Fanciful sketch by Marguerite Martyn of a New Year’s Eve celebration, 1914

It’s time to say good riddance to 2021 as we hopefully look forward to a more upbeat 2022. The changing of a calendar year, regardless of culture, nationality or creed has traditionally been cause for celebrations. Expressions of exuberance include singing, eating, drinking, dancing, fireworks, and a sense of spiritual renewal. Seemingly, for a short period of time humanity decides to deliberately forget about its worries and troubles.

Eduard Mörike

And not surprisingly, music plays an important role in many of these New Year’s celebrations. In much of the English-speaking world, the words of a Scots poem “Auld Lang Syne,” probably best translated into modern English as “long, long ago” is used to bid farewell to the old year at the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve. Celebrations in London, at Time Square in New York, or in other major cities tend to be very public and boisterous affairs, however, the arrival of a new year is also celebrated in more private and intimate contexts. The German Romantic poet and author of novellas and novels Eduard Mörike (1804-1875), for example, penned a touching poem titled “To the New Year.”

So quietly, lowly

Like angels that slowly

Aurorally winged

Set foot on the earth,

Thus morning drew nearer.

Welcome godfearing

With joy its appearing!

Its holy appearing,

Heart, welcome with mirth!

In Him all beginning

Who reigns, ever spinning,

The moons’, suns’ and planets’

Celestial parade.

You, Father, you counsel!

Be guide and defence!

Lord, into Thy hands

Beginning and end,

The whole world be laid.

(English translation © Bertram Kottmann)

Hugo Wolf: Mörike Lieder, No. 27 “Zum Neuen Jahr” (Magdalena Kožená, mezzo-soprano; Christian Schmitt, organ)

Hugo Wolf, 1902

During his short life, Mörike was really only known to a small literary circle in southern Germany. The first edition of his poems was issued in 1838, and initially it did not sell well. However, since his mostly lyrical poetry was written in simple and seemingly everyday German, it eventually attracted high praise. As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein remarked, “Mörike is really a great poet and his poems are among the best things we have…the beauty of his work is very closely related to Goethe’s. The great Lieder composer of the day, including Robert Schumann, Robert Franz and Johannes Brahms were not really familiar with Mörike’s work, and only infrequently consulted him for texts. As such, it was left to Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) to deeply penetrate the poetic world of Mörike, and to transpose his lyricism into music. Wolf discovered Mörike’s poems in 1878, three years after the poet’s death. It took the composer roughly another decade to find the keys to the “complex, iridescent world of Mörike, a world that passed through all the meandering of the human soul: the pleasures and pangs of love, irony and caricature, frightening fantasy and charming grace, faith and sensuality. Expressing this world in music created the necessity for novel means of expressions, broaching the stylistic solutions that a priori seemed the preserve of Richard Wagner.”

Gabriel Rheinberger: 5 Lieder, Op. 31, No. 4 “Zum Neuen Jahr” (Europa Chor Akademie; Joshard Daus, cond.)

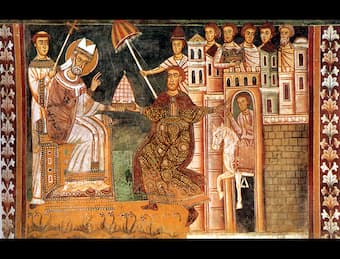

Pope Sylvester and Emperor Constantin

Mörike is also credited with a delightful story about the legend of Sylvester and the New Year. You see, in German-speaking countries New Year’s Eve is known as “Sylvester,” as it celebrates the feast day of Pope Sylvester I. He died on 31 December 335 and played an important role in the history of the Western Church by founding and building a number of large churches in Jerusalem and Rome. According to legend, Pope Sylvester cured the Emperor Constantine of leprosy by administering baptismal water. In the Western liturgical year, the feast of Saint Sylvester falls on 31 December, the day of his burial in the Catacomb of Priscilla. In Mörike’s fairytale, the legend of Sylvester and his annual journey to Earth with the New Year comes to life in a wonderful fairytale. On a cold winter’s day, Eduard Mörike takes a walk with the young daughter of his friend. While stumping through the snow he tells her the story of Sylvester, who sleeps all year and only awakens for New Year’s. The story of Sylvester riding his silver moon horses on his annual journey through all the stars of the Milky Way left a lasting impression on the young girl. When she was an adult, she wrote it down and so it has been passed on, thus creating a new tradition of reading this book on New Year’s Eve. Experts are still not sure if that tale actually originated with Mörike, but it certainly is still part of the New Year’s Eve tradition today.

Ida Henriette da Fonseca: Zum Neuen Jahr (Helene Hvass Hansen, soprano; Cathrine Penderup, piano)

When Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) hosted a merry New Year’s party at his house in Weimar in 1802, he was seemingly overcome by poetry. Clearly, Goethe could pull rhymes out of his hat at any time, and “On the New Year” was first published in 1804,

Fate now allows us,

Twixt the departing

And the upstarting,

Happy to be;

And at the call of

Memory cherish’d,

Future and perish’d

Moments we see.

Seasons of anguish,

Ah, they must ever

Truth from woe sever,

Love and joy part;

Days still more worthy

Soon will unite us,

Fairer songs light us,

Strength’ning the heart.

We, thus united,

Think of, with gladness,

Rapture and sadness,

Sorrow now flies.

Oh, how mysterious

Fortune’s direction!

Old the connection,

New-born the prize!

Thank, for this, Fortune,

Wavering blindly!

Thank all that kindly

Fate may bestow!

Revel in change’s

Impulses clearer,

Love far sincerer,

More heartfelt glow!

Over the old one,

Wrinkles collected,

Sad and dejected,

Others may view;

But, on us gently

Shineth a true one,

And to the new one

We, too, are new.

As a fond couple

‘Midst the dance veering,

First disappearing,

Then reappear,

So let affection

Guide thro’ life’s mazy

Pathways so hazy

Into the year!

Robert Schumann: “Sylvesterlied” (New Year’s Song), Album for the Young Op. 68, No. 43 (Leonora Armellini, piano)

Clara Schumann and her children

The union of Robert and Clara Schumann produced eight children, all born between 1841 and 1854. With his family of little musicians steadily growing, Robert began to compile a short album of “Little Piano Pieces” for the seventh birthday of his daughter Marie. And once he had started, new ideas for miniatures came inevitably to his mind. Clara wrote in her diary, “The pieces usually given to children at their piano lessons are so bad, that it has occurred to Robert to bring out a collection of such little works himself.” Determined as always, Schumann finished the 43 pieces of his Album for the Young in barely 2 weeks. “I cannot remember ever feeling as content as when working on these pieces,” Schumann wrote to his friend Carl Reinecke, “I felt as though I were starting to compose all over again!” Schumann subdivided the set up to No. 18 as suitable for “younger players,” and starting with No. 19 as appropriate “for more mature players.” Schumann tellingly wrote, “Never play bad compositions, nor even listen to them, unless absolutely obliged to do so.” His collection of poetic miniatures concludes with the delightful “New Year’s Song!” On the other side of the globe, Yokoi Yayu (1702-1783) was a samurai of high rank in the service of the lord of Owari. He was proficient in classical Japanese poetry, Chinese poetry, painting, and playing the lute-style stringed instrument called the biwa. Yayu also wrote a substantial number of haiku poems, including one dedicated to the New Year. Looking forward to the melting of the snow, it has been lovingly set to music by the Swedish organist and composer Carin Malmlöf-Forssling (1916-2005).

Neujahrstag ist heut!

Wer mir heut den Schnee zertritt,

Soll willkommen sein!

Carin Malmlöf-Forssling: Vollmond (3 Haiku) “New Year” (Margareta Jonth, soprano; Kerstin Aberg, piano)

Rainer Maria Rilke

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) is widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense German-language poets. “He was unique in his efforts to expand the realm of poetry through new uses of syntax and imagery and in an aesthetic philosophy that rejected Christian precepts and strove to reconcile beauty and suffering, life and death.” As literary critics have pointed out, “Where others have found a unifying principle for themselves in religion or morality or the search for truth, Rilke found his in the search for impressions and the hope these could be turned into poetry… For him Art was what mattered most in life.” During the last few years of his life, Rilke was inspired by such French poets as Paul Valery and Jean Cocteau, and wrote most of his verses in French. And that includes the touching “L’année tourne” set to music by Darius Milhaud.

L’année tourne autour du pivot

de la constance paysanne ;

la Vierge et sainte Anne

disent chacune leur mot.

D’autres paroles s’ajoutent

plus anciennes encore, —

elles bénissent toutes

et de la terre sort

cette verdure soumise

qui, par un long effort,

donne la grappe prise

entre nous et les morts.

Darius Milhaud: Quatrains valaisans, Op. 206, No. 3 “L’Année tourne” (North German Radio Chorus; Philipp Ahmann, cond.)

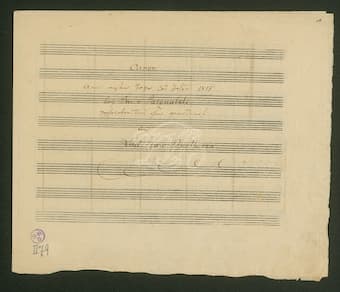

Beethoven: “Glück zum neuen Jahr!” WoO 165

Let us conclude this little survey of Lieder for and about the New Year with a bit of light-hearted fun by Ludwig van Beethoven. Light-hearted fun and Beethoven, I hear you say, generally don’t go together. However, Beethoven left us a number of musical jokes and canons that are probably the least explored areas of his oeuvre. None of these items constitute great music or essential Beethoven, but we find the composer with his shirt left unbuttoned and in a rare jovial mood. In his canons, a reviewer writes, “Beethoven, for all his childish unpredictability and irascibility, could also be affectionately childlike, and, above all, good company.” And that is certainly the case in the canon “Happy New Year!” written on 31 December 1819 for Baron Pasqualati, Beethoven’s landlord in Vienna for well over ten years. Let us join Beethoven and wish all our readers a Happy 2022.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: “Glück zum neuen Jahr!” WoO 165 (Cantus Novus Wien, choir; Thomas Holmes, cond.)