Simone Menezes © Daniela Cerasoli

Italian-Brazilian conductor Simone Menezes faced the problem of being a female conductor in the classical world head on. She noted that her male contemporaries were getting jobs and she wasn’t. She seemed to fall out of the way people think of conductors – male good, female invisible. Knowing that the problem wasn’t her work, but the perception of female conductors, she started creating her own projects to advance her ideas.

One of the latest projects she’s been performing is about the Amazon Rainforest. She started with Villa-Lobos’ last major orchestral work, his symphonic poem Floresta do Amazonas (Forest of the Amazon), a 23-part, 80-minute cantata for chorus and orchestra that presents the Amazon as a Brazilian entity. From the use of indigenous Amazonian language in the choral sections to Villa-Lobos’ own sweeping harmonies and rhythms that convey Brazil to the world, the work embodies all of Villa-Lobos’ profound love for his country. Villa-Lobos had been commissioned to write the music for the 1959 film Green Mansions, but, in the end, MGM used very little of his music, and he took back his music and created his cantata.

© Daniela Cerasoli

For Amazônia, Menezes created a multi-media event that encompasses an outsider’s view of the Amazon (Philip Glass’ ‘Metamorphosis 1’ from Aguas da Amazonia), Villa-Lobos’ 1941 Bachianas brasileiras No. 4, which brings together the suite design of Bach, a melody from The Musical Offering, and Villa-Lobos’ own melding of melody and birdsong, and an arrangement of his Floresta do Amazonas. The original Floresta do Amazonas was edited down to a 11-part, 45-minute suite, and paired with black and white images taken in the Amazon by Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado.

Philip Glass: Aguas da Amazonia: No. 10. Metamorphosis I (Uatkti)

Heitor Villa-Lobos: Bachianas brasileiras No. 4 for Orchestra: IV. Danza: Miudinho (Nashville Symphony Orchestra; Kenneth Schermerhorn, cond.)

The rain is so intense in Serra do Divisor National Park that it looks like an atomic mushroom cloud. State of Acre, 2016 © Sebastião Salgado

Like many of Menezes projects, this one is intended to make her audience think, discuss, and change their ideas. She worked extensively with the photographer to match images to musical phrases. Salgado’s images capture the living forest and the people who live in it, just a Villa-Lobos’ music captures his vision of the forest.

When Menezes first started broaching projects with Brazilian themes in Europe, she was often dismissed with the comment ‘Brazilian music? That’s for summer programming’, an idea that she found laughable. Brazil is more than just samba and bossa nova, it’s not just light music and dancing, it’s music with a serious message. Art has to speak to the heart bypassing the brain’s desire to add politics into the mix. This is part of her dream: to create meaningful projects that can change the world.

An upcoming project is Metanoia, to debut later this year, looks at music as the balance point between the mind, the soul, and the spirit. Now, we seek entertainment without knowledge (hands up, everyone who did a Netflix binge during the global lockdown). Menezes seeks to make classical music the means by which we come to that balance point. She counters the frequent declaration that classical music is elitist by pointing out how effective projects such as El Sistema have been in reaching children in the favelas of Rio di Janeiro and other poor regions of South America and bringing them to the classics.

We talked about the change over the past 20 years in the number of women conductors who are coming to the fore. She noted that many earlier women conductors, such as Marin Alsop, also had to take their careers in their own hands and devise project that they could present to the world. Amazônia is Menezes’ and Metanoia will be another.

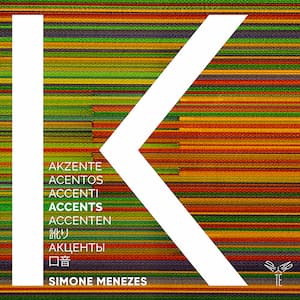

Simone Menezes’ latest recording Accents

We also discussed her recent recording, Accents, with her ensemble, K, of music from an international collection of composers: Borodin, Debussy, Copland, Villa-Lobos, and French composer Sophie Lacaza (b. 1963). Menezes has been examining national styles and if it’s possible to play classical music without an accent, i.e., to play Copland understanding the musical styles of America, or to play Borodin understanding the ethnographic studies he did to create his work. It’s one of her goals to make classical music borderless: playing not just the notes but also the cultural concepts behind those notes.

One of the interesting elements of Menezes’ recording was the small ensemble that she created it with. K is made up of 12 players, one per part for strings, piano, accordion, and woodwinds. There are two first violinists, but no brass players or percussionists. She said that large ensembles made it difficult to hear the details, whereas in small ensembles, it’s all about the details. Listening to a minimalize Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances is a different experience. We’re used to hearing this played as part of an opera with a large orchestra – now listen to the different internal lines you’ve never heard before.

Alexander Porfir’yevich Borodin: Prince Igor (Knyaz Igor), Act II: Polovtsian Dances (arr. V. Paulet for ensemble) (K; Simone Menezes, cond.)

Perhaps the idea that best summarizes Menezes ideas is listed in the Accents album. The K ensemble stands for: Klassic, Kosmopolitan, Kontemporary, Kreative, and Konnected and that is a wonderful summary of Menezes’ work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter