Coastline in the evening light or Coastline at dusk by Caspar David Friedrich

The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) is best known for his allegorical landscapes. Contemplating nature, he sought to convey a subjective, emotional response to the natural world. He was looking not just to explore the blissful enjoyment of a beautiful view, “but rather to examine an instant of sublimity, a reunion with the spiritual self through the contemplation of nature.”

Wanderer above the sea of fog by Caspar David Friedrich

In his painting we frequently find a person seen from behind, contemplating the view. The viewer of the painting is encouraged to view the sublime potential of nature through the eyes of this observer. Friedrich painted a wide range of geographical features, and he often used the landscape to express religious themes.

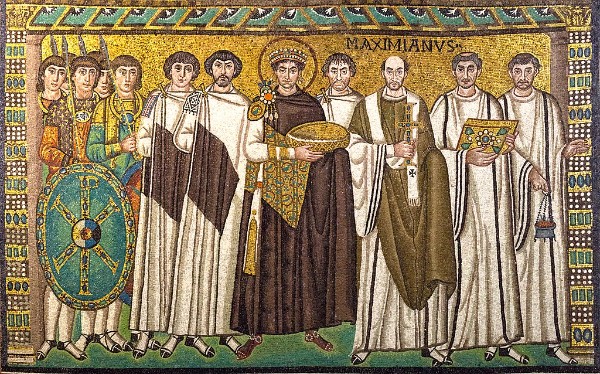

Richard Strauss

His landscapes are full of romantic feelings and many of his best-known paintings were viewed as expressions of religious mysticism. Eichendorff, as we have already seen, was the quintessential poet of the German landscape. In addition, he was a devoted Catholic, and never in doubt about his faith. The Romanticism found in David’s paintings and in his poetry serve Eichendorff to display his belief in God’s orderly world.

Richard Strauss: 4 Last Songs – No. 4. Im Abendrot (In the Evening Glow) (Renée Fleming, soprano; Houston Symphony Orchestra; Christoph Eschenbach, cond.)

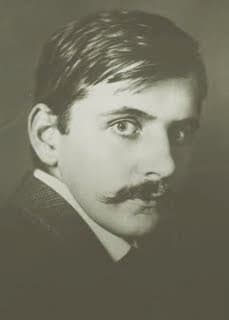

Bruno Walter

“Im Abendrot” (At Sunset) describes an elderly couple spending the quiet evening of their lives together. “Is this perhaps death?” asks the soprano, while two flutes evoke a pair of larks rising towards the heavens.

Strauss even quotes the transfiguration theme from his symphonic poem Death and Transfiguration, and on his own deathbed just a couple of months later, said to his niece: “It’s a funny thing, Alice, dying is just the way I composed it! A work of artistic purification and refinement”, “Im Abendrot” is not only Strauss’ most perfect musical offering to his beloved wife, but a touching tribute to life itself.

Wir sind durch Not und Freude | We have, of need and joy, |

gegangen Hand in Hand: | wandered hand in hand; |

Vom Wandern ruhen wir beide | From wandering rest we now |

nun überm stillen Land. | amidst the silent land. |

|

|

Rings sich die Täler neigen, | The valleys fold around themselves |

es dunkelt schon die Luft, | before the deepening gloom |

zwei Lerchen nur noch steigen | Alone two larks still soar |

nachträumend in den Duft. | Rapt in the twilight perfume. |

|

|

Tritt her und laß sie schwirren, | Stand here and let them whirl, |

bald ist es Schlafenszeit, | soon enough comes their rest |

daß wir uns nicht verirren | Would that we not lose ourselves |

in dieser Einsamkeit. | within this loneliness. |

|

|

O weiter, stiller Friede! | O utter silent peace! |

So tief im Abendrot, | Suffused with this sun’s last breath |

wie sind wir wandermüde – | Of wandering grow we so weary – |

Ist dies etwa der Tod? | Is this our sense of death? |

Bruno Walter: 3 Lieder nach Josef von Eichendorff – No. 2. Der junge Ehemann (The Young Husband) (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Wolfgang Sawallisch, piano/cond.)

Walk at Dusk (Man Contemplating a Megalith) by Caspar David Friedrich

Eichendorff first became famous for his novella Aus dem Leben eines Taugenichts (Memoirs of a Good-For-Nothing) and his poems. The Memoirs of a Good-For-Nothing, a typical romantic novella, whose main themes are wanderlust and love. The protagonist, the son of a miller, rejects his father’s trade and becomes a gardener at a Viennese palace where he subsequently falls in love with the local duke’s daughter. Since she is unattainable for him he escapes to Italy. When he returns to Vienna, he learns that his beloved is the duke’s adopted daughter, and thus within his social reach.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Considered a high point of Romantic fiction, the novella has been called the “personification of love of nature and an obsessing with hiking.” Thomas Mann called the novella a “combination of the purity of the folk song and the fairy tale.” Eichendorff made it a habit to first publish his poems as integral parts of his novellas and stories, where they are frequently performed in song by one of the protagonists. For example, the novella Good-For-Nothing alone contains 54 poems.

The evening star by Caspar David Friedrich

Eichendorff served as the inspiration for some early compositions by the conductor Bruno Walter, who offers a glimpse of how Gustav Mahler might have approached the poet. Erich Wolfgang Korngold composed his 6 Simple Songs between the ages of fourteen and sixteen. The title is somewhat misleading as the prodigy teenager brilliantly reflects the characters of each of the poem. Simplicity and beauty are portrayed through the “juxtaposition of heightened, intense fear or passion with subdued peace and tranquility.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: 6 Einfache Lieder, Op. 9 – No. 2. Nachtwanderer (Wolfgang Holzmair, baritone; Imogen Cooper, piano)

Othmar Schoeck

Eichendorff’s views on poetry appear throughout his works. Romanticism is seen in terms of a historical dialectic that transcends both, what he calls “Christianity without Christ,” and Goethe’s notion of “nature poetry in the highest sense.” Eichendorff believes that poetry is “at the heart itself religious.” He even provides his own quatrain, “Divining Rod,” which has been a key to our understanding of his poetry.

Schläft ein Lied in allen Dingen, | Music sleeps in every thing |

die da träumen fort und fort | which dreams and slumbers undisturbed, |

und die Welt hebt an zu singen, | and the world will wake and start to sing |

triffst du nur das Zauberwort. | if you but find the magic word. |

It consists of discovering the “magic word” that will awaken the “Lied” that lies dormant in all things. As such, “the divining rod of poetry will lead the reader to the spiritual source that unites man and nature with God.” The search for that spiritual source constitutes the essence of Eichendorff and his poetry.

Othmar Schoeck: 14 Lieder, Op. 20: No. 14. Nachruf (Wolfgang Holzmair, baritone; Imogen Cooper, piano)