Concert Overtures proved highly popular with 19th-century audiences. They frequently served, and still do, as musical appetisers for an evening of symphonic splendour. Concert Overtures are self-contained and communicate and carry meanings explained in the titles. As with all program music, that preface or title directs the listener’s attention to the poetic idea, or in Mendelssohn’s case, towards a 14th-century legend.

Felix Mendelssohn: Die schöne Melusine

Beautiful Melusine was born to a mortal father and a mermaid mother. However, she is cursed to take the form of a serpent from the waist down one day each week in punishment for entombing her father in a mountain for his mistreatment of her mother.

Julius Hübner: ‘Die schöne Melusine’ 1844

One day, while she is sitting beside a fountain in “a glimmering white dress, with long waving golden hair, and a face of inexpressible beauty,” a man of nobility discovers her. They instantly fall in love, and she agrees to marriage but under the condition that he vows not to attempt to see her on Saturday when she will go into seclusion. Great happiness envelops the two lovers, and she bore Raymond ten sons. Eventually, Raymond is overcome by curiosity and witnesses Melusine’s bizarre metamorphosis by spying through the keyhole. Once discovered, Melusine is doomed to remain in her mermaid form for eternity. Mendelssohn composed his Melusine Overture as a birthday gift for his sister Fanny in 1834. He decided on the fairy tale subject after seeing Conradin Kreutzer’s opera Melusina the previous year in Berlin. “Kreutzer’s overture,” he writes, “was encored, and I disliked it exceedingly.”

Edward Elgar: Froissart Overture, Op. 19

Froissart

Edward Elgar: Froissart Overture, Op. 19 (New Philharmonia Orchestra; John Barbirolli, cond.)

With his Froissart Overture, Op. 19, Edward Elgar also looked towards the Middle Ages. Jean Froissart was a French-speaking medieval author and court historian from the Low Countries. He wrote a long Arthurian romance and a large body of poetry, both short lyrical forms as well as long narrative poems. His writings “have been recognised as the chief expression of the chivalric revival of the 14th-century kingdoms of England, France and Scotland.” When Elgar was commissioned by the Worcester Festival, the idea for a Concert Overture was suggested by a line from Keats, which Elgar placed at the top of the score and which epitomises the tales of Jean Froissart, the chronicler and historian: “When Chivalry/Lifted up her lance on high.” Froissart turned out to be Elgar’s first major work for orchestra, and press comments following the premiere were generally favourable. Some critics suggested that “the overture would be better described as the impression of a romantic period than the portrayal of any particular sequence of events.” To be sure, Elgar always insisted that the overture does not tell any connected story of action and character. Rather, “it is an expression of feeling inspired by the character and ambience of a place or an age.”

Robert Schumann: Hermann und Dorothea Overture, Op. 136

With Mendelssohn reaching into the treasure trove of legends and fairytales and Elgar exploring the age of chivalry, Robert Schumann took aim at Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s epic poem “Hermann and Dorothea.” Originally, he planned to compose an entire opera, but then changed his mind and was looking to write a Singspiel. Still not convinced, Schumann changed his mind once again and decided to compose an oratorio on the subject. In the end, he only produced an orchestral score—a concert overture—which remained unprinted during his lifetime. Goethe’s poem dates from 1796 and features Hermann, the son of a wealthy innkeeper in a small town near Mainz. He is sent by his mother to bring provisions to refugees in a camp near their town. They have fled their villages on the western side of the Rhine River, now occupied by French revolutionary troops, to seek refuge on the eastern side. Hermann meets Dorothea, a young maid assisting a woman in childbirth during her flight. Hermann is overwhelmed by her courage, compassion and beauty, but when he confesses his attraction to this father, he is sternly lectured. His mother, however, takes her husband to task:

Hermann und Dorothea

Why will you always, father, do our son such injustice?

That least of all is the way to bring your wish to fulfillment.

We have no power to fashion our children as it suits our will;

As they are given by God, so we must have them and love them;

teach them as best we can, and let each of them follow his nature.

Predictably, all ends well when Hermann’s father grudgingly agrees to the marriage. Schumann’s overture carries the unofficial subtitle “Revolutionary Overture” precisely because of his striking thematic use of the “Marseillaise.”

Hector Berlioz: Overture to Les francs-juges

Once Hector Berlioz had abandoned his medical studies, which immediately sparked condemnation from his entire family and the curtailment of funds, he began to attend the Parisian Conservatoire in 1826. Officially, he studied composition with Le Sueur, something he had privately done for some time. One of his projects was to be a three-act lyric drama titled Les Francs-Juges. The work was never completed, and much of the music was destroyed or later recycled. The libretto takes its name from the secret courts of medieval Westphalia in Germany. In Berlioz’s plot, self-appointed judges who commit murder and usurpation to retain authority over the realm control the evil King Olmerik. The rightful king, Lenor, is in love with Amelie, who is betrothed to Olmerik. When Lenor appears in front of the menacing judges, he condemns Olmerik and is promptly sentenced to death. However, before the sentence can be carried out, the good citizens and enlightened peasants save his life and his rightful reign is restored, with love conquering all. The opera was never staged nor published, but the overture found a home in the Concert Hall. Importantly, Berlioz conducted it more frequently than any of his compositions and considered it his first orchestral work worth publishing.

Arthur Sullivan: Overture di Ballo

Let’s lighten the mood a little and turn to the Overture di Ballo by Arthur Sullivan. Sullivan’s overtures to HMS Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado and The Yeomen of the Guard introduced comic operas that were created in collaboration with William Gilbert as librettist.

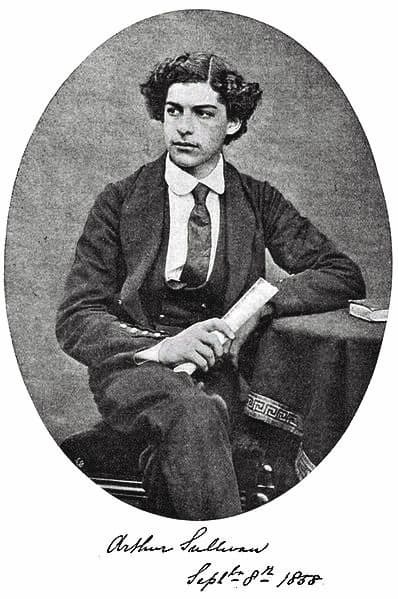

The young Arthur Sullivan, age 16

However, the Overture di Ballo dates from 1870, the year he met William Gilbert for the first time. Sullivan had studied in Leipzig under Julius Rietz and Carl Reinecke, with Edvard Grieg as a classmate. Once back in England, he received a commission from the 1864 Birmingham Festival. The cantata The Masque at Kenilworth proved successful, and the Birmingham authorities approached him again in 1869. This time, they were looking for an orchestral overture for the 1870 Festival. Sullivan squabbled over his fees and did not start work until mid-May 1870. The title is somewhat confusing as it combines the English word “overture” with the Italian “di ballo.” Sullivan appears to have favoured “Overtura di Ballo,” but that also makes little sense. In the event, the overture does “combine grace and sparkle with memorable tunes and rhythms.” Sullivan wrote to his mother after the premiere, “The Overture was a great success last night, and on the strength of it, they are to have my portrait in the local illustrated paper tomorrow with a short notice. It went beautifully, and everyone who spoke to me seemed delighted.”

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36

In his Russian Easter Festival Overture Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov combined his gift for brilliant orchestration with a heightened interest in Eastern culture. Composed between 1887 and 1888, this concert overture was part of a series of dazzling orchestral showpieces that included the Capriccio Espagnol and Scheherazade. Dedicated to the memories of Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov aimed to reproduce “the legendary and heathen aspect of the holiday, and the transition from the solemnity and mystery of the evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious celebrations of Easter Sunday morning.”

Russian Easter Eggs

In essence, Rimsky-Korsakov musically encoded his childhood memories, growing up in Tikhvin, in Novgorod province. Korsakov remembers the celebration of Easter, also called “Bright Holiday” in Russia, as a large gathering of “people from every walk of life, with several popes conducting cathedral service…the old liturgical chants and nearby monastery bells ringing out.” The Russian Easter Festival Overture is entirely based on chants used in the Orthodox Church. Rimsky-Korsakov suggested, “a great deal in my music is not mine.” Be that as it may, the Russian Easter Festival Overture nevertheless captures the unique spirit of Russian culture and music.

Eliott Carter: Holiday Overture

Elliott Carter

Eliott Carter: Holiday Overture (Odense Symphony Orchestra; Donald Palma, cond.)

For many Christians around the world, Easter is one of the most important religious holidays. The Holiday Overture by Elliot Carter, however, has no overt religious connections. In fact, it was composed on commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra to celebrate the liberation of Paris during World War II. Carter had spent three years in Paris, and his overture reflects the general uplifting spirit of most American concert music composed then. While the overture harbours similarities with the music of Aaron Copland, according to the composer himself, the work was also one of his first to use “consciously the notion of simultaneously contrasting layers of musical activity.” In addition, Carter has said of the work, “…it was to be a demonstration of brilliant orchestration, and a lively, good-spirited sort of piece.” While this overture was to celebrate German defeat, it ironically received its first performance in Germany.

Winner of the 1945 Independent Concert Music Publisher’s Contest, which was to have ensured a Boston Symphony première under Koussevitzky, the overture was instead first performed in Frankfurt under Celibidache. It finally sounded on American soil, in revised form, with the Boston Symphony in 1961.

Antonín Dvořák: Carnival Overture, Op. 92

In the mid-1880s, Antonín Dvořák suffered what we would call a mid-life crisis. He was very happily married, had nine children, was financially very secure, and had reached the pinnacle of his international fame professionally. So why was he so unhappy? Well, for one, he was severely criticised by Czech music critics for failing to aggressively promote Czech rights within the German-dominated Habsburg Empire.

Also, his compositions were published less in Bohemia than in foreign lands because he was perceived as a cosmopolitan composer using an international musical language that imitated his hero, Johannes Brahms. Essentially, it all came down to a question of cultural and personal identity. After a period of deliberation, Dvořák came to the conclusion that he always was and always would be a simple country composer from Bohemia. As a result, his aesthetic conception and his musical language changed; it became more outspoken, more deliberate, more descriptive and more nationalistic, with much of his inspiration now taken from the natural beauty and the dance rhythms and folk-music influences of his homeland. With this new approach in mind, Dvořák composed three orchestral overtures, originally titled “Nature, Live and Love.” Eventually, he changed the titles to “In Nature’s Realm, Carnival and Othello.” Dvořák himself described the story behind his Carnival Overture, Op. 92. “The wanderer reaches the city at nightfall, where a carnival of pleasure reigns supreme. On every side is heard the clangour of instruments, mingled with shouts of joy and the unrestrained hilarity of people giving vent to their feelings in the songs and dance tunes.”

William Walton: Portsmouth Point Overture

Portsmouth Point, or “Spice Island”, is part of Old Portsmouth in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the southern coast of England. The name Spice Island comes from the area’s seedy reputation, as it was known as the “Spice of Life.” William Walton decided to compose a concert overture after viewing a print of that area by the seventeenth-century satirist Thomas Rowlandson. Rowlandson’s print depicts a scene of hectic and often bawdy activity on the quayside, and Walton’s music celebrates the rowdiness and vitality rather than some of the darker undercurrents, which can be seen in the print’s details. Composed in 1925, Walton recalled that the main theme had come into his mind whilst riding on a route 22 Bus in London. Much of the composing, however, was done on a trip to Spain. The overture was selected for performance at the 1926 International Society for Contemporary Music Festival and received its first performance in Zürich on 22 June 1926. Commentators have noted the influence of Igor Stravinsky’s music and jazz in the rhythms of the score. As overtures for the concert halls go, it is still a raucous and joyous musical appetiser for an exciting evening with the orchestra.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter