German artist Alexander Polzin (b. 1973) first encountered Bach in his final work: The Art of the Fugue. The introduction to the ultimate Bach composition set Polzin up for a life confronting Bach and an evolution in his approach to art.

Alexander Polzin

His usual approach was to conceive of a theme that would convey the image he wanted to portray. With Bach however, he made many attempts to translate what he was hearing in the music into visual arts and failed over and over again.

He successfully did portraits of Schumann and Beethoven, and even of Orpheus, but Bach continued to elude him. Finally, he made up his mind that Bach is the God of Music and therefore couldn’t be pictured.

This, however, as a resolution, didn’t last long. But we digress.

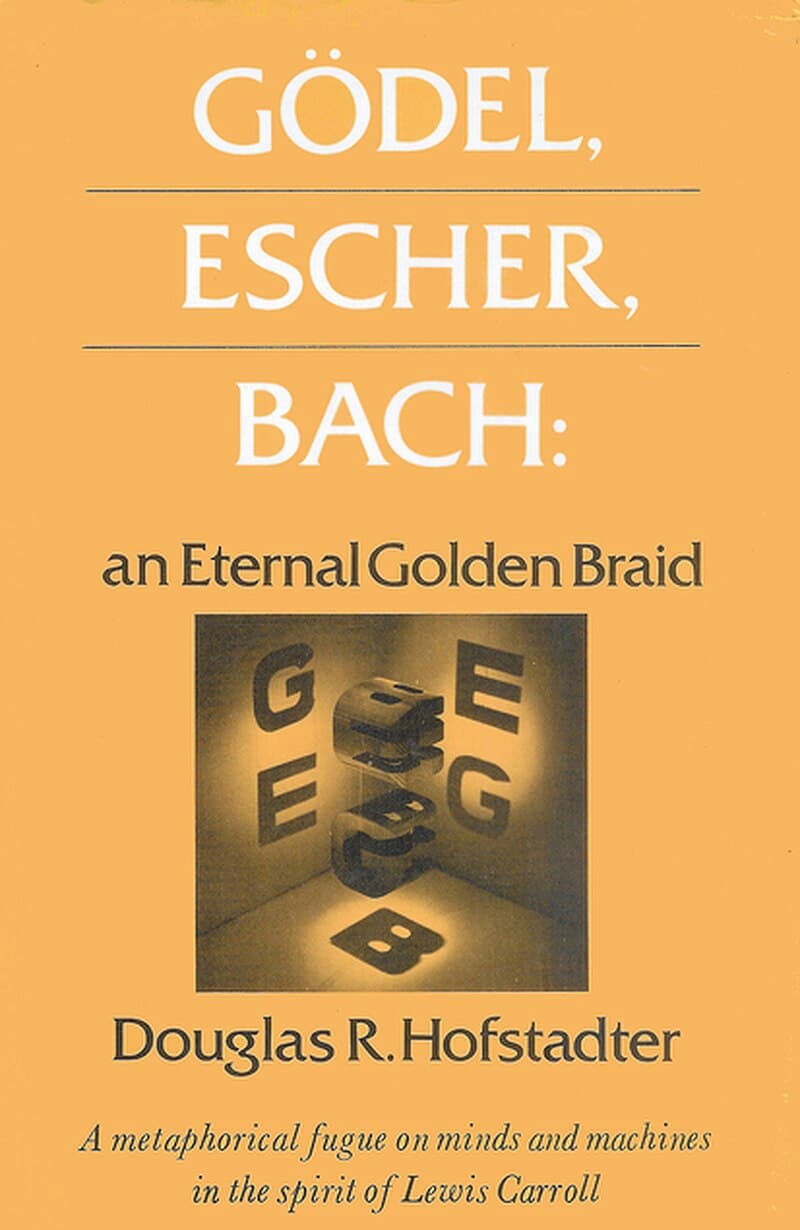

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and East Germans were now free to travel for the first time since 1961. The 17-year-old Polzin promptly started moving, with his first stop in French Polynesia. While travelling, his book companion was Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach, which looked at mathematics, symmetry, and intelligence through the lives and works of logician Kurt Gödel, artist M.C. Escher, and composer J.S. Bach.

Hofstadter: Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (photo by Douglas Hofstadter)

In the South Pacific, Polzin was struck by the incredible variety of natural forms, both on land and in the sea. This same infinite variety is how he has come to conceive of Bach, and he fears (and somewhat hopes) that this will be his destiny: to be ever intertwined with the immortal composer.

His first Bach work was a painting, Bach at Pomare IV, created in 1994. He painted one image after another on top of the last, creating an abstract result from layered non-abstract images.

Bach at Pomare IV, 1994 (photograph by the artist)

Once he brought Bach to the world of dimensional sculpture, his freedom to explore knew few bounds. He creates to the music of Bach and his Bach sculptures bring out what he listens to.

With his training as a stonemason, Polzin’s approach to art is through a medium that is particularly difficult to manipulate. It’s large, it’s heavy, and has an individual character. Accordingly, his modelling material is equally difficult. Although most sculptors work in clay before their busts are cast, Polzin works in wood. Specifically oak, one of the hardest woods of Europe. Polzin sources his wood from the trees in the forest, working with the local forester to choose the tree. He said there’s a kind of hubris in this – taking a tree, which is already a work of art and maybe 100 to 150 years old, and then making a different work of art out of it.

Oak is very difficult to work with, starting with the hardness of it wood; in addition, the acid in its wood quickly blunts the woodworking tools. Polzin says he has a dialogue with the wood, seeking how to impose his vision on what is already a perfect sculpture of a tree. Accordingly, there may be many tree elements that come through his sculptures, as in Bach III below.

Bach I, done in blue glass, can glow in the light.

Bach I © Norbert Banik

Bach I, glowing © Norbert Banik

Bach II seems to be connected with the undersea world that Polzin saw in French Polynesia. Bach’s mind is open to the world, taking in everything and channelling it through his polished perception. A brain coral, perhaps?

Bach II © Norbert Banik

Bach III, completed in 2023, will be installed at the Royal Academy of Music in London. This is a larger image – if Bach I and II were appropriate for collectors, this Bach is for public display. The texture of the wood is more visible here – both on his cheek and in his hair. This will be displayed on a plexiglass plinth and is intended to be viewed from 360°, including from below. With plexiglass’ ability to capture light, there should also be a glowing effect with this bust.

Bach III (photo by Alexander Polzin)

Polzin doesn’t conceive of a unified Bach but a sectional Bach: The Bach of The Art of Fugue is different than the Passion Bach, or the Keyboard Bach. All these different Bach characters may be at the root of Polzin’s inability to focus on one theme for his Bach portraits.

For Polzin, sculpture has the possibility of illustrating contracting or opposing ideas. Whereas poetry cannot put both love and hate in a single word, sculpture can bring these together. When we spoke, Polzin had just received Bach IV from the foundry, and in it he was able to evoke a double Bach.

Bach IV, 2024 (photo by Alexander Polzin)

You can see Back’s profile at the right, but in the centre, you can see another Bach, looking in a different direction. Polzin said that this kind of double imagery, a kind of dimensional cubism, was only achievable in glass.

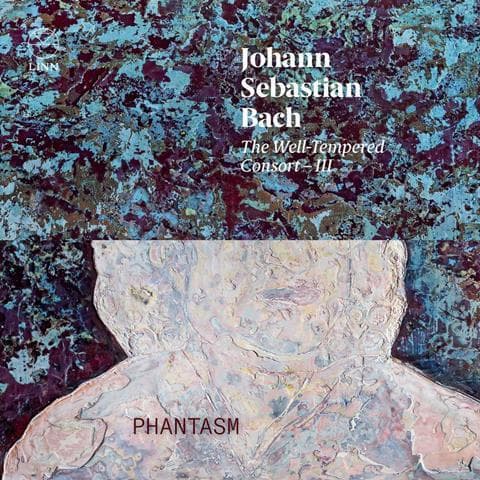

Another Bach from his hands was the cover for a recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, arranged for chamber ensemble. Polzin held an exhibition, Bach and Beauty, in New York in 2023 in conjunction with Laurence Dreyfus and Phantasm.

Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, 2023 (photo by Alexander Polzin)

J.S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, BWV 870-893: Fugue No. 3 in C-Sharp Major, BWV 872 (arr. L. Dreyfus for chamber ensemble) (Phantasm; Laurence Dreyfus, cond.)

Recently, he worked with the pianist Filipo Gorini on Gorini’s The Art of Fugue Explored. Gorini has been working on Bach’s monumental work for over a decade.

J.S. Bach: Die Kunst der Fuge (The Art of Fugue), BWV 1080 – Contrapunctus I (Filippo Gorini, piano)

As an extension of his playing, Gorini sought a dialogue with the current artists who encounter Bach, including Polzin, pianist Alfred Brendel, stage director Peter Sellars, architect Frank Gehry, cellist Steven Isserlis, mathematician Betül Tanbay, and many others. Each interlocutor comes at Bach from a different perspective, and much like Polzin’s own work on his Bach problem, comes to different conclusions about their work and Bach.

In Paris, Polzin worked with Gorini on an Artists Talk entitled Art of the Fugue, which was an exhibition of Polzin’s work followed by a performance of The Art of Fugue by Gorini. The audience was split between those who had come to see Polzin’s work and those who came for the music. For Polzin, it was interesting observing the audience: those who came for an artist’s exhibition and who ended up in a piano recital started off irritated, annoyed, and impatient to leave. By the end, 90-some minutes later, they were still held, captured by the music.

J.S. Bach: Die Kunst der Fuge (The Art of Fugue), BWV 1080 – Fuga a 3 Soggetti (Contrapunctus XIV) (Filippo Gorini, piano)

And so Polzin is held by the contradictions of Bach – Bach the subtle master of counterpoint, Bach the artist of the fugue, Bach the confounder of expectations, Bach the magician.

Polzin’s Bach III will be installed in the foyer of the Royal Academy of Music on 13 June 2024. He is currently working on Bach V.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter