In times of crisis, we are always looking for heroes; while losing his left hand in the battle of Lepanto and being held for ransom in prison in Algiers, the author Miguel de Cervantes found his hero in the 16th-century Spanish noble who left home to right the ills of the world.

Don Quixote

Don Quixote de la Mancha is a middle-aged gentleman passionate about reading. In fact, he turns into a bumbling knight who is unable to separate reality from fiction, and he imitates his admired literary heroes to find new meaning in his life. He takes up his lance and sword to defend the helpless and destroy the wicked, and in the process, aids damsels in distress and battles giants, mostly in his own head. The adventures of Don Quixote and his supporting characters have inspired a flood of musical interpretations, among them the magnificent and well-known tone poem by Richard Strauss.

Richard Strauss: Don Quixote, Op. 35 (Theo Olof, violin; Klaas Boon, viola/violin; Tibor de Machula, cello; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Bernard Haitink, cond.)

Kara Karayev

Kara Karayev (1918-1982) was an Azerbaijani composer who studied with Dmitri Shostakovich at the Moscow Conservatory. Upon his return to Baku, he wrote in a variety of genres, including music for plays and musicals, opera, ballet, symphonic and chamber works, romances, cantatas, children’s music, and film music. In his tone poem Don Quixote, Karayev avoided musical illustration, and we find no depictions of the hero’s battles or faithful representations of events. Instead, the composer focuses on the inner world of the protagonist. The opening section, “Travels”, introduces us to the main character, and in the second, we meet his sidekick, Sancho Panza. Don Quixote’s “Death” is the longest section of the work, and when the light is extinguished, we are not left in complete darkness; memories of the likeable hero still remain.

Kara Karayev: Don Quixote (Russian Philharmonic Orchestra; Dmitry Yablonsky, cond.)

Joaquín Rodrigo

Many of Don Quixote’s great deeds of chivalry are performed in the name of an unwitting peasant girl called Dulcinea of Toboso. Joaquín Rodrigo’s (1901-1999) symphonic poem Ausencias de Dulcinea (Dulcinea’s Absence) dates from 1947 and won the first prize at a competition to mark the 400th centenary of Cervantes’ birth. Rodrigo wrote: “Is there anything like dreaming about work? … I delayed for a month and a half. Cervantes alternates grandeur and irony, and the opening fanfares represent the age of chivalry, while oboes, cellos and harps represent the lyricism of unrequited love.” Dulcinea is portrayed by four homogeneous soprano voices, sounding a stark contrast with the full bass voice of Don Quixote as he mourns his bitter solitude. The composer writes, “I saw that by setting four voices around that of Don Quixote, I could establish contrasts between the chivalrous, the ideal and the burlesque. While Don Quixote is deadly serious throughout, the orchestra provides comic touches… The four sopranos reflect the fact that despite searching in the North, South, East or West, Don Quixote will never find his ghost-like Dulcinea.”

Joaquín Rodrigo: Dulcinea’s Absence (José Antonio López, bass; Lilian Moriani, soprano; Victoria Marchante, soprano; Celia Alcedo, soprano; Maria José Suarez, mezzo-soprano; Madrid Community Orchestra; Jose Ramon Encinar, cond.)

Georg Philipp Telemann

We know that Georg Philipp Telemann was a rival and friend of Johann Sebastian Bach. In fact, the Leipzig authorities had originally selected Telemann over Bach for the position of Cantor at St. Thomas. It is probably less well known that Telemann composed a light-hearted suite described as “Burlesque de Quixote.” Telemann follows the conventional narrative with Don Quixote assuming knighthood at the hands of an innkeeper and a concerned priest and barber cementing in the room where Don Quixote keeps his books. Before long, he has recruited Sancho Panza, and together, they famously attack a number of windmills. With his lance shattered, his musical sighs of love for his imagined mistress, Dulcinea, reverberate through the score. His horse Rosinante makes an appearance, as does Sancho Panza’s donkey. The Suite ends with Don Quixote back home and falling sound asleep.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Don Quixote Suite (Northern Chamber Orchestra; Nicholas Ward, cond.)

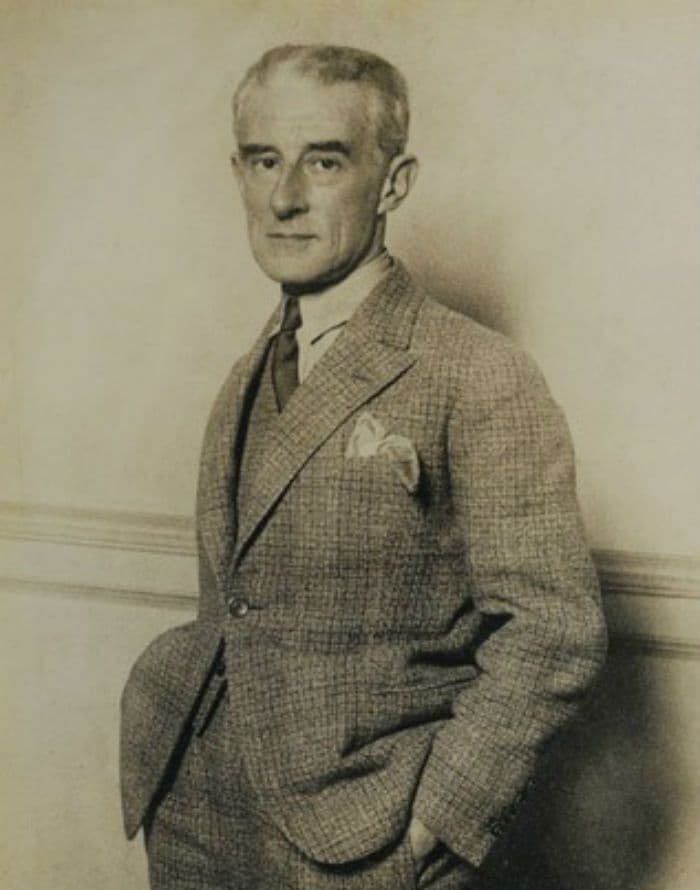

Maurice Ravel

In 1932, Maurice Ravel was part of a competition to provide music for W. Pabst’s film Don Quixote, starring the Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin. Originally, Ravel was asked to compose four pieces but failing health complicated by a car accident severely slowed his progress. Eventually, Pabst fired Ravel and gave the job to Jacques Ibert. In the event, Ravel still managed to complete 3 songs, which turned out to be his final works before his death in 1937. The three songs of Don Quichotte à Dulcinée, poems by novelist Paul Morand, reflect the tenderly sincere and humorous moments of this well-known tale. “Chanson Romanesque” is a sweet ballad in which Don Quixote proclaims his dedication to Princess Dulcinea. “Chanson Epique” is a humble prayer asking for blessings and protection for both him and Dulcinea. The song cycle closes with “Chanson á boire,” a jovial drinking waltz in triple time.

Maurice Ravel: Don Quichotte à Dulcinée (version for voice and orchestra) (Stephen Roberts, baritone; Ulster Orchestra; Yan Pascal Tortelier, cond.)

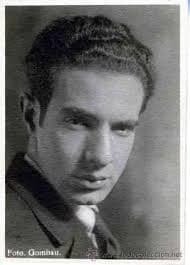

Gerardo Gombau Guerra

Gerardo Gombau Guerra (1906-1971) composed his symphonic poem Don Quijote velando las armas (Don Quixote keeping vigil over his armor) for entry in a composition contest at the Madrid Conservatory in 1945. It was the composer’s first large-scale orchestral work based on chapter III of the novel, “an account of the pleasant method taken by Don Quixote to be dubbed a knight.” Gombau was unanimously awarded first prize as he set out to portray specific episodes from the novel, which are indicated in the score. We hear two distinct themes representing Don Quixote and Dulcinea, respectively. After a tumultuous development section, Dulcinea appears first. As the composer pointed out, “that inversion is required by the novel’s own trajectory.” Gombau called this work “an epic poem after Conrado and Strauss,” acknowledging his debt to the great European symphonic tradition but also to the nationalist trend in Spanish music.

Gerardo Gombau: Don Quixote keeping vigil over his armor (Madrid Community Orchestra; Jose Ramon Encinar, cond.)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter