Credit: http://www.orthodoxartsjournal.org/

The piece has earned the status of “iconic”, largely due to the fact that it has been much used in film and television soundtracks, as well as in ballet and theatre productions; it is hard to credit now that Pärt’s music was relatively unknown in the west until the 1990s. The work’s recurring motifs – rising crotchet second-inversion broken chords in the right hand of the piano and sustained notes in the violin (or other instrument) which slowly ascend and descend – are instantly recognisable.

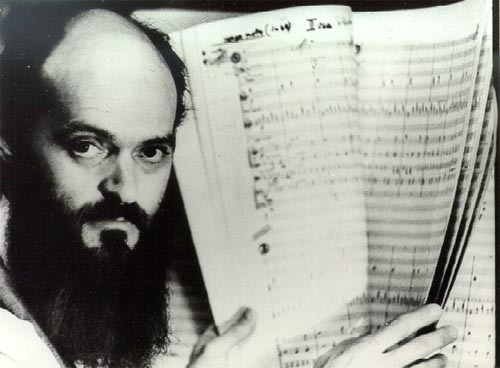

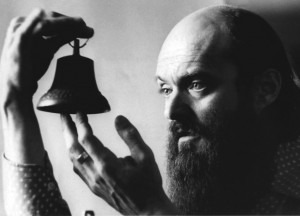

In the 1960s, although largely cut off from western contemporary classical music, Pärt experimented with serialism, collage, neo-classicism and aggressive dissonance, styles which cemented his modernist credentials, but set him at odds with the Estonian Soviet authorities. However, he was frustrated with the dry “children’s games” of the avant-garde, and, as a reaction to this and in an attempt to find his own compositional style, he went into a self-imposed creative exile, during which he explored the traditions, both musical and cultural, he was most drawn to: Gregorian chant, harmonic simplicity, and his Russian Orthodox faith. What emerged was a distinctive and unique compositional voice: the music of “little bells”, or “tintinnabuli”, heard for the first time in his piano miniature Für Alina. This piece set the seed from which his most famous music grew, including Spiegel im Spiegel, Fratres, Summa, and Tabula Rosa.

Spiegel im Spiegel

It is easy to dismiss Pärt’s music as simplistic, sentimental and clichéd, but the music’s power lies in both its absolute simplicity and the austere rigour applied to its construction. And here Pärt was harking back to his adventures in serialism, devising strict rules to control how the harmonic voices move within the music. As a result, his music sounds both ancient and avant-garde, while the new tonalities of the “little bells” and the simple harmonic progressions give the music a spare, profound and meditative expressivity.

The German title Spiegel im Spiegel means both “mirror in the mirror” as well as “mirrors in the mirror”, referring to the infinity of images produced by parallel plane mirrors. In the music, this mirroring is achieved through the fragments in the piano, which are endlessly repeated with small variations, as if reflected back and forth. These repeating fragments also invoke, in tintinnabuli style, the twilight first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 27 no. 2, the ‘Moonlight’, with its peaceful recurring triplets. The piano part also reaffirms the melody notes of the violin line with parallel thirds and octaves, and further voices unfold from the core note, A. F major, the key in which the piece is written, remains the underlying and omnipresent tonality throughout.

The piano part carries the tintinnabular voice with its repeating broken chords and low, sustained Fs in the bass. The texture is coloured throughout by high, bell-like (“tintinnabular”) recurring sounds in the upper registers. The violin line is based on a slow ascending melodic line, beginning with a G-A two-note scale, which alternately ascends then descends to A by step. With each subsequent ascent and descent, a note is added to the line, a process which could go on indefinitely (the “mirror in mirror” again). It is this continuity and constant inversion of the violin line, combined with the piano, that creates the sense of perfect tranquility. There is no drama or ambiguity here because we know the music will always return to the “home” tonality of A, and the emotional content comes from introspective atmosphere created by the simplicity and pure sonorities of the music.