Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky composed well over 100 romanzas written for voice with piano accompaniment. These songs enjoyed considerable popularity, however they also attracted some criticism. The Russian composer and music critic César Cui, for example, denounced them for failing to respect the literary values of the words they set. I read somewhere that Tchaikovsky considered “music a form of truth beyond verbal language.”

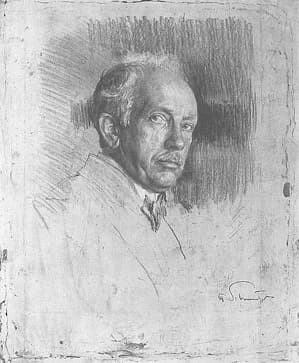

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky was an avid reader and he also wrote poems not intended to be set to music.

Of course, he also composed songs to his own lyrics, and his romances are a kind of diary expressing love, euphoria, loneliness, deception, restlessness, impatience, grief, despair, remorse, hopelessness, nostalgia and longing.

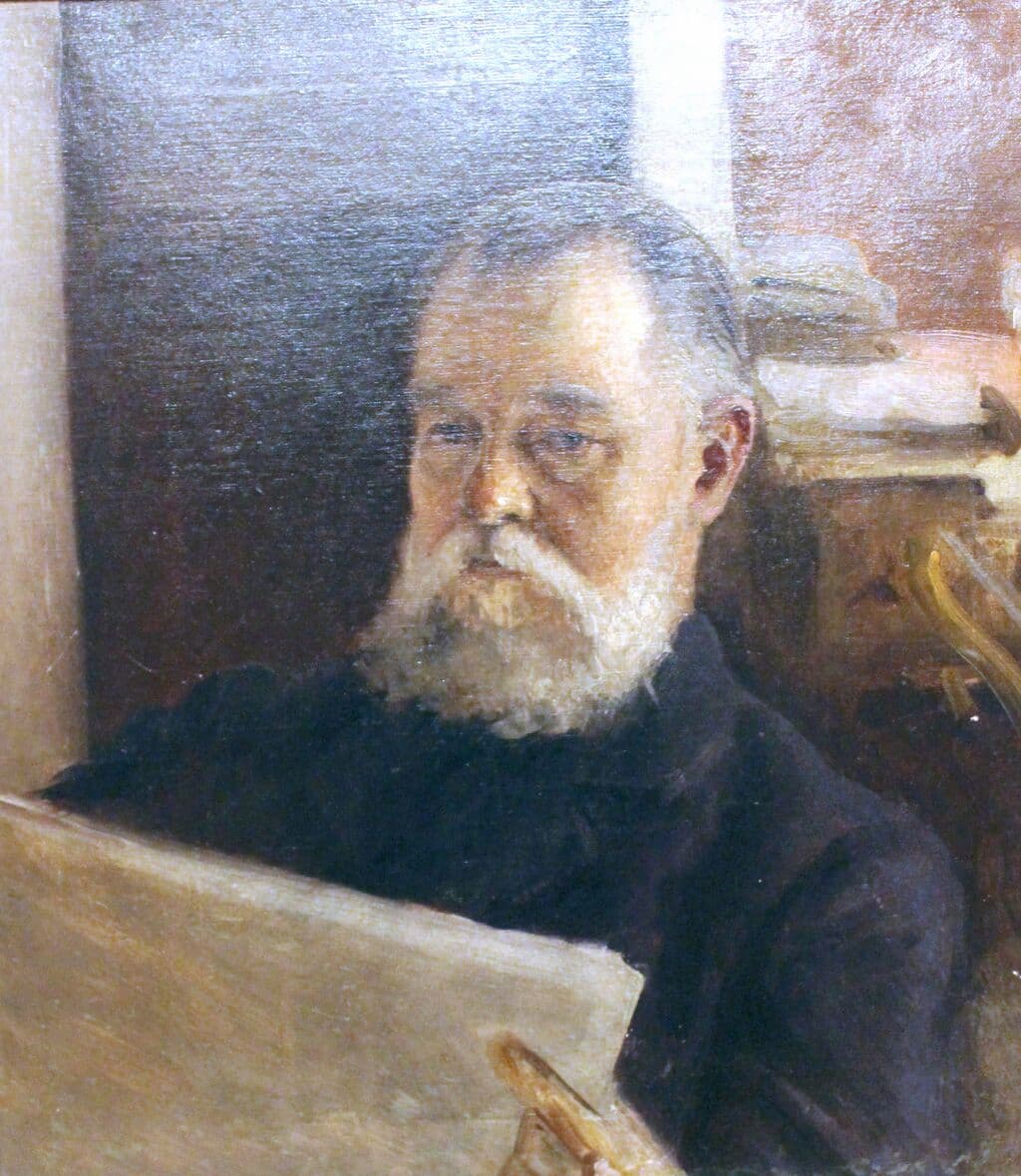

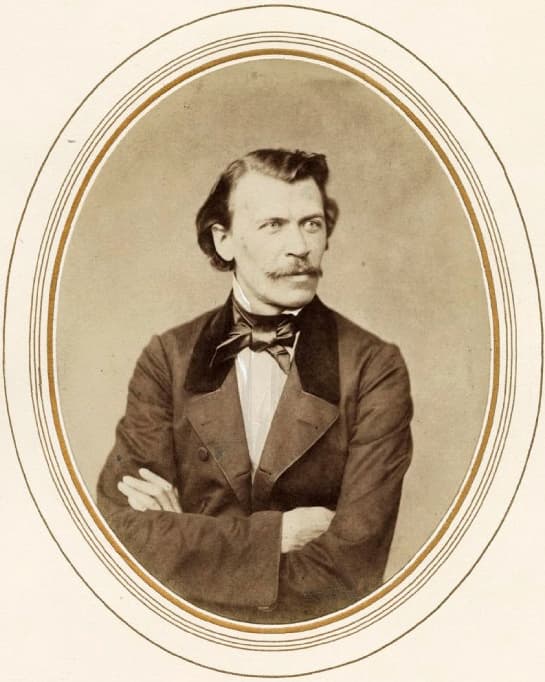

Pyotr Jurgenson

Perhaps surprisingly, Tchaikovsky did not object to producing instrumental arrangements of his romanzas. In fact, he even commissioned transcriptions from colleagues, which he revised and published with his lifelong publisher and friend P. Jurgenson. Since Tchaikovsky basically sanctioned transcriptions of his songs, and since the Russian language is a mouth and earful for performers and listeners, many beautiful arrangements have been produced. So, let’s listen to 10 Unforgettable Tchaikovsky Melodies in exotic dresses.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 6, No. 2 “Not one word, O my friend” (A. Krein, piano trio) (Ilona Then-Bergh, violin; Wen-Sinn Yang, cello; Michael Schäfer, piano)

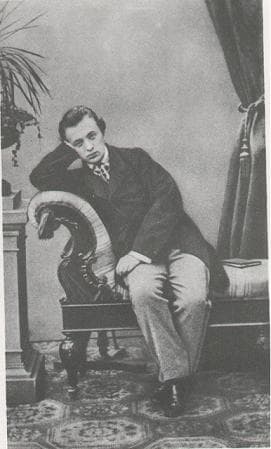

Alexander Krein

In 1912, the publisher P. Jurgenson set out to commission an anthology of music that represented a cross-section from the Golden Age of Russian music. He hired the Russian Jewish composer Alexander Krein (1883-1951) to select a cycle of 25 masterpieces by Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov, Scriabin, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky and others. Titled “The Soul of Russia,” Krein produced a cycle based on the year of composition, key, and genre, and all the music is arranged for piano trio.

Krein selected Tchaikovsky’s Six Romances Op. 6 for his transcription, a collection that is all about the suffering experienced after the loss of a loved one. Three of the songs were based on Germany poems, but Tchaikovsky used Russian translations. Clearly, the young composer was looking to appeal to Russian audiences. The second song of Op. 6 “Not one word” is a poem by the Austrian writer Moritz Hartmann, and it is dedicated to the composer’s friend Nikolay Kashkin, who taught at the Moscow Conservatory. The short musical phrases, with the words removed, convey an even greater sense of drama, don’t you think?

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 6, No. 3 “It is both painful and sweet” (J. Nagel, solo piano) (Julia Severus, piano)

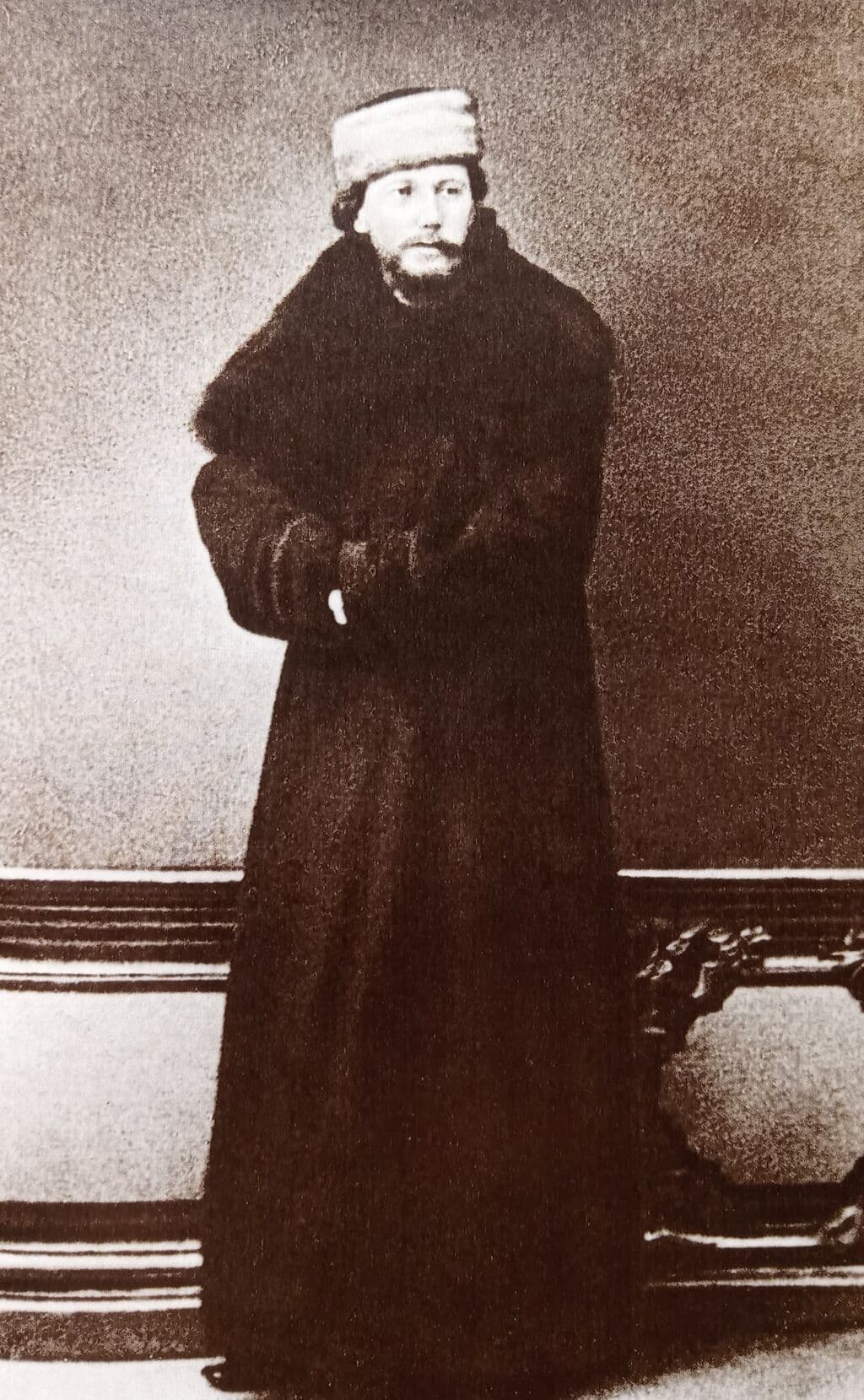

Tchaikovsky, 1866

Tchaikovsky considered 2 of his Op. 6 Romances, the Nos 3 and 6, to be his most popular songs. The composer sought to expand this popularity by commissioning arrangements from colleagues, including the German-born cellist, pianist and composer Julius Nagel. Nagel was a graduate of the Leipzig Conservatory and he emigrated to Russia in 1862. He quickly found employment at the Imperial Alexander Lyceum in St Petersburg.

Eydokiya Rostopchina

Nagel had some success with his operas Tranello and The Psychic in Gotha, but he made his name in Russia with countless pieces and transcriptions in the “Nuvellist” journal. “Both painfully and sweetly,” the third romanza of the set originally uses a text by Eydokiya Rostopchina. The poem details the anguish of an anticipated love affair and the relief of parting without having spoken a word. Nagel’s transcription emphasises the operatic character of the music as it was not intended as a showpiece for the pianist. Just a beautiful poetic miniature unfolding over time.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 6, No. 6 “None but the Lonely Heart” (M. Maisky, cello and piano) (Mischa Maisky, cello; Pavel Gililov, piano)

Mischa Maisky © Deutsche Grammophon

The one art song that earned Tchaikovsky international fame also originates in his Op. 6 Romanzas. “None but the Lonely Heart” is performed in recitals and concerts around the world. The original German text is by Goethe, and it is one of the earliest Tchaikovsky compositions that reveals his distinct personal style. The yearning melody and that beautiful melancholic tone would become one of the hallmarks of Tchaikovsky’s musical style.

Cellist Mischa Maisky has courted some controversy for arranging music originally not written for the cello. He once explained, “most of the great composers were more open-minded in this respect than many people today.” Arranging and transcribing, according to Maisky, helps people discover and enjoy some music which they otherwise will not hear, and “I try to only arrange the music that shows the best qualities of the cello as an instrument.” In my personal opinion, Maisky has done a wonderful job in his revoicing of this particular Tchaikovsky Romanza.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 38, No. 3 “Amid the Din of the Ball” (P. Breiner, violin and orchestra) (Takako Nishizaki, violin; Queensland Orchestra; Peter Breiner, cond.)

Tchaikovsky and his wife Antonina Miliukova

Antonina Milyukova confessed herself to be hopelessly in love with Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky in 1877. Since Tchaikovsky was known for his numerous affairs with his male students, this surprise marriage to his female student was really a shocker. It didn’t go well, as Tchaikovsky was so horrified by his wedding night that he tried to drown himself. Around the same time, he decided to leave the Moscow Conservatory, a move made possible by Nadezhda von Meck, who offered him a pension. He spent time at Meck’s country estate in Brailov, and he wrote the songs of Opus 38. Probably the most famous of the set is the poignant waltz-song “Amid the Din of the Ball.”

Tchaikovsky’s beautiful melancholic melodies really come to life when played by the violin and supported by orchestra. And when it comes to arrangements of this kind, the first name that comes to mind is Peter Breiner. He started piano lessons at the age of four and was admitted for formal training at the Conservatory in Kosice. Breiner is an all-around musical talent as he is also a composer, conductor, and arranger. He speaks seven languages and hosted various TV and radio programs about music. And his arrangement of the Op. 38, No. 3 Romanza is truly sublime.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: Six Pieces, Op. 51, No. 5 “Romance”

So far, we have been listening to transcriptions and arrangements of Tchaikovsky’s vocal music, particularly his romanzas. However, the composer also wrote solo piano pieces with that particular title. In 1882, an editor asked him to write six pieces for piano, “four of them should have the titles Nocturne, Dreams, Salon Waltz and Russian dance.” It all got a little complicated because Tchaikovsky was under contract with a different publisher. And once his regular publisher asked for some piano pieces, the composer declined.

Nadezhda von Meck

He wrote to Tchaikovsky, “you recently declared how you had profited by selling me no fewer than 6, 12, 24 piano pieces… Naturally I would not wish that your muse should be awakened just for financial reasons.” In the meantime, Tchaikovsky was busy with other projects, but eventually, he supplied “6 Pieces for piano.” And the No. 5 of the set turned out to be a beautiful instrumental romanza.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 7 Romances, Op. 47, No. 6 “Whether Day Dawns” (G. Zaborov, voice, string ensemble, piano) (Anatoli Solovyanenko, tenor; Siberian Violinists Ensemble; Rita Bobrovich, piano; Mikhail Parkhomovsky, cond.)

Aleksey Apukhtin

Tchaikovsky and Aleksey Apukhtin (1840-1893) were close friends and classmates. The young Tchaikovsky looked up to his new friend as being far more talented and knowledgeable in literature, and Apukhtin recognised his friend’s artistic aspirations. He even dedicated a poem to Tchaikovsky in 1877:

“You remember how, hiding in the music room,

Forgetting school and the world, We would dream of an ideal glory — Art was our idol,

And life for us was fanned by dreams…”

It’s hardly surprising that Tchaikovsky would select his friend’s poetry for a number of musical settings. And that includes “Whether day dawns,” contained in the set of Romances Op. 47. Tchaikovsky thought highly of his setting and subsequently arranged it for soprano and orchestra in 1888. That particular version has regrettably been lost, but Grigory Zaborov, the concertmaster of the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, might well have taken Tchaikovsky’s arrangement as the starting point for his own creation.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 38, No. 6 “Pimpinella” (D. Benko, 2 guitars) (Daniel Benko, guitar)

Tchaikovsky travelled to Florence in the Spring of 1878. He was accompanied by his brother Modest and Nikolay Konradi. Nikolay had been born without the ability to hear or speak, and Modest was engaged to tutor the young body. Under Modest’s guidance, Nikolay learned to talk, write and read in three languages, and he was educated to graduate level. The trio visited the Uffizi Gallery, Palazzo Vecchio, Basilica di San Lorenzo, and the Muzeo Nazionale. And in his spare time, Tchaikovsky worked on the Twelve Pieces, Op. 40 for piano, and his Six Romances Op. 38.

Shortly before departing Florence, Tchaikovsky writes, “I had a meeting with the boy singer…I completely surrendered myself to the anticipation of our dear boy’s singing. First of all, I noticed that he was handsome, and it is impossible to describe what happened to me when he started to sing.. I wept, languished, melted with delight. Besides the song you know, he sang two more, one of which, Pimpinella, was lovely.” Moved and charmed by the song, Tchaikovsky noted down the melody together with the words and later provided his own Russian translation. With the melody and words originating in Florence, it is only fitting that the featured arrangement utilises two guitars. It really accentuates the Florentine musical flavour.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 6 Romances, Op. 16, No. 1 “Cradle Song” (S. Rachmaninoff, piano) (Idil Biret, piano)

Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1892

Transcriptions and arrangements familiarised the public with the latest and hottest musical items on the market. And predictable, such re-working could turn into money spinners. Tchaikovsky fashioned his own arrangements, but he also commissioned students and colleagues. In fact, he officially commissioned the young Sergei Rachmaninoff for a four-hands piano arrangement of Sleeping Beauty. To make a long story short, Tchaikovsky hated the Rachmaninoff effort, charging that it “lacked in courage, initiative and creativity!!!”

At the time of the arrangement, Rachmaninoff was only 18 years of age, but he always considered the act of transcribing a satisfying compositional experience rather than a pure exercise in piano reduction technique. Always brilliant in sound and supremely expressive, this expressiveness is realized through his own complex and distinctive harmonic language. In addition, counterpoint plays a substantial role in all his transcriptions. As a pianist writes, “from a performance point of view, important features of Rachmaninoff’s approach are contained in the composer’s use of acoustical qualities of the instrument and the factors that influence aural perception of a melodic line and its elements.” Rachmaninoff beautifully drapes Tchaikovsky’s “Cradle Song” in his characteristic harmonic cloak.

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 12 Romances Op. 60, No. 9 “Night” (P. Tchaikovsky, chorus, piano) (Moscow Academy of Choral Singing; Tamara Kravtchenko, piano; Victor Popov, cond.)

Yakov Polonsky

Tchaikovsky left a considerable output of secular choral music written for a variety of ensembles, including male, female, and mixed. He would occasionally feature one or more soloists, usually “a capella,” but in some cases with piano accompaniment. However, he did not only compose original choral music but also arranged a number of his romanzas and vocal duets for choir and piano accompaniment. Such is the case with his Romanza Op. 60, No. 9 to a poem by Yakov Polonsky. The poetic sentiment of the clear night, inviting the listener to forget the troubles of the world and fall asleep in restful peace, is beautifully mirrored in the staggered entrances of the voices.

Leopold Stokowski

The conductor Leopold Stokowski is world-famous for his appearance in several Hollywood films, most notably in Disney’s Fantasia. Stokowski had a long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and he was known as a musical showman. He would through his conducting score into the air to show that he did not need to conduct with music in front of him, and he also started conducting without a baton. Stokowski is also credited as the first conductor to adopt the seating plan as it is used by most orchestras today, with first and second violins together on the conductor’s left, and the violas and cellos to the right.

Stokowski produced a substantial number of transcriptions and arrangements, with Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor transcribed for symphony orchestra probably his most famous. And Stokowski also took on the music of Tchaikovsky, bringing Romanza Op. 73, No. 6 to an audience with different acoustic expectations and habits of hearing. With audiences in Philadelphia not used to hearing Russian lyrics that might distract from Tchaikovsky’s beautiful melodies, Stokowski communicated a modernised version that masterfully used the resources of the entire orchestra.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky: 7 Romances Op.73, No. 6 “Again, as before, alone” (L. Stokowski, orchestra) (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; José Serebrier, cond.)