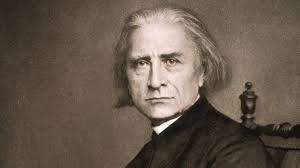

Franz Liszt

It might not be a complete surprise, but Franz Liszt and Felix Mendelssohn really didn’t like each other! Mendelssohn first heard a Liszt performance at a concert in Paris in 1825. In his opinion “Liszt had many fingers but few brains, but his improvisations were absolutely wretched.” As Mendelssohn subsequently wrote to Moscheles, “Liszt is a true artist whom you can’t help liking even if you disagree with him. The only thing he seems to me to lack is a true talent for compositions, I mean original ideas.” They first met face to face in 1831, and Liszt wrote to Marie d’Agoult, “Mendelssohn draws wonderful sketches, plays the violin and the viola, can read Homer fluently in Greek and speaks four or five languages.”

Felix Mendelssohn

But it was the 1825 concert in Paris that had originally soured the relationship. Liszt reports “Mendelssohn, on one occasion, drew a picture on a blackboard of the devil playing his G minor concerto with five hammers on each hand instead of fingers. The truth of the matter is that I once played his Concerto in G minor from the manuscript, and as I found several of the passages rather simple and not broad enough, if I may use the term, I changed them to suit my own ideas. This, of course, annoyed Mendelssohn, who, unlike Schumann or Chopin, would never take a hint from anyone. Moreover, Mendelssohn, although a refined pianist, was not a virtuoso, and never could play my compositions with any kind of effect, his technical skill being inadequate to the execution of intricate passages. So the only course laid open to him, he thought, was to vilify me as a musician.”

It seems, however, that Liszt managed to get his revenge. He tells the story that he met Mendelssohn at dinner at the Comtesse de P’s in Paris. “Mendelssohn had been unusually witty and vivacious at dinner, and after dessert the Comtesse asked him if he would favor us with one of his last Songs without Words, or anything he might find appropriate. Mendelssohn most graciously condescended to sit down at the piano, and to my astonishment, instead of treating us to one of his own compositions, he commenced my Rhapsody No. 4, which he played so abominably badly, as regards both the execution and the sentiment, that most of the guests, who had heard it played by myself on previous occasions, burst out laughing. Mendelssohn, however, got quite angry at their mirth, and improvising a finale after the thirtieth bar or so, dashed into his Capriccio in F-sharp minor, No. 5, which he played through with elegance and a certain amount of respect. At the conclusion we all applauded him.”

And then it was Liszt’s turn at the piano, as Mendelssohn begged him to play something new and striking. Liszt, however, was determined to get his revenge and have some fun at Mendelssohn’s expense. “So I seated myself at the piano,” Liszt reports, “and announced that I would perform the Mendelssohn Capriccio, Op. 5, arranged for concert performance by myself. In a second the guests had comprehended that I intended to avenge Mendelssohn’s butchering of my poor Rhapsodic, although I suppose many thought it a rather hazardous attempt to play a difficult composition in a new garb or arrangement on the spur of the moment, especially with the composer sitting within two yards of the keyboard. However, I did what I had announced to do, and at the conclusion, Mendelssohn, instead of bursting out with indignation and rage at my impudence and liberty, took my right hand in his, and turned it over, backward and forward, and bent the fingers this way and that, finally remarking laughingly that since I had beaten him on the keyboard, the only way of vindication was to challenge me to a boxing match. However, since he had now examined my hand, he would have to abandon that particular course of action. So everything passed over smoothly, and what might have been a very unpleasant meeting turned out a most enjoyable evening.”

Felix Mendelssohn: Scherzo a capriccio in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 5, MWV U 50 (Doomin Kim, piano)

Great Anecdote. It’s nice to peek back at a snippet of history. Mendelssohn wrote very nice music in the classical mode, while Liszt indeed hurled his lance into the future. This comparison was like a horse & buggy rider compared to an astronaut. But very amusing, thanks for posting this!

However, Liszt clearly admired some of Mendelssohn’s pieces as he transcribed quite a lot of the songs and also wrote a Concert Fantasy on the “Songs without words” for 2 pianos.

Seems that Liszt admired everyone else’s music and very few admired Liszt’s. For a reason.

Liszt’s music is beloved and admired by generations of musicians, and Liszt was kind to others like Mendelssohn, even if he didn’t love their music. Liszt was way more innovative than Mendelssohn, and far more interesting, in my opinion. But Mendelssohn was conservative and was hard on people like Liszt and Berlioz, a massive genius whose music Mendelssohn didn’t like because it wasn’t in the old forms.

Its fantastic as your other articles : D, thankyou for putting up.

I have a difficult time believing this anecdote – at least based on the details provided. Listen to Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody #4, particularly the first 13 bars – for an able pianist, it is not that difficult to play. The real virtuosic parts of the rhapsody do not come in until around bar 24 or so. I have a hard time believing Mendelssohn, who was very popular as a performer, couldn’t play those first thirteen bars. Indeed, there is another anecdote, given not by Liszt himself (who was known to be an egomaniac), but by Max Muller, a philologist, amateur musician, and friend of Mendelssohn.

Muller tells us the following story: “Well, Liszt appeared in his Hungarian costume, wild and magnificent. He told Mendelssohn that he had written something special for him. He sat down, and swaying right and left on his music-stool, played first a Hungarian melody, and then three or four variations, one more incredible than the other. We stood amazed, and after everybody had paid his compliments to the hero of the day, some of Mendelssohn’s friends gathered round him, and said : ‘Ah, Felix, now we can pack up. No one can do that ; it is over with us.’ Mendelssohn smiled ; and when Liszt came up to him asking him to play something in return, he laughed and said that he never played now ; and this, to a certain extent, was true. He did not give much time to practising then, but worked chiefly at composing and directing his concerts. However, Liszt would take no refusal, and so at last little Mendelssohn, with his own charming playfulness, said : ‘Well, I’ll play, but you must promise me not to be angry.’ And what did he play ? He sat down and played first of all Liszt’s Hungarian melody, and then one variation after another, so that no one but Liszt himself could have told the difference. We all trembled lest Liszt should be offended, for Mendelssohn could not keep himself from slightly imitating Liszt’s movements and raptures. However, Mendelssohn managed never to offend man, woman, or child. Liszt laughed and applauded, and admitted that no one, not he himself, could have performed such a bravura.”

I find it difficult to believe that Mendelssohn – who memorized Beethoven’s symphonies and could play all of them at the piano, who frequently played Beethoven’s sonatas from heart, who was a master of Bach and Handel, who was considered one of the best improvisers and purest musician of that time period, who could play at only one listen a virtuosic piece and variations by Liszt while imitating him – I find it hard to believe he would play “abominably bad” the first 13 bars of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody #4. Maybe I’m understanding the story wrong, but it does not make sense to me.

Agreed, the anecdote’s credibility is indeed dubious. The 4th Hungarian Rhapsody was composed during 1847, the year that Mendelssohn died. The piece is also only published 6 years after its initial composition, so it is highly implausible that Mendelssohn could’ve known about it.

Unless… the anecdote was perhaps attributing to the Magyar dalok (S. 242), of which many of the Hungarian Rhapsodies owed its early versions from.

There were also a few problems with this anecdote; did Liszt mention to the 4th Rhapsody in retrospect, instead referring to the version of the same piece as it existed at the time? If so, then he was talking about S. 242/7 (the first version of the HR4) – which may be quite technically difficult, even for Mendelssohn.

Or perhaps, did he mean something else by this? Perhaps the anecdote also referred to Magyar dalok No. 4 (an extremely facile work – highly unlikely for Mendelssohn to stumble through it), or the fourth Magyar rapszódiák as published in 1847 (which is still part of the Magyar dalok set, thus it is numbered “No. 15”)?

I really can’t tell which one is it for sure.