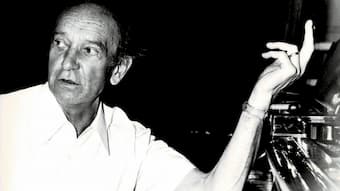

Rudolf Buchbinder © Marco Borggreve

The pianist Rudolf Buchbinder is considered one of today’s legendary performers. For over 50 years he has appeared in concerts with renowned orchestras and conductors all over the world. His broad artistic range is documented in more than 100 recordings, and his innovative interpretations of Beethoven have set new standards. His interpretations are based on meticulous study of source materials, and as an avid collector of historic scores, he owns 39 complete editions of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. With his cyclic performances of the 32 Beethoven piano sonatas, Buchbinder has contributed significantly to the development of the performance history of these works. In his lifelong exploration of Beethoven’s works for piano, he continues to find new and surprising musical and interpretive angles. “Even pieces that I have performed hundreds of times,” Buchbinder writes, “never lose their freshness to me.” Buchbinder is considered one of the elder statesmen of the keyboard, and he attributes much of his success to his teacher Bruno Seidlhofer (1905-1982).

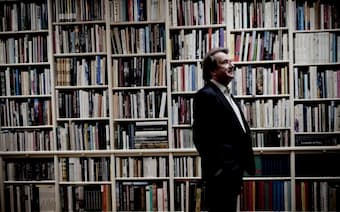

Bruno Seidlhofer

The name Bruno Seidlhofer is not usually mentioned in connection with the great pianists of the 20th century. However, he should almost certainly be considered among the most influential piano teachers. A legendary pedagogue, his students include among numerous others, Martha Argerich, Paul Badura-Skoda, Nelson Freire, Friedrich Gulda, Anton Heiler and Rudolf Buchbinder. Seidlhofer proudly suggested, “My method is not to have a method,” and his idea about music revolved around sensation and expression. A good many of Seidlhofer’s thoughts were passed down to him through his own teacher Franz Schmidt—he studied organ, cembalo, piano, cello and compositions—and his close association with the Second Viennese School around Arnold Schoenberg, and especially Alban Berg. Seidlhofer was a Bach fanatic, and he only took students who had already achieved the highest technical competence. When Seidlhofer played Bach, “his left hand played exactly in time, while the right was completely free—and all that without ever losing the tempo.”

Rudolf Buchbinder © Marco Borggreve

Buchbinder was born in the Bohemian town of Leitmeritz, but his family moved to Vienna early on. They lived in a small apartment, and “don’t ask me why,” there was a piano. “On top of the piano was a radio,” and both were like magnets for him. Buchbinder passed the junior entrance examination for the Vienna Conservatory at age 5, and in 1958 he was admitted to Bruno Seidlhofer’s master class alongside Nelson Freire and Martha Argerich. “He was a man of few words,” Buchbinder remembers, “but he was always in physical contact with his students. When he squeezed your shoulder somewhere, you realized that something was wrong with the rubato.” Interestingly, Seidlhofer did not give individual lessons. “ We were at least 10 students together, and it took all day,” remembers Buchbinder. “We all listened to each other. There was never any jealousy.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio No. 3, Op. 1, No. 3 (Josef Suk, violin; János Starker, cello; Rudolf Buchbinder, piano)

Bruno Seidlhofer and Rudolf Buchbinder

Seidlhofer’s teaching was all about the freedom of expression. According to Buchbinder, Seidlhofer was an archenemy of firm fingerings and answered a Japanese student who asked him for some: “Just throw your claws on the keyboard! See, you play with it as it has grown.” Technically weak students would not benefit from his instruction, as Seidelhofer quietly focused on refining the innate musical talents of his students. Buchbinder’s career unfolded like a continuous crescendo, and he writes “that he had the great fortune that nobody ever considered him a sensation.” Yet, he has been called “the greatest natural pianist talent,” and his artistic mantra is stated in his memoirs. “You may overindulge and get bored of some foods. But you can never overindulge when it comes to playing the masterpieces of piano literature… there is always more to be achieved.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter