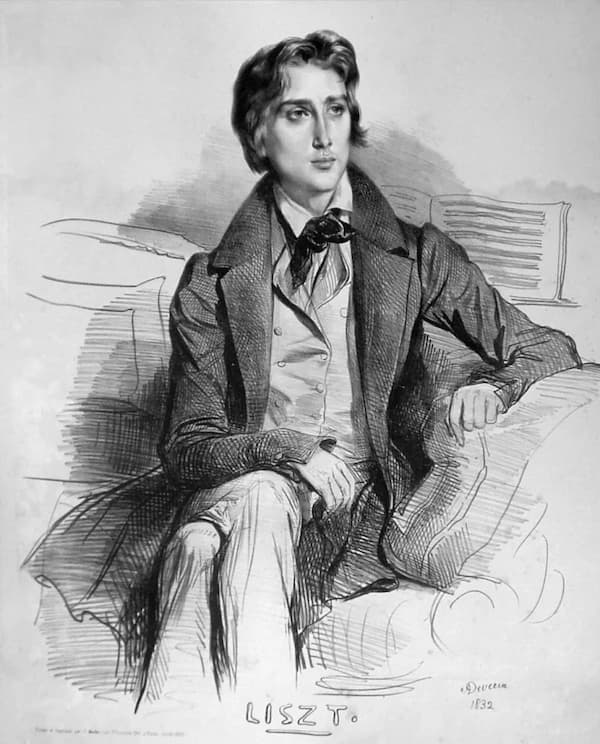

The Wiener Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung reports on 7 December 1822, “on 1st December a very talented boy by the name of Liszt, coming here from Pressburg, gave a concert in the town grand concert-hall, and through his playing and his remarkable facility aroused general wonder. He received great and rousing applause.” Famously, of course, Liszt also met up with Beethoven, courtesy of his teacher Carl Czerny, himself a student of Beethoven.

Franz Liszt

In his autobiography, Liszt describes this meeting in much detail and how he impressed Beethoven with a transposition of a Bach fugue. After hearing him play Beethoven’s own concerto, Beethoven praised him, saying, “he is destined to bring joy to many people.” Liszt would describe this event as the “proudest moment” in his life. Details of the encounter, none withstanding, it certainly marked the beginning of an enormous artistic journey.

Only a couple of years later, Liszt began composing the Etude en douze exercices, which was initially published in 1826 as Opus 6, and promised 48 exercises but containing only twelve. These studies formed the foundation for later works, including the Vingt-quatre grandes études (1837), dedicated to Carl Czerny, and the famous Etudes d’exécution transcendante (1851). These versions represent Liszt’s evolving technical and artistic vision, from a young composer to a mature virtuoso, all aimed at expanding piano technique. In this final episode, let us conclude our exploration of the technical and artistic evolution of Liszt’s transcendental temptations.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 9 in A-flat Major “Allegro Grazioso” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

3 Etudes in A-flat Major

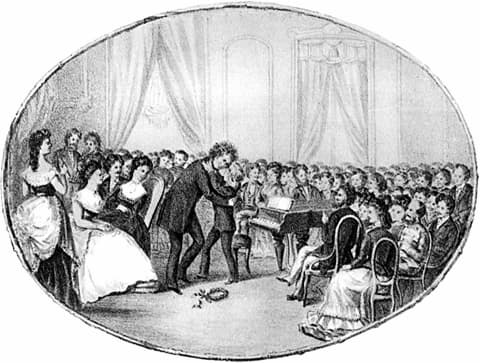

Beethoven embraces Liszt

The A-flat Major etude from 1826 is essentially a technical study with faint hints of lyricism. However, it lacks the dramatic emotional contrast found in the later version. The harmonic language is fairly standard, with predictable modulations and progressions, and the piece offers an early glimpse into Liszt’s ability to combine technical challenges with lyrical expression.

Nevertheless, the 1826 prototype remains the most astonishing piece of the juvenile set. The themes and harmonies were taken over almost unchanged in 1837, “and the filigree decoration sets off their beauty in the subtlest way.” While the material of the earlier etude is taken over unchanged, the 1837 version reflects more advanced piano techniques, showing a greater sophistication in both technical demands and music expression. It requires greater finger agility and dynamic control and introduces more complex hand crossing and rapid passages.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 9 in A-flat Major “Andantino” (1837) (Wenbin Jin, piano)

In the final version, Liszt titled the A-flat Major etude “Ricordanza” (Remembrance). As in all other versions, it has a lovely character, sounding elegiac, lyrical, and delicate. Busoni likened this etude to “a bundle of faded love letters from a somewhat old-fashioned world of sentiment.” Essentially, it is composed in the style of a berceuse, sounding a melody of charm, gentleness, and elegance.

It is the longest piece in the cycle, lasting almost ten minutes. The primary melody is repeated several times throughout in a very relaxed tempo. Nevertheless, it is not an easy piece to play. The melody begins in the left hand and is developed with multiple variations, each containing different technical aspects. These variations are constantly changing and become thicker and more complex over the course of the piece. It all builds to a climax after a delicate cadenza, and this etude dissolves into a mist of ethereal improvisation.

3 Etudes in F minor

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 9 “Ricordanza”

The early version of the F-minor etude is a vivid example of Liszt’s technical skill and compositional ingenuity during his formative years. It certainly is technically challenging as the hands are required to coordinate rapid passagework and a constant stream of arpeggios. In these passages we glimpse Liszt’s increasing interest in the piano’s potential for both virtuosity and expressive agility.

There is a sense of momentum throughout, with frequent shifts between light and more delicate sections and those that demand power and speed. The main theme recurs, developed as brief variations, though the overall design remains relatively conventional. We are still missing some of the more radical structural innovations that will characterise his later compositions. However, its lively character and spirited rhythms make it an exhilarating piece to hear and perform.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 10 in F minor “Moderato” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

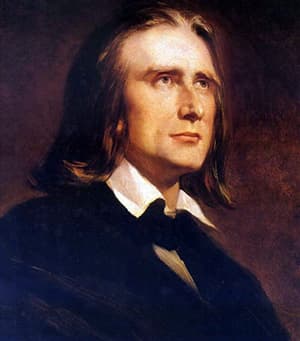

Franz Liszt

In the 1830s, Liszt was under the spell of Paganini. The level of astonishment provoked by the Italian violinist is summarised in one of Liszt’s letters. “For a whole fortnight, my mind and my fingers have been working like two lost souls… In addition, I practice four to five hours a day of exercises (thirds, sixths, octaves, tremolos, repetition of notes, cadenzas, etc.) Ah! Provided I don’t go mad, you will find in me an artist!”

This infatuation is once again seen in the 1837 version, as Liszt develops a much more aggressive and fiery style, evident in the technical challenges he imposes on the performers. These include rapid passagework requiring agility and smoothness, large intervallic leaps that demand precision in hand coordination, and contrasting themes that necessitate hand independence. Effective pedalling is crucial for clarity, while dynamic control, speed, and stamina are essential. Additionally, intricate fingering and articulation are needed to maintain clarity and precision, ensuring each note in rapid passages is distinct, and the overall texture remains cohesive.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 10 in F minor “Presto molto agitato” (1837) (Wenbin Jin, piano)

For pianist Leslie Howard, the Tenth Study in F minor, which carries the title “Appassionata,” is the finest of the 1851 set. Although more imposing in the 1837 version, Liszt’s later solution for the layout of the opening material produces a more restless effect by eliminating the demand for playing melody notes with the left hand in amongst double sixths in the right. The 1837 version also had a much longer coda, which abruptly changes the meter and becomes ferocious.

This etude is popular in concerts and competitions for its mix of beautiful melodies and technical brilliance. The left hand is the more challenging part, handling wide, fast arpeggios, while the right hand carries the main melody. Pianists should focus on legato, smooth phrasing, and expressive dynamics. Practicing hands separately and grouping notes together helps in tricky passages. For the coda, focusing on rhythmic precision and emphasising the left-hand chords enhances performance, making the piece both technically impressive and eminently musical.

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 10 “Appassionata”

3 Etudes in D-flat Major

Franz Liszt’s 12 Grandes Etudes No. 11

As far as I can tell, the D-flat study of the 1826 version never reappeared; I think it might have been transposed and appeared elsewhere. In the event, a song-like melody unfolds in the top voice, which requires both delicacy and clarity. Although it demands a level of virtuosity, the piece is fundamentally lyrical in nature. The melody is beautifully phrased, requiring a pianist to bring out its fluidity and maintain a legato connection between notes.

While the harmonic progression is relatively simple and the structure straightforward, the expressive challenge is shaping the melody with subtle rubato and dynamic nuance, bringing out its graceful, singing quality without overemphasising any single note. The D-flat Major etude from 1826 is a refined composition, evoking a sense of youthful exuberance and lyrical elegance.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 11 in D-flat Major “Allegro Grazioso” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

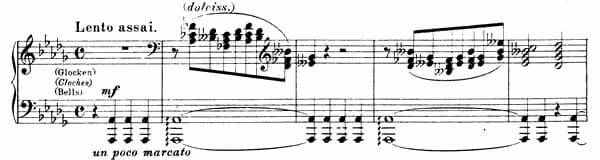

The tolling of evening bells marks the start of the eleventh study. And this figure will return throughout. There are some minor differences in the harmonic language with the later version, but the whole musical fabric is much more complex, contrapuntally, rhythmically and harmonically. As Leslie Howard writes, “before the second, grandiose, appearance of this theme, there is an extended passage at great speed which Liszt dropped in the final version.

The reason Liszt dropped this flourish in the final version possibly has to do with the title he later appended. For “Harmonies du soir” (Evening harmonies) the speedy passage would almost certainly have destroyed the mood. However, we also hear an expressive E major melody in cross-rhythms, and the demanding passages in octaves eventually lead this piece to a quiet close.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 11 in D-flat Major “Lento assai” (1837) (Wenbin Jin, piano)

As Alan Walker writes, “Harmonies du soir is like an impressionist canvas, so vividly painted that it is as if one hears not only the sounds but also smells the perfumes drifting across the warm evening air. There is an impression of bells softly ringing from a distant spire, a feature taken over from the 1837 version.” Liszt’s primary technical purpose is undoubtedly a judicious and imaginative use of pedalling. “There is here an unmistakable glimmer of Debussy’s impressionism.”

This etude is certainly different from the others in the set as it emulates a symphonic poem, generating the sound of the orchestra through only the piano. It is a completely artistic composition, with its creative elements, musical structure, and tremendous sound effects all contributing to its effectiveness. On the last page, the music grows gradually quiet, like an evening stroll at dusk. The melody simply disappears and morphs into slow arpeggios.

Franz Liszt: Etudes d’exécution transcendante, No. 11 “Harmonies du soir”

3 Etudes in B-flat Major

Franz Liszt’s Transcendental Étude No. 12

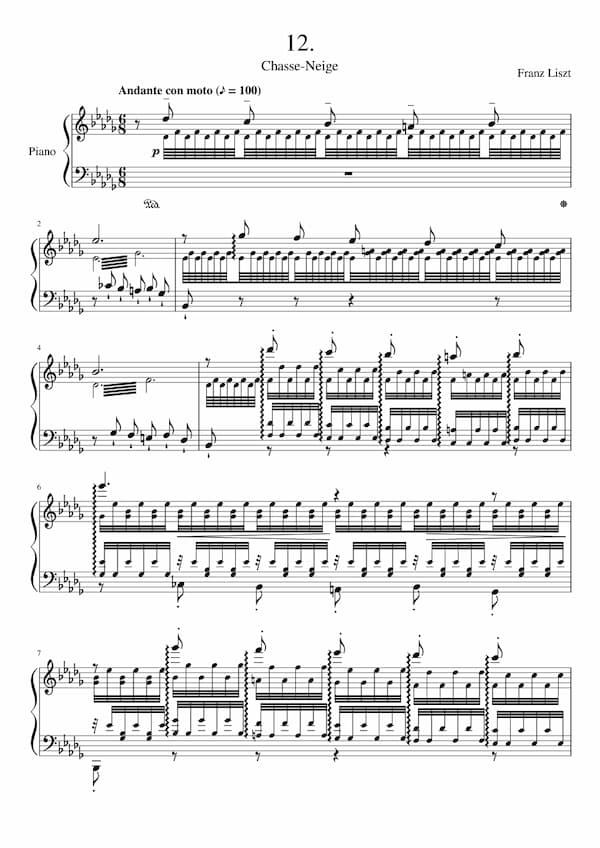

The final etude in the 1826 set, although Liszt seemed to have sketched some additional pieces, is once again a youthful exploration of virtuosic piano writing. It showcases flowing, rapid passages in the right hand. It is lyrical and less complex than the later versions, and the swirling snow-storm imagery of the later “Chasse-neige” is certainly hinted at. With its regular and formal structure, the piece focuses on thematic development rather than dramatic effect. It certainly offers insight into Liszt’s compositional voice, revealing a budding genius exploring the expressive potential of the piano with clarity and elegance.

Franz Liszt: Etudes en douze exercices, No. 12 in B-flat Major “Allegro non troppo” (1826) (William Wolfram, piano)

In his 1837 version, Liszt once again experimented with increased technical complexity. The study retains its flowing and fast passages, but the right hand now features more intricate patterns, requiring greater control and dexterity. Liszt also begins to add more contrast and drama through articulation and phrasing. The rapid passages are still prominent, but they are more fragmented and varied, laying the groundwork for the 1851 version.

Ferruccio Busoni described the Transcendental Etude No. 12, with the title “Chasse-neige” (Snow flurry) as “the noblest example, perhaps, amongst all music of a poetising nature.” He describes the work as “a sublime and steady fall of snow which gradually buries landscape and people.” This study of nature and its unique mood of desolation must rate among Liszt’s greatest studies. It is remarkable that Liszt ends a series in which virtuosity and brilliance came to dominate, not with a pyrotechnic firework but on a note of sadness.

Franz Liszt: 12 Grandes Etudes, No. 12 in B-flat minor “Andantino” (1837) (Wenbin Jin, piano)

Conclusion

The brilliant little pieces of 1826, composed when Liszt was only fifteen, are written in the manner of his teacher Czerny. They are not merely musical juvenilia but the starting point of a long process that led to the peak of Romantic piano literature. As for the 1837 version, Schumann writes, “perhaps no longer satisfied with himself, Liszt tried, in the urge to offer something of his own, to embellish them anew, and to surround them with the pomp of newly obtained virtuosity.”

Apparently, Liszt recognised that in the 1837 set, he had indulged his own unique powers in creating complexities that few others, if any, found manageable. And while the third edition of the etudes remained difficult, “they became even more refined and poetic.” A commentator wrote, “In listening to these works, we are once again reminded that Liszt was the pianist par excellence; not only the unequalled virtuoso, but also the visionary poet, ardent dramatist, and boldest of romantic innovators.”

Abram Chasins probably said it best, “In writing music that would display all these characteristics, Liszt created piano works that are as relentless in their physical demands as they are in their lyrical and imaginative demands upon the performer. To all but players of the very first calibre, they are inexorably cruel, merciless in their immediate exposure of deficiencies in musicianship, taste, tonal control or technical command!”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter