Today, Johannes Brahms is considered a towering figure in 19th-century music, and his symphonies are a cornerstone of the classical repertoire. However, his music enjoyed a rather complex and evolving reception, especially in the Anglo-American world. In Britain and the United States, his works initially met with a mixture of admiration and resistance, reflecting both the cultural tastes of the time and the challenges posed by his dense, intellectually rigorous compositional style.

The young Johannes Brahms

During the late Victorian era, British audiences were accustomed to the lighter, more immediately accessible works of composers like Mendelssohn or the popular operatic fare of the day. Brahms’ music, with its intricate structures, rich orchestration, and introspective depth, demanded a level of engagement that some found daunting.

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 “Un poco sostenuto—Allegro”

Brahms in the United States

In the United States, Brahms’ reception followed a similar trajectory, though it was shaped by the nation’s emerging musical identity. His music arrived as part of a broader wave of German musical immigration, and while some conductors championed his symphonies, chamber music, and choral works, a good many listeners and critics found his output overly cerebral.

Some embraced Brahms for his emotional restraint and architectural precision, while others asserted that it lacked the melodic immediacy of Italian opera or the dramatic flair of Wagner. In his “Lexicon of Musical Invective”, Nicolas Slonimsky compiled critical assaults on a number of composers. As such, let’s take a look at dissonance aimed at the symphonies of Johannes Brahms.

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 “Andante sostenuto”

Scoundrel Brahms

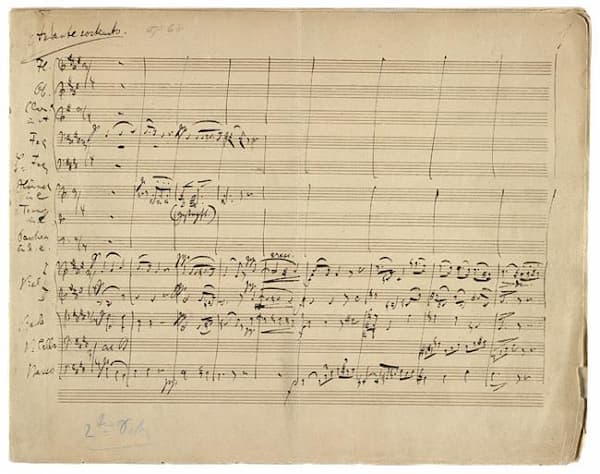

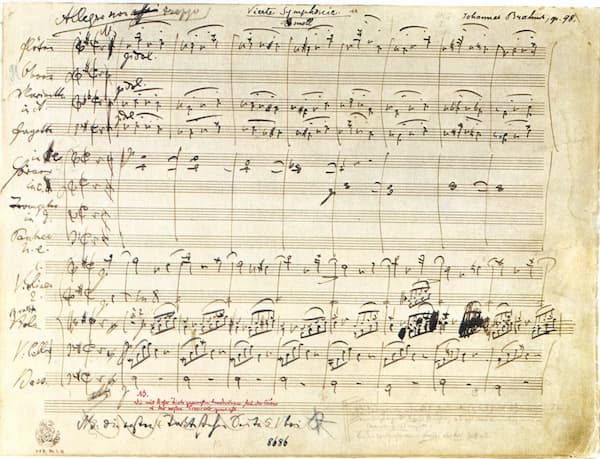

Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 autograph

In his Diary, in an entry on 9 October 1886, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky spitefully writes, “I played over the music of that scoundrel Brahms. What a giftless bastard! It annoys me that this self-inflated mediocrity is hailed as a genius. Why, in comparison with him, Raff is a giant, not to speak of Rubinstein, who is, after all, a live and important human being, while Brahms is chaotic and absolutely empty dried-up stuff.”

While this colourful rant reveals more about Tchaikovsky’s temperament and biases, it nevertheless mentions some criticisms habitually aimed at Brahms. Foremost among them was the charge that Brahms’ music was disorganized and lacked vitality or substance. In essence, Tchaikovsky saw no emotional depth or creative spark in the music of Brahms.

Tchaikovsky’s criticism is mirrored in a review published in the New York Post on 8 November 1880. A critic writes, “The principal work of the evening was Brahms’s Symphony in C minor. We think a better choice might have been made for an opening concert… It is poor in ideas, and the few that are there lack originality. They do not warm us; they do not speak to our hearts’ emotions. Everything is measured, cold and of aristocratic reserve.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 “Un poco allegretto e grazioso”

Lack of Melody

A number of critics claiming that Brahms lacked melody frequently focused on the perceived complexity and intellectual rigour of his music. Composer and critic Hugo Wolf famously wrote in the 1880s that Brahms’ music “was sterile and lacked the sensuous melodic line found in Wagner.” Brahms’ focus on counterpoint and structural development, it was argued, came at the expense of spontaneous, flowing melodies.

As W. F. Apthorp writes in the Boston Courier on 20 January 1878, “The Brahms C minor Symphony sounds for the most part morbid, strained and unnatural; much of it even ugly. Melody has become, by this time, a pretty vague term, but when it comes to an oboe and a clarinet making absolute speeches at each other the listener’s mind is at so great trouble to remember what the first has said, that it is impossible to appreciate whether the reply of the second is pertinent or not.”

And a Boston critic, writing only a couple of days hastily remarked, “The First Symphony of Brahms seemed to us as hard and as uninspired as upon its former hearing. It is mathematical music evolved with difficulty from an unimaginative brain… All that we have heard and seen from Brahms’s pen abounds in headwork without a glimmer of soul.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 “Adagio-Allegro non troppo”

Irritant and Restless Discords

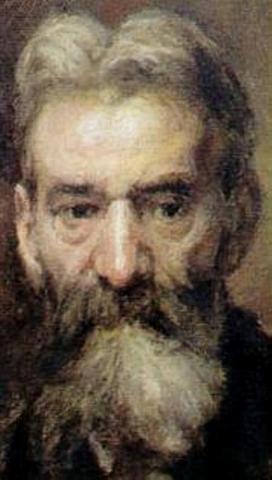

Johannes Brahms, c. 1885

Brahms’ C-minor symphony was frequently taken to task for a reiteration of mere fragmentary ideas, “which makes it simply tiresome.” The Boston Evening Transcript reports on 16 November 1885, “Lovers of Brahms were much disturbed by large numbers of people leaving the hall between the movements of the C minor Symphony.”

For a number of listeners, the first symphony of Brahms “seemed to strive after the unattainable; it is full of irritant and restless discords; it has strange, climbing, grasping phrases which seem to be trying to drag down something which still glides upward from their reach; its pastoral motifs often break away in suggestion of storm and confusion; and strings are frequently urged to the very top of their compass, and at times, it whirls everything away in a rhythmic chaos.”

The conception that Brahms was unable to compose melodiously resurfaced in criticisms of his 2nd Symphony. A critic in Boston writes, “It would appear as though Brahms might afford occasionally to put a little more melody into his work, just a little now and then for a change. His Second Symphony gave the impression that the composer was either endeavouring all the while to get as near as possible to harmonic sounds without reaching them, or that he was unable to find any whatever.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73 “Allegro non troppo”

Brain Music

It was frequently suggested that the music of Brahms prioritised intellectual structure over emotional immediacy. And there is certainly some truth to that perception, as Brahms, the master craftsman, was obsessed with form, counterpoint, and musical logic. His symphonies are packed with dense and interlocking ideas that give the impression of meticulously constructed musical blueprints.

The critic for the Boston Courier reports on 11 January 1879, “I have studied the second movement of the Second Symphony of Brahms with the greatest attention. Well! I have not the faintest idea what the composer means. It seems as if it were only by the greatest effort that Brahms could firmly fix his own conceptions. Whatever he writes, he seems to have to force music out of his brain as if by hydraulic pressure. It would take a year to really fathom the Second Symphony, and a year of severe intellectual work, too.”

And Dwight’s Journal of Music adds a couple of months later, “We do not find ourselves at all alone in saying that the Second Symphony of Brahms does not improve upon acquaintance. There is a certain feebleness, a sugar-and-water character, in the subject matter of the themes; and when it comes to the working up, it is done with an unstinted use of contrapuntal means.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73 “Allegro non troppo” (Philharmonia Cassovia; Otakar Trhlik, cond.)

Distracting Headache

The review continues to call out “obscure and unsatisfactory periods,” before returning to criticism of Brahms’ counterpoint. “This super-refined contrapuntal distillment has produced nothing better than a bad quality of spirit, which shows its effects upon the brain in an uncomfortable and distracting headache. It still refuses to reveal its meaning, and leaves us with the sense of having hastened to something ugly and ungenial.”

The 2nd Symphony was called fragmentary and disjointed, with the rhythm and the tempos continually changing without warning and apparently without reason. For many, it did not arouse much enthusiasm. As a critic sarcastically remarked, “what work of Brahms ever did?” And he added, “of course, it is an exceedingly erudite work, so to speak, containing details which betray an honest and profound musical thinker; but it lacks grand, sweeping ideas, and is deficient in sensuous charm.”

Edgar Stillman Kelly of the San Francisco Examiner writes on 9 May 1894, “After the weary, dreary hours spent in listening to the works of Brahms, I am lost in wonder at the amount of devotion accorded him and the floods of enthusiasm with which he is overwhelmed. He gives us nothing in the way of beautiful themes, lovely harmonies or refreshing modulations.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73 “Allegretto grazioso” (South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden and Freiburg; Michael Gielen, cond.)

Emotional Impotence

George Bernard Shaw

Brahms’ music was described as a noisy, reverberating void. J. F. Runiciman writes in 1900, “I by no means wish to call Brahms an idiot; he was something considerably more than that; but if a boy or a man, who is an idiot in all other respects, can sometimes attain to an astonishing mastery of figures, surely it is not unfair to suppose that Brahms may have had this wonderful technical musical talent without any special brain power in other respects. Only once or twice was Brahms really expressive of an original emotion, and that emotion was the feeling of despondency, grief, melancholy, which was aroused in him by a sense of his own emotional impotence.”

George Bernard Shaw went even further in his assessment of 1893. “To me, it seems quite obvious that the real Brahms is nothing more than a sentimental voluptuary. He is the most wanton of composers. Only his wantonness is not vicious; it is that of a great baby, rather tiresomely addicted to dressing himself up as Handel or Beethoven and making a prolonged and intolerable noise.”

And Philip Hale added, “The weak despair of Brahms and the snivelling pessimism of some of his absolute music may be attributed justly to his constitutional defect.” And Edwar Lome writes in London in 1922, “Art is long and Life is short; here is evidently the explanation of a Brahms symphony.”

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 73 “Allegro con spirito” (London Philharmonic Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

Political Dimension

Johannes Brahms’ Symphony No. 4

Friedrich Nietzsche, deeply engaged with music through his early admiration and later disillusionment with Richard Wagner, saw Brahms as a pillar of the German musical tradition during the rise of the Bismarck Reich. He called Brahms “the musician of a disappointed people,” linking his music to a middle-class sensibility that he felt stifled genuine creativity and vitality. As he writes, “the sympathy that Brahms undeniably inspires now and then, was for a long time a puzzle to me, until I finally, almost by accident, realised that he impresses one definite type of people. He has the melancholy of impotence; he creates not out of abundance; he yearns after abundance.”

George Bernard Shaw, an ardent champion of Richard Wagner, viewed Brahms as a conservative throwback, a composer clinging to outdated forms. Shaw saw the music of Brahms as “a string of third-rate musical platitudes,” and as a darling of the establishment. Essentially, Shaw viewed Brahms within a broader disdain for Victorian complacency. He saw Brahms’ popularity as a symptom of a society unwilling to embrace the radical and the new.

As he writes, “Brahms takes an essentially commonplace theme; gives it a strange air by dressing it in the most elaborate and far-fetched harmonies; keeps his countenance severely; and finds that a good many wise-acres are ready to guarantee him as deep as Wagner, and the true heir of Beethoven. . . Strip off the euphuism from these symphonies and you will find a string of incomplete dance and ballad tunes following one another with no more organic coherence than the succession of passing images reflected in a shop window in Piccadilly during any twenty minutes in the day.”

Johannes Brahms and his symphonies have long stood as lightning rods for criticism, drawing ire for philosophical, aesthetic, and political reasons. However, beneath these criticisms lies a paradox. The very qualities they scorned, specifically his meticulous craftsmanship, his restless discord, and his striving ambition, also secured his enduring stature. His symphonies, far from mere relics, continue to provoke and inspire, their turbulent depths revealing a composer who, whether loved or loathed, refused to be ignored.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

These attacks on Brahms can only emanate from ignoramuses, the deaf, or as in the case of Tchaikovsky, envy. Those of us without prejudices have to laugh because we are engulfed with Brahms’ technical and aesthetic genius, his dedication to form and structure, his elaboration on simple musical themes, and in the end the overwhelming intense joy of hearing musical genius at its best. No one (except possibly Beethoven) exceeds Brahms in all aspects. LOL are due those who were and are intellectually and aesthetically incapable of enjoying one of the greatest artistic expressions ever shown in music. Brahms is my “desert island” composer, keeping me alive.