Pianist and composer Clara Schumann was one of the most influential musicians of her generation. One of the ways we can measure that influence is by looking at the many works that were dedicated to her by her colleagues.

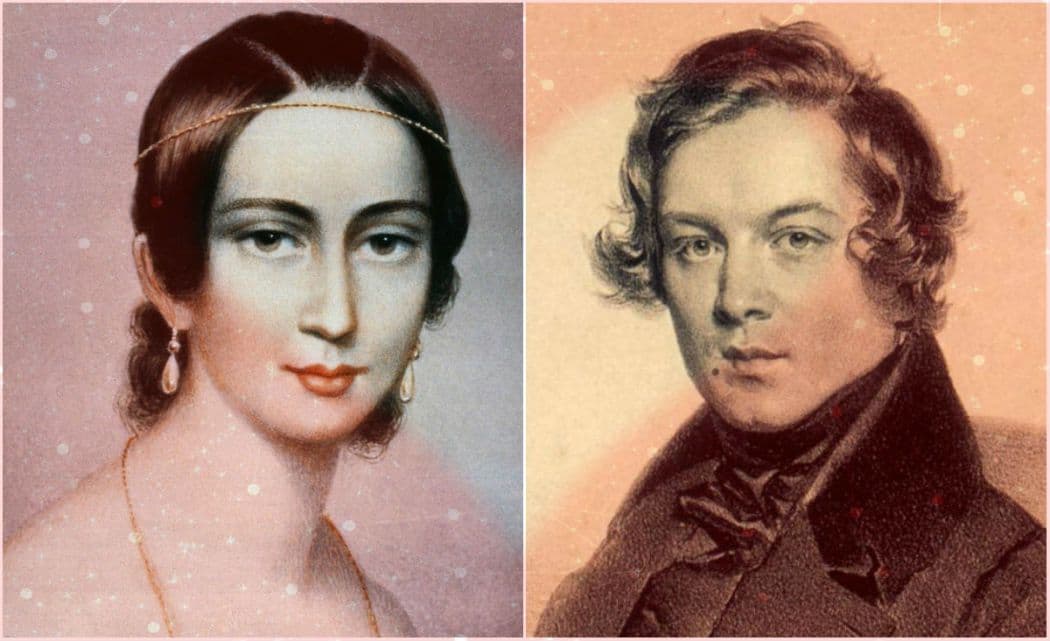

Clara Schumann

Going chronologically, here are the fascinating stories behind pieces that were dedicated to Clara Schumann:

Robert Schumann: Symphony No.4, Op.120 (Original Version) (1841)

Robert and Clara Schumann

After a rocky courtship sullied by the interference of Clara’s father, Robert and Clara Schumann were married in September 1840, the day before her twenty-first birthday. The following year, Robert wrote his fourth symphony and dedicated it to Clara. A decade later, he revised the score and dedicated that version to their mutual friend, violinist Joseph Joachim. This later one is the version that we know today.

Later in life, Clara got into a famous argument with Johannes Brahms over this symphony. She preferred the later version, while, ironically, Brahms preferred the earlier one that had been dedicated to her!

The two even issued dueling versions of the score. In 1882, Clara authorized the publication of the later version, going so far as to claim that the earlier version had not been fully orchestrated. Then in 1892, Brahms published that earlier version, over Clara’s objections. Luckily nowadays it’s easy to hear and enjoy both.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte, Op.62 (1844)

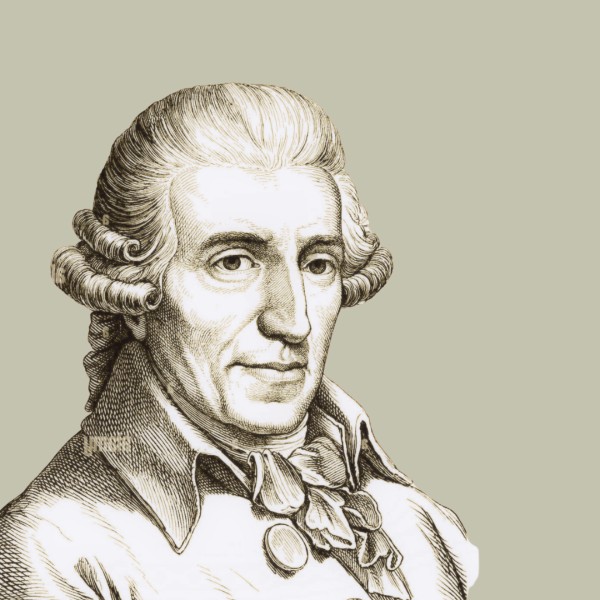

Felix Mendelssohn © U.S. Public Domain

In response to the Romantic Era’s obsession with songs and short lyrical instrumental pieces, Mendelssohn wrote no fewer than eight volumes of Lieder ohne Worte (“Songs Without Words”). He dedicated his fifth book of these songs, which became his op. 62, to Clara Schumann.

The Op. 62 contains six of Mendelssohn’s most delightful Songs Without Words. The wistful first is dreamy and melancholic. The second is a jaunty tune in 12/8 time. The third is a bold, dramatic funeral march. The fourth is a simple and charming country dance just under two minutes in length. The fifth is a romantic Venetian boat song. The sixth is one of the most famous Song Without Words of all: the Spring Song, which has been heard on countless classical music compilation discs.

Felix Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 5, Op. 62 (Daniel Barenboim, piano)

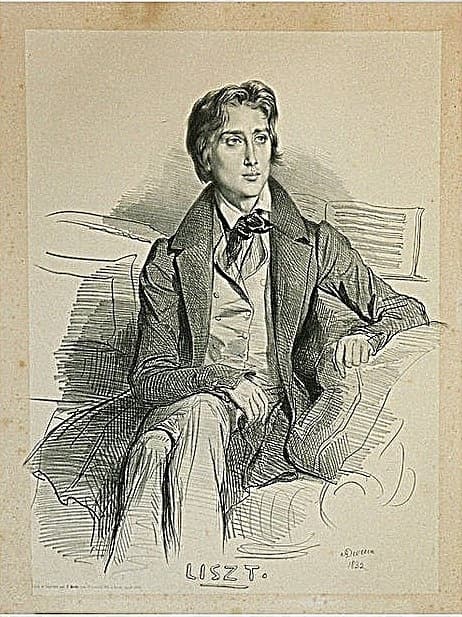

Franz Liszt: Grandes études de Paganini, S.141 (1851)

Portrait of Franz Liszt, 1832

Clara Schumann had famously mixed feelings about Liszt’s brand of showmanship. She deeply respected his virtuosity, but her personal aesthetic tastes were very different from his, and much more understated. She was also intimidated: “Ever since I heard and saw Liszt’s bravura, I feel like a beginner,” she confessed to Robert in a letter in 1838.

It’s amusing, then, that Liszt dedicated his famous Grandes études de Paganini, which are ultra-virtuosic piano transcriptions of ultra-virtuosic violin pieces, to her: true evidence of the high regard that he held her in. Clara may have fretted about her technical abilities in comparison to Liszt’s, but he clearly felt she could hold her own!

This set of etudes includes the famous La Campanella transcription for piano, whose popularity has arguably outpaced Paganini’s original.

Franz Liszt: Grandes Etudes de Paganini, S141/R3b (Daniil Trifonov, piano)

Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op.9 (1854)

August Weger: Bildnis von J. Brahms, 1960 (Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky)

In the autumn of 1853, Johannes Brahms came to visit the Schumanns, and the three quickly became fast friends. Soon Brahms fell deeply in love with Clara. But tragedy struck in February 1854, when Robert had a mental health crisis and attempted suicide. He asked to be brought to an asylum for his own safety and the safety of his family.

Clara was absolutely distraught, not to mention pregnant with her and Robert’s last child. During this time, Brahms stayed near to provide support. One of the ways he did so was through music, whether by playing piano for Clara, playing duets with her, or just appreciatively listening to her magnificent playing. During one of these musical exchanges, she played for him her “Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann,” which she had composed the year before. As a gift, Brahms took the theme and wrote his own variations. It’s one of the most quietly devastating pieces in his entire creative output and a world away from Liszt’s brash Paganini etudes.

Woldemar Bargiel: 3 Fantasiestücke, Op.9 (1855)

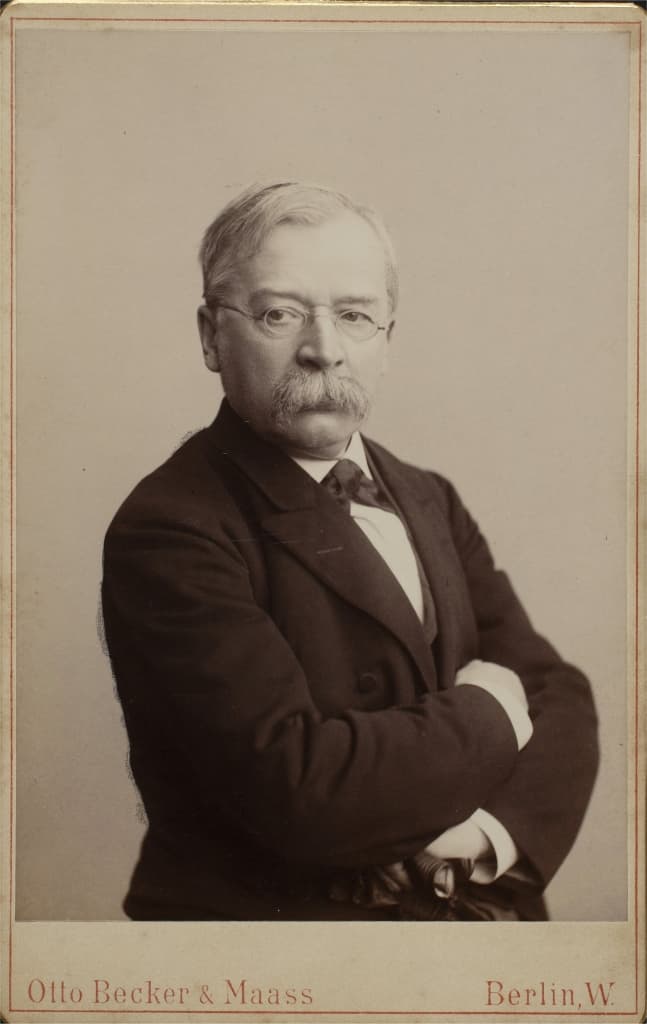

Woldemar Bargiel in 1885 © Wikipedia

Clara’s father, piano teacher, and entrepreneur Friedrich Wieck, was famously demanding and abusive. In 1816 he married Clara’s mother, a well-known singer named Mariane Tromlitz. Clara was born three years later. Not long afterward, the Wieck marriage fell apart. Mariane started having an affair with a friend of Friedrich’s named Adolph Bargiel. She and Wieck were divorced in 1824, and she married Bargiel soon after.

In 1828 Mariane Bargiel gave birth to Woldemar Bargiel. Despite the estrangement of their parents, Clara and Woldemar were deeply devoted half-siblings. Following in the footsteps of his family, Woldemar became a teacher and composer. In 1855 he dedicated the 3 Fantasiestücke (“3 Fantasy Pieces”) for solo piano to his famous half-sister.

Johannes Brahms: 6 Klavierstücke, Op.118 (1893)

Clara Schumann and Brahms © londonsymphonia.ca

Toward the end of his and Clara Schumann’s intertwined lives, Johannes Brahms began writing this collection of small, poignant pieces for piano, consisting of four intermezzos, one ballade, and a romanze. The bittersweet second intermezzo in A major is one of Brahms’s most famous pieces.

Johannes Brahms: 6 Piano Pieces, Op. 118 (Paul Lewis, piano)

In his Brahms biography, Jan Swafford describes a late-in-life meeting between Clara and Johannes:

Next morning Eugenie [Clara’s daughter] heard the sound of the piano from the music room. It was Bach, followed by two pieces from Brahms’s Opus 118, music he had written to sustain Clara, and which she loved. When the music stopped Eugenie went into the room and found her mother at her writing table, her cheeks flushed and eyes shining, and Brahms sitting opposite her with tears in his eyes. Gently he said to Eugenie, “Your mother has been playing most beautifully for me.”

After a moment he asked Eugenie to get a particular volume of Beethoven Sonatas from the shelf. In it, he pointed out a place where Clara had long ago corrected a mistake that had appeared in every edition. “No other musician has an ear like that,” he said.

They bid farewell to each other, and Brahms caught his train. Clara died not long afterward, and Brahms less than a year after her. It is fitting that these beautiful pieces were the last music they shared together.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

The last part quoting Brahms is incredibly touching. To hear the second intermezzo afterwards is cause for a meldown of emotion and sadness.