Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was a master of orchestration and his 1844 book on the subject was the standard not for years, but for decades after his death. He lived his life with his heart on his sleeve and works such as the Symphonie fantastique laid out his (supposed) life as a romantic: experiments with mind-altering drugs, the floating sound of his beloved, and then, at the end, the bad trip. The penultimate movement that ends in his death at the scaffold, and then the final movement of a witches’ sabbath is unequalled even today.

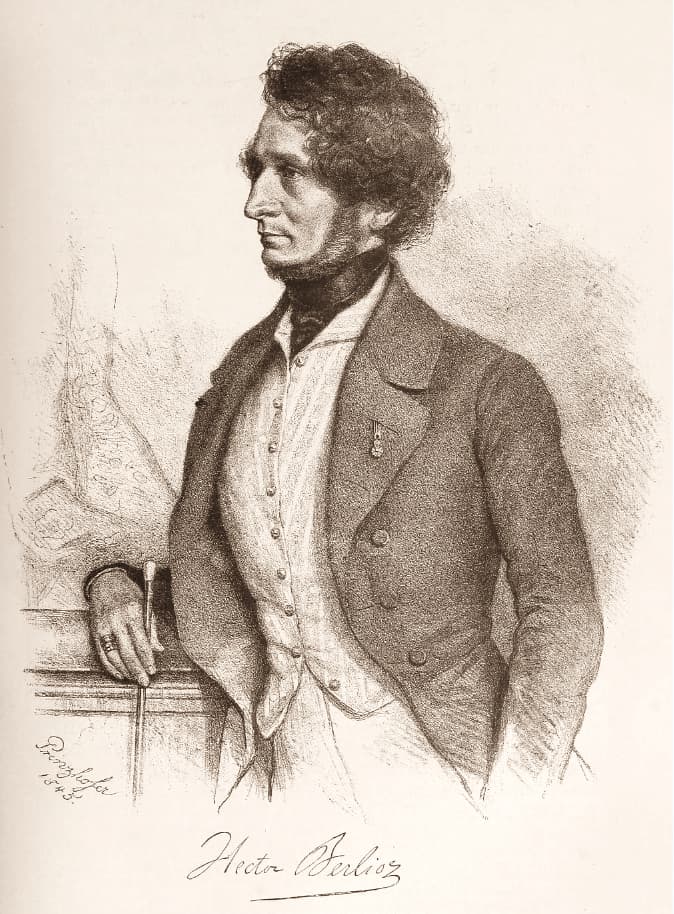

August Prinzhofer: Hector Berlioz, 1845

His first full-length opera, Benvenuto Cellini, about the famous Italian sculptor and goldsmith, was based on a real person but with a totally fictitious plot set in Rome, rather than in Cellini’s native Florence. He started the opera in 1836, had its Paris premiere scheduled for June 1838, had it postponed, and finally performed at the Paris Opéra on 10 September 1838.

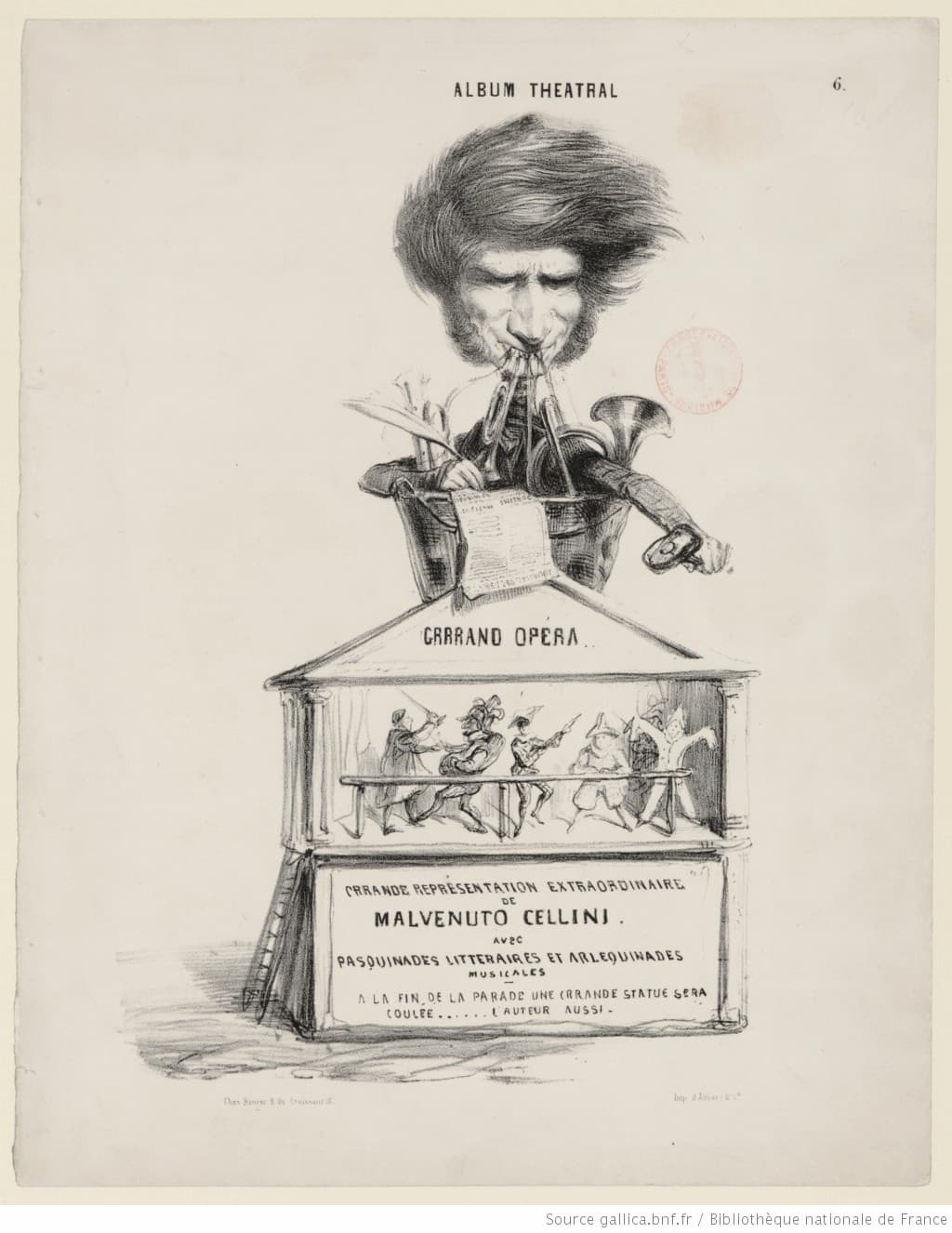

It was not a success. The audience hissed its way through most of the music after the beginning. It closed after 3 performances. The censors demanded changes, Berlioz made them, but the opera was still not a success. Liszt got involved and did a revision of the work for Weimar, but the lead singer was on his career decline. Not a success. When it went to London in 1853, it was yet again not a success.

French cartoonists immediately started calling it MALvenuto Cellini.

Banger: Hector Berlioz, 1837 (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b8415753f)

What could be rescued from the wreckage?

In 1844, Berlioz took the saltarello that was used to end Act I and used it as the heart of a new work.

Hector Berlioz: Benvenuto Cellini, Op. 23 (Weimar version) – Act I, Tableau II Scene 13: Venez, venez peuple de Rome (London Symphony Chorus; London Symphony Orchestra; Colin Davis, cond.)

In the opera, the saltarello is the last dance of the night before the cannon sounds from the Castel Sant’Angelo signalling the end of Carnival and the start of the austerity of Lent. And the end of Act I.

His new work was The Roman Carnival Overture, now considered a tour-de-force of orchestration. It was intended as a stand-alone concert overture and in some London productions in the 1850s was used as an overture to the second act, thus coming full circle to rejoin the opera.

Hector Berlioz: Roman Carnival Overture, Op. 9 (West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Wand, cond.)

The Overture is exciting, removing the chorus from the saltarello means that the orchestra can play to its own speed, with no slow singers in the way. Berlioz opens with a soulful English horn solo and builds, gradually, to that triumphant final chord. Every orchestral voice has its place in the spotlight and the work gradually is dressed in its own drama. He uses two cornets, which could lay chromatically instead of the natural trumpet which could only play overtone series. Trombones are reserved for the end. Percussion is focused on the light end: cymbals, tambourine, and triangle, and no bass drum.

The slow theme comes from a love duet in Act I of Benvenuto Cellini, but it’s that roaring saltarello that we come away with, it lodged indelibly in our memory. The saltarello, which Berlioz would have encountered in Italy (we’ll note Mendelssohn also used the saltarello in his Italian Symphony), and here, with cymbals and tambourines punctuating the rise and fall of the melody, we finally have the love melody combine with the dance melody and a grand explosion of sound, energy, and colour at the end.

As you can hear from the two examples above, the Overture is a better piece than the original. The music is developed more colourfully and there’s more variation. He changes the key from the original as well. The return of the slow love song is a surprise, as is its combination with the whirling dance. Berlioz knew the music from Benvenuto Cellini had value and in The Roman Carnival Overture he showed what he could do without the strictures of opera.

The opera itself didn’t get consistent performances until the 20th century, having revivals starting in the 1950s, and then, with recordings being made, it had greater exposure. It was part of the critical edition in the New Berlioz Editions in the 1900s and this went a long way in solving the various versions (Paris, Paris II after the censor, Weimar, etc.). The 21st century has given us new productions in New York under Levine, Salzburg under Gergiev, London at the English National Opera, a production in Amsterdam, and one at Versailles. Malvenuto is now Benvenuto and we all want to go dance at the Carnival!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter