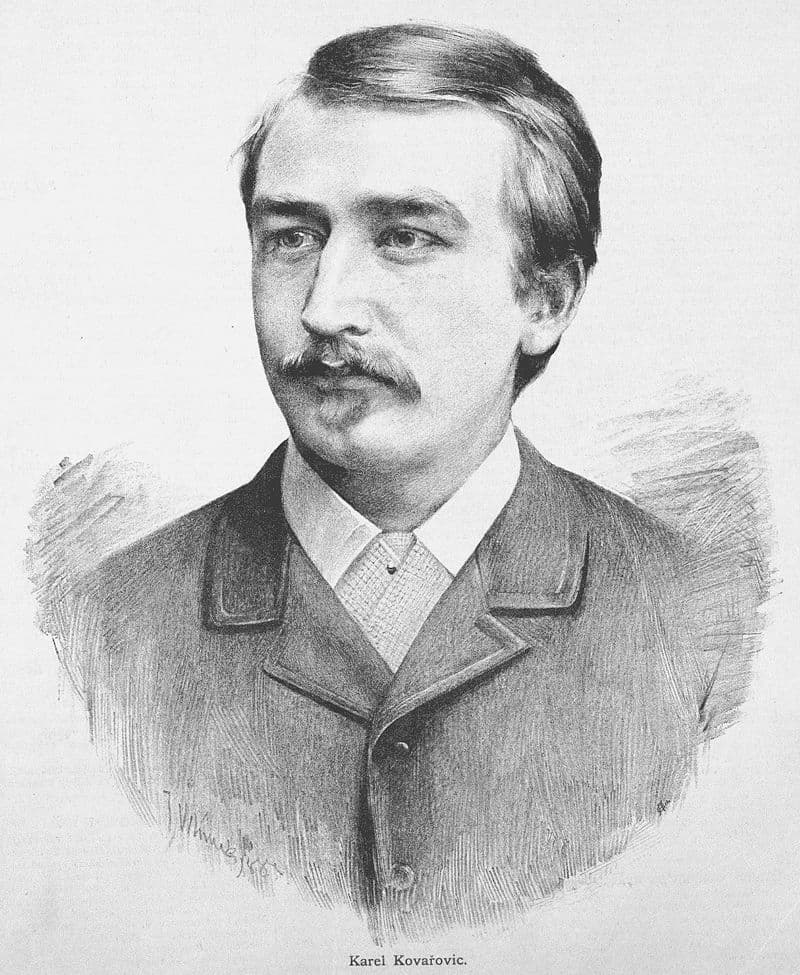

Karel Kovařovic

The Czech conductor and composer Karel Kovařovic (1862-1920) was head of the National Theatre Opera in Prague between 1900 and his death. As such, he is widely considered the most important Czech opera conductor of his time. He primarily focused on works by Czech composers, whose scores he mercilessly revised. For one, he presented the premiere of Dvořák’s Rusalka and a stage production of his oratorio Saint Ludmila. Kovařovic was also rather interested in the opera Dimitrij, whose individual versions he subjected to a comparative study, which eventually gave rise to the “Kovařovic” version, now used for the majority of productions to date. It has been suggested that the failure of the premiere of Dvořák’s last opera Armida was caused by Kovařovic’s withdrawal from his commitment to rehearse the work for apparent health reasons. Kovařovic is mostly remembered today for the revisions he made to Leoš Janáček‘s Jenůfa, and it was in his version that the opera was heard for many years. It has even been suggested that his revisions arguably improved the work. Be that as it may, Kovařovic was an outstanding pianist and he took part in the premiere of Dvořák’s Piano Quintet in A major, Op. 81.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 81