Sergei Prokofiev in 1918

Then, who was Anatoly Lunacharsky, and why would he help Sergei Prokofiev?

Unlike many Soviet politicians, Anatoly Lunacharsky was the disciple of Lenin rather than his slave. He had become interested in Marxism at age 15, while studying at the gymnasium in Kiev. Subsequently, in 1895, Lunacharsky entered the University of Zurich to study philosophy and natural science. He devoted his energy to analysing works by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and was greatly influenced by the idealistic views of the lecturer Richard Avenarius, an advocator of subjective idealist philosophy. He left the University without a degree, joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), an early Marxist political group. When he returned to Russia in 1896, he was sent to Siberia for his party activities, returning to Kiev in 1901.

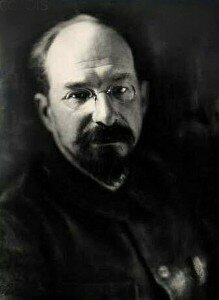

Anatoly Lunacharsky

Prokofiev: The Steel Step, Op. 41bis: I. Entry of the People (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Although Anatoly Lunacharsky headed “Vperyod,” a left-wing group in opposition to Lenin, he still returned to Russia after the February Revolution of 1917. With the downfall of the Russian Empire and the declaration of the republic, he re-joined the Bolsheviks and was appointed Commissar of The People’s Commissariat for Education (Narkompros) in October 1917, which is equivalent to the Minister of Education and the Arts. Lunacharsky remained in this position until 1929.

Narkompros gathered together the most talented and prestigious intellectual elites in the Bolshevik ranks. The department was responsible not only for education but also for all sectors of science, art, and culture, since the Soviet People’s Committee in Russia at that time did not have an independent commissioner for those disciplines.

Lunacharsky reserved special affection for music. When he took office, there was a movement to discard music of former times. Tchaikovsky was called a ‘feudal lord’, and Chopin was a ‘bourgeois aesthetician.’ The works of the past were viewed with suspicion and even Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov’s music, which were deeply rooted in Russia, were strongly criticized. It was even suggested that their music be banned.

Lunacharsky defended music, saying: We don’t have ready-made Revolutionary repertoire, and we cannot offer other works; it needs time to replenish. Lunacharsky was also less hostile to music from Europe (otherwise viewed as bourgeois and therefore bad), and highlighted the cultural significance of classical music. In the case of Richard Strauss, for example, Lunacharsky thought his work was full of Individual heroism, but it was important in giving courage to the proletariats to fight and win. He also held strong views on modern music. He called Scriabin’s music “the greatest gift of musical romanticism of the revolution,” and yet thought that all composers after Beethoven were too preoccupied with expressing personal feelings. Since Beethoven’s music speaks to all human beings, this made Beethoven a pioneer in socialist art. Lunacharsky’s works can be accessed here. Both Lunacharsky and Lenin agreed that the cultural organizations should be nationalized. Narkompros set up a musical division, MUZO; ran musical institutions, replacing Glazunov’s Imperial Russian Musical Society in July 1918; and required that all programmes, posters, and even tickets get approval before publishing. It was even worse than it had been under the Tsar.

These policies led to the flight of intellectuals to other countries. However, Lunacharsky did not hold a tough proletarian stance. The People’s Commissariat for Education became the first and only gateway to go abroad, and Lunacharsky became the man in control of this access point, as few members of the People’s Commissariat dared to accept intellectuals’ applications for going abroad, let alone giving approval.

Lunacharsky seemed not to worry about the talent drain. Prokofiev was just one of many artists including Chaliapin, Gretchaninov, and others, who were free to travel.

Glinka: Nochnoy smotr (The Night Review) (Feodor Chaliapin, bass)

Lunacharsky also prevented the great composer Glazunov from being dispossessed of his house. There are obviously exceptions to this liberality. Gregor Piatigorsky, the famous cellist, longed to travel abroad to further his studies. He repeatedly went to Lunacharsky, with whom he was on good terms, to ask permission to leave; but he was always turned down. He was told he was needed in Moscow. Nonetheless, Piatigorsky warned Lunacharsky he would run away if not allowed to leave. Finally, Piatigorsky defected.

Busoni: Kleine Suite (Little Suite), Op. 23: IV. Sostenuto ed espressivo (Gregor Piatigorsky, cello; Lukas Foss, piano)

In dealing with other types of music, Lunacharsky was ruthless. He took jazz song and dance to be a symbol of corruption and pornography, a tool controlled by the capitalist who attempted to disintegrate the Soviet Union from inside, and banned it. Saxophones, whose passion was expressed through its sexy timbre, could not be produced or imported. It was hard to find this instrument in the Soviet Union for many years. But that then is another story.

As Stalin consolidated his power, there was a readjustment of the Party’s policies towards literature and art, and Lunacharsky was out of his post by 1929. Not every artist was able to come and go like Sergei Prokofiev; increasingly Stalin would not allow artists or dissident intellectuals to leave the USSR. He made them disappear quietly in the night. It is no wonder that the climactic gesture of Russian Art was actually before the October Revolution.