Henryk Górecki

In spite of the term, these composers disliked being grouped together and while their music shares common traits and a similar aesthetic (simple melodies and radically pared-down compositional materials), they are not a close-knit community of composers and each has a distinctive compositional voice. However, the three composers below have one particular aspect of their compositional lives in common – they were all exposed to and explored the avant-garde and atonality before finding a new, purer expression for their musical output.

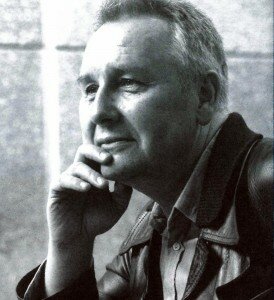

Henryk Górecki

Symphony No. 3

Largely unknown outside Poland until the 1980s, Henryk Górecki’s fame came late with the release in the early 1990s of his Third Symphony, the ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’, a work of ‘sacred minimalism’ whose dominant themes are motherhood and separation through war. Written to commemorate victims of the Holocaust, the work is regarded as a reflection on that dreadful rupture in twentieth-century history and became an overnight success for this previously little-known Polish composer.

“Perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music […] somehow I hit the right note, something they were missing. Something somewhere had been lost to them. I feel that I instinctively knew what they needed.”

The music has an expressive immediacy, straightforward in its construction and attractively consonant harmonies. Górecki’s earlier music can be acerbically avant-garde, drawing on the uncompromisingly dissonant works of Webern, Stockhausen, Boulez and Nono. Sometimes violent and colourful, he takes a big idea and then subjects it to discordant, clashing forces, often incorporating the folk music and traditions of the Tatra region of Poland, an area of the country whose music and culture had also influenced fellow countryman Karol Szymanowski. But the simple monumental style inspired by religious music, which makes the Third Symphony so appealing, is already present in Górecki’s earlier works. The String Quartet No. 1, for example, written for the Kronos Quartet, takes a Renaissance part-song as its raw material, which is transformed into a peaceful chorale and a folksy dance; while his choral music has a haunting meditative quality, connecting him with other composers of “sacred minimalism” such as Arvo Pärt and John Tavener.

Energy and contemplation are the two key features of Górecki’s music, creating an immediate and powerful impact on the listener.

Totus Tuus

Arvo Pärt © K. Kikkas

“The complex and many faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity”

Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten for Strings and Bells

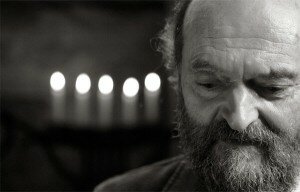

In the 1960s, although largely cut off from contemporary Western classical music, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) experimented with the then fashionable musical genres of serialism, collage, neo-classicism and aggressive dissonance – styles which confirmed his modernist credentials, but set him at odds with the Soviet authorities. Frustrated with the dry “children’s games” of the avant-garde, and, as a reaction to this and in an attempt to find his own compositional style, he went into self-imposed creative exile, during which he explored the traditions, both musical and cultural, he was most drawn to: Gregorian chant, harmonic simplicity, and his Russian Orthodox faith. What emerged was a distinctive and unique compositional voice: the music of “little bells”, or “tintinnabuli”, heard for the first time in his piano miniature Für Alina. This piece set the seed from which his most famous music grew – Spiegel im Spiegel, Fratres, Summa, and Tabula Rasa.

It’s easy to dismiss Pärt’s music as simplistic, sentimental and clichéd, but his music’s power lies in both its absolute simplicity and the austere rigour applied to its construction. And here Pärt was harking back to his explorations in serialism, devising his own strict rules to control the movement of harmonic voices within the music. As a result, his music sounds both archaic and avant-garde, capturing the ancient sounds and Gregorian chants of monasteries in a way that is strikingly modern and minimalist. The music has a spare, profound and meditative expressivity, from hauntingly simple pieces for solo piano to elaborately layered works for full orchestra – all of it atmospheric and compelling.

Fratres for Cello and Piano

John Tavener

“I see music as ‘a window of sound’ on to the divine world.”

The Lamb

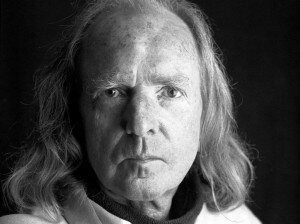

In common with other composers of ‘holy minimalism’, the music of John Tavener (1944-2013) is largely informed by his faith (he was received into the Russian Orthodox Church in 1977) and theology and liturgical traditions are a major influence on his work.

Like Arvo Pärt and Henryk Górecki, Tavener’s early musical training was in the fashionable white-hot furnace of the avant-garde in the 1960s. While at London’s Royal Academy of Music, his studies with Lennox Berkeley led to exposure to the music of Boulez, Ligeti and Messiaen; at the same time, he grew friendly with The Beatles and John Lennon invited Tavener to record his dizzying psychedelic musical melange ‘The Whale’ on the Beatles’ Apple label which brought impressive early recognition.

But Tavener was dissatisfied with the avant-garde and sought a purer, more uncluttered style. His journey into Eastern Christianity, and from there to Sufism and Hinduism, led to the creation of his most significant works, including The Lamb, Resurrection, The Protecting Veil, Song for Athene and The Veil of The Temple. In these works, liturgical chant is layered with clean harmonies and eastern rhythms, creating profound music of haunting spirituality whose roots lie in the ancient chants of the Orthodox Church but which is also startlingly contemporary.

Song for Athene

Tavener’s music has a mesmeric simplicity and ethereal spaciousness in which the smallest gestures have great significance (The Lamb, for example, comprises just seven notes, ingeniously crafted into a work of intoxicating beauty). It is music which demands attentive listening: as each simple melodic line opens up, one has the sense of something far greater stretching into the infinite, and of time suspended, blissful and meditative.