Very few people are actually born to become composers, and composers frequently struggle financially in society. In fact, the starving artist was a popular trope in the late 18th and 19th centuries. It was suggested that artists lived in poverty or under severe financial strains in order to focus on their artwork.

As a cultural historian wrote, “a minor artist with no money goes as hungry as a genius. What drove them to do it? I believe that such people were not only choosing art, they were choosing the life of the artist. Art offered them a different way of living, one that they believed more than compensated for the loss of comfort and respectability.” We thought it might be fun to look at 10 composers who learned a trade away from music or found employment in completely different areas.

Alexander Borodin the Chemist

A commemorative coin of Alexander Borodin

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887) always regarded medicine and science as his primary

occupation. In fact, he only wrote music in his spare time or when he was ill! He began his study of chemistry as a teenager, and in 1850 he entered St Petersburg’s Medical-Surgical Academy, the training ground for physicians in the tsar’s service. He took courses in natural sciences and anatomy, but chemistry was his real passion. Borodin worked under the supervision of the famed Nikolay Zinin, holder of the chair of chemistry and a brilliant scientist. Zinin was seriously pleased with Borodin’s ability but troubled by his interest in music.

On one occasion, Zinin publicly announced in his lecture hall, “Mr. Borodin, busy yourself a little less with songs. I’m putting all my hopes in you as my successor, but all you think of is music: you can’t hunt two hares at the same time.” Borodin headed the advice, and once he had ceased to practise as a physician, he focused on chemical research and teaching. As a chemist, he is best known for his work on organic synthesis, including being among the first chemists to demonstrate nucleophilic substitution, as well as being the co-discoverer of the aldol reaction. Borodin also founded the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg, and luckily he found a little time to compose.

Alexander Borodin: String Quartet No. 2

Charles Ives the Insurance Professional

Charles Ives’ insurance office

George Edward Ives, father of Charles Ives (1874-1954) was the most influential musician in the Danbury Connecticut region. George was determined that his son should take up a career as a concert pianist, but the rebellious son decided to go into business. He left Yale University to take up a job as a clerk with the Mutual Life Insurance Company. He reasoned, that if “a composer has a nice wife and some nice children, how can he let them starve on his dissonances?”

Charles eventually had a nice wife and nice children, and as he rose in the insurance ranks he founded his own company “Ives & Myrick” in 1907. It became the largest insurance agency in the United States, with a professional sales force turning the agency into one of the most profitable companies in the country. He even introduced the concept of estate planning, detailing the process of anticipating the disposal of an estate during a person’s life. Ives strongly believed that “there was not a service that I could render to my fellow man that was more important than the business of life insurance, because it instilled in the soul and mind of my fellow man the responsibility of meeting his obligations.” And he continued to compose only in his spare time.

Charles Ives: Three Places in New England

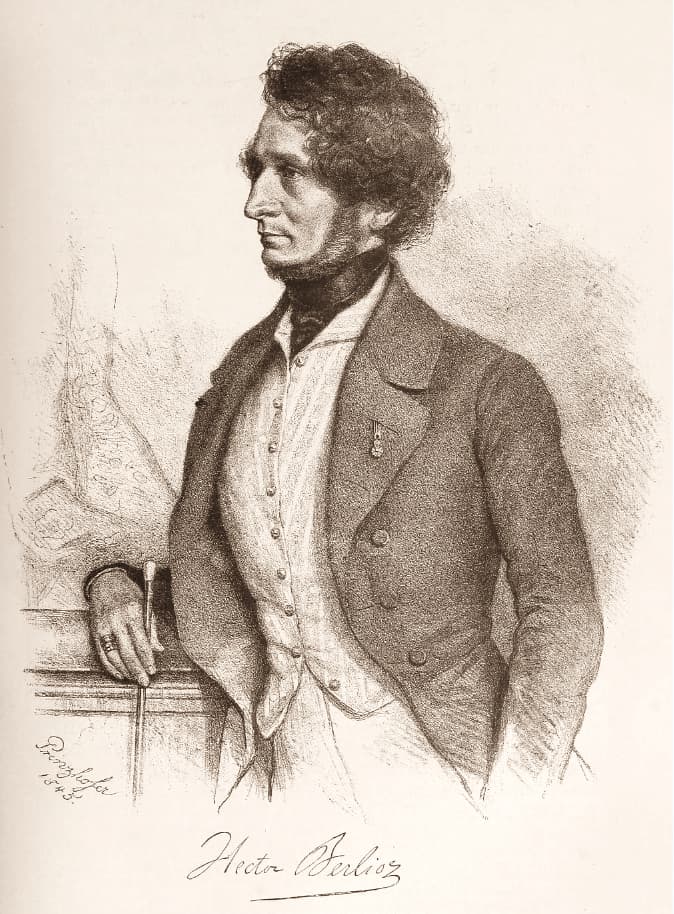

Hector Berlioz the Surgeon

August Prinzhofer: Hector Berlioz, 1845

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) was destined to become a medical doctor, as his father Louis Berlioz was a respected physician who is credited as the first European to practise and write about acupuncture. As a young boy, Berlioz enjoyed geography and Latin, but his father had clearly planned a medical career for him. As such, he enrolled at the School of Medicine at the University of Paris. He arrived in Paris in November 1821 and signed up regularly for attendance at classes, including the dissection amphitheatre.

As he wrote in his Mémoires, “the thought of being a doctor, of studying anatomy, of dissecting bodies, of witnessing horrific operations, instead of surrendering body and soul to music, the sublime art whose grandeur I could already imagine! No! This seemed to me a turn the natural order of my life upside down.” Since his father sent him an ample allowance, Berlioz preferred to take full advantage of the cultural and musical life of Paris. Berlioz did graduate from medical school in 1824, but immediately decided to abandon medicine. Louis Berlioz was not happy and the allowances stopped, and the starving artist trope was once again confirmed. As far as the real job is concerned, Berlioz initially made his money as a music critic.

Hector Berlioz: Le Corsaire, “Overture”

Philip Glass the Taxi Driver

Philip Glass © blog.sonos.com

We already established that it’s not easy to make a living being a composer. We just need to ask the pioneer of minimalist music, Philip Glass. He supported himself by working as a plumber, furniture mover, and taxi driver. “I was careful,” the composers explained, “to take a job that couldn’t have any possible meaning for me.” Glass got his taxi-driving license and drove his yellow taxicab through the 5 Boroughs at night. He gave up his previous plumbing job because swinging heavy wrenches all day made it rather difficult to play the piano in the evening. There were some drug-related robberies and daily violence, but for Glass “driving a taxi represented a fantastic slice of life.”

New York City taxi cabs

Even after he had achieved fame and notoriety with his opera Einstein on the Beach in 1976, he still continued to ply his blue-collar trades. He kept on driving his cab but as more and more commissions trickled in, Glass finally considered the possibility that his taxi driver’s license might not be needed anymore. He related that he understood that he had arrived as an artist when a woman tapped on the side of his cab and told him, “you have the same name as a very famous composer.”

Philip Glass: Einstein on the Beach, (excerpt)

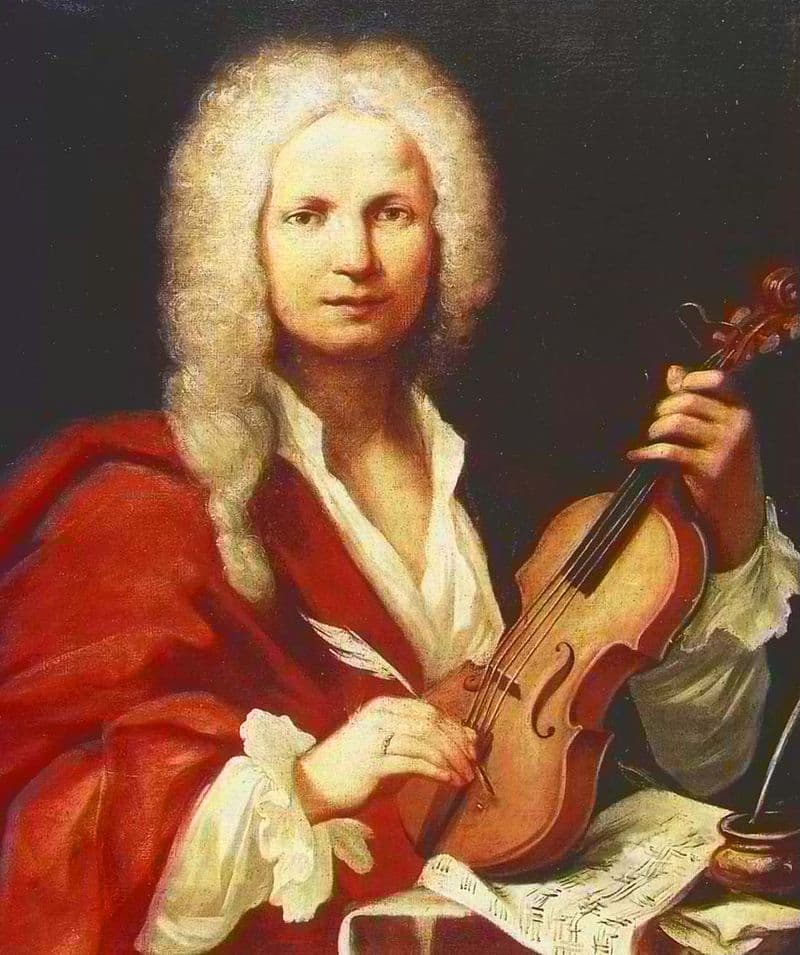

Antonio Vivaldi the Priest

Antonio Vivaldi, 1723

In 1693, at the age of 15, Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) began studying for the priesthood, one of the few career options open to him. The priesthood enabled low-born young men like Vivaldi to get a head start in life. He was ordained in 1703 at the age of 25, and shortly after was appointed chaplain and Violin Master at a local orphanage called the Pio Ospedale della Pieta, or the Devout Hospital of Mercy in Venice. That particular appointment as a priest and music master gave him a nice salary of 60 ducats, and for about a year he was very busy in both professions.

However, after just a year of being a priest, Vivaldi requested a dispensation from celebrating Mass due to his poor health. From birth he had been afflicted with a serious, unknown, health condition thought to be a form of asthma. All that is known about the mysterious illness comes from the letter Vivaldi wrote asking for the dispensation, in which he referred to it as a “tightness of the chest.” Not everybody believes that health was the real reason, and some voices suggest that he was kicked out of the priesthood for abusing the choir girls. It’s probably just silly gossip, but music seemed to have had a stronger pull. The one fact remains, however, even after Vivaldi stepped down from his liturgical duties, he never stopped being a priest.

Antonio Vivaldi: Stabat Mater

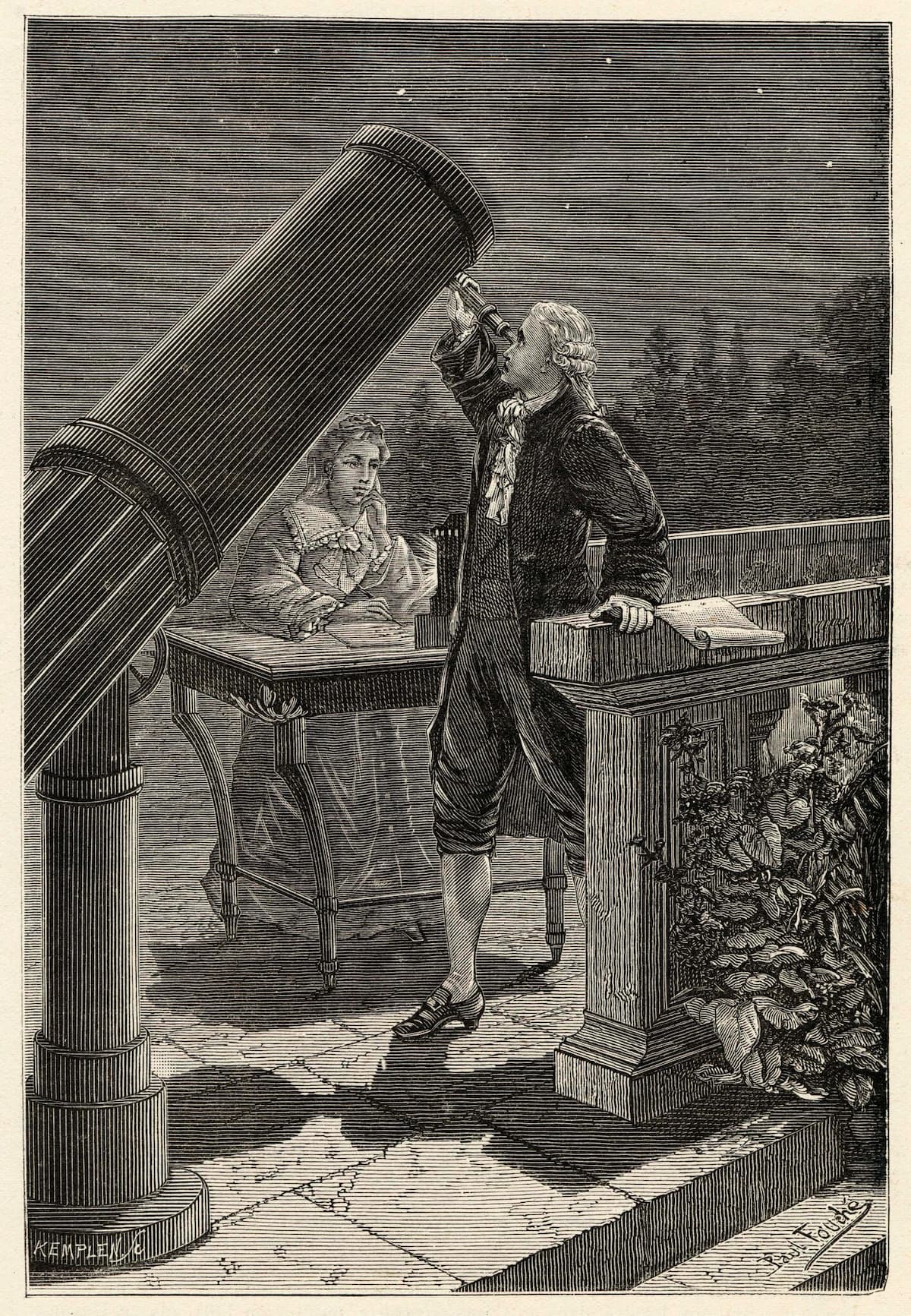

William Herschel the Astronomer

William Herschel

William Herschel (1738-1822) was the most famous observational astronomer of his time. When he looked through his homemade telescope on 13 March 1781 he noticed something decidedly peculiar. One of the celestial bodies moved rather oddly across the sky, and Herschel thought that he had found a new comet. However, he quickly understood that he was not looking at a comet or a star, but at a new planet beyond the orbit of Saturn. It was the first planet to be discovered since antiquity, and it took much discussion before it was named after the Greek god of the sky, Uranus.

Herschel was a Fellow of the Royal Society, and officially appointed “The King’s Astronomer.” He received extended funding for the construction of telescopes, and during his lifetime he built well over 400 such instruments. In addition, Herschel was an accomplished musician, taking on duties as an organist and solo violinist with the Bath orchestra. Not to be outdone, Herschel also dabbled in composition when he was not looking at the stars, and penned 24 symphonies and a substantial number of concertos for oboe, violin, viola, and organ. He also wrote a number of solo works for organ and harpsichord, as well as various sacred vocal works including psalms, motets, and sacred chants.

William Herschel: Symphony No. 12 in D Major

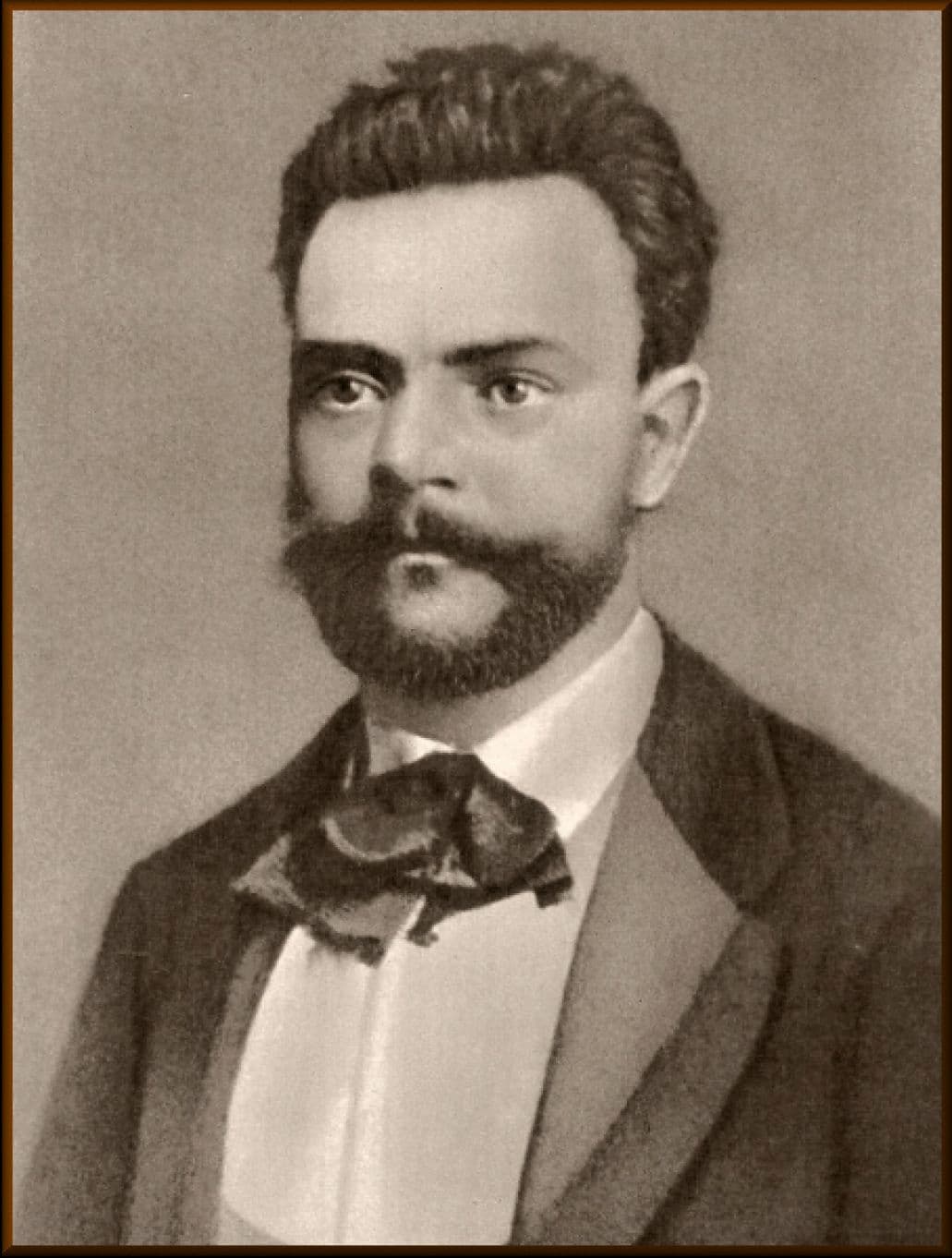

Antonín Dvořák the Butcher?

Dvořák in 1870

Basically, all of Antonín Dvořák’s relatives were butchers or innkeepers, and it was automatically assumed that the first-born child would inherit the business. Mind you, in addition to the butchers’ trade, the Dvořák family also sported another talent; a flair for music. Music was a great way of making a bit of extra money in the pub, but it was never considered a respectable job. For well over one hundred years, biographies of Dvořák included a section on the composer’s apprenticeship as a butcher in the market town of Zlonice in the Central Bohemian Region.

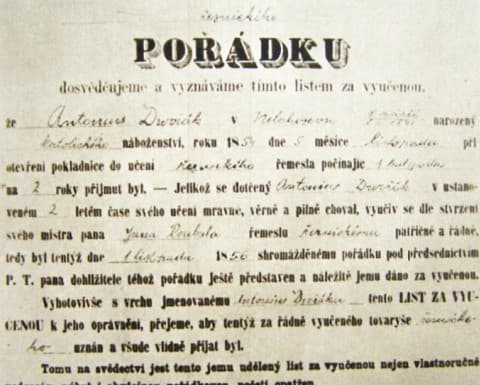

Dvořák’s butcher certificate

The assumption that Dvořák trained as a butcher was supported by a certificate of apprenticeship discovered in a private collection. That particular document was photographed and reproduced but has since mysteriously disappeared. Scholars have cited some problems with that particular document, as the mentioned master butcher Roubal was not among the names of Zlonice tradesmen. Also, in the town records, Dvořák’s name does not appear on the list of Zlonice apprentices. Most scholars agree that the document is actually a forgery, “made using a blank form already signed in advance by three masters of the Zlonice builders guild.” One thing is sure, Dvořák never made money from the butcher trade, but I bet his sausages would have been first class.

Antonín Dvořák: String Quintet No. 2 in G major, Op. 77

Emmanuel Chabrier the Civil Servant

Sketch of Emmanuel Chabrier by Édouard Detaille

Born into a family of jurists and tradesmen in Ambert, a small village in the Auvergne, Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894) showed great musical promise at an early age. He started piano lessons at six and soon thereafter composed his first short dances for piano. He even published a work entitled Aïka at the age of 14, and his grand valse “Julia” was officially designated as his opus 1. Despite his musical talents and publications, Chabrier was destined by family tradition for law studies.

After moving to Paris in 1857, Chabrier began his law studies and within three years obtained a position in the Ministry of the Interior. He remained a civil servant for the next 19 years, and apparently “was valued by his superiors for clerical meticulousness and accuracy, his calligraphic hand in correspondence and his attention to detail.” A clerk by day and a musician by night, Chabrier continued his musical activities, but work at the ministry severely restricted his compositional activities. Thankfully, however, he did find time to compose a number of memorable works.

Emmanuel Chabrier: España

César Cui the Military Engineer

César Cui

César Cui’s (1835-1918) father was of French descent, and he settled in Vilnius after the defeat of Napoleon in 1812. His mother hailed from Lithuania, and young César was sent to St Petersburg in 1850 to study at the Chief Engineering School. Upon graduation, he embarked on a military career in 1857 as a fortifications instructor at the Nikolayevsky Engineering Academy. Cui met Balakirev and became friendly with all members of “The Five.”

Cui’s first operatic project “A Prisoner in the Caucasus,” was based on a libretto fashioned by a fellow student at the military academy. Musical activities aside, Cui became a professor of military engineering in 1880 and was eventually promoted to the rank of general in 1906. He authored a number of textbooks on military fortifications, based on his direct experience of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which were widely used and went into several editions.

César Cui: A Prisoner in the Caucasus, “Air du prisonnier”

Ignacy Jan Paderewski the Politician

Paderewski giving a speech in New York, 1919

At the height of his musical success in 1919, the exceptional pianist and composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) became the prime minister and foreign minister of Poland, and he represented his native country at the Paris Peace Conference. However, Paderewski had already played a prominent part in the political life of Poland, giving voice to the public discontent of a nation without political status. He was active in fund-raising and lobbying during the war years, and he secured the support of American President Woodrow Wilson.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, Polish independence was one of its stated aims.

The Peace Treaty was not favourable to Poland, and Paderewski resigned in December 1919. However, he was back in the political spotlight in the summer of 1921, when the Red Army advanced on Warsaw. This time Paderewski served as Polish delegate of the Conference of Ambassadors. The entire process was a political minefield, and he resigned from this post in December 1920. Paderewski successfully played the role of a respected elder statesman, but he got involved in politics again in his later years. I suppose, music was somewhat less hazardous than politics, and it probably paid better.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Great article! You may want to add Giovanni Battista Viotti (12 May 1755 – 3 March 1824) to this list. He was a great violinist-composer, the Father of Modern Violin Playing, and a wine merchant. He’s best known for his Violin Concerto #22 in A minor, a favorite of none other than Johannes Brahms.