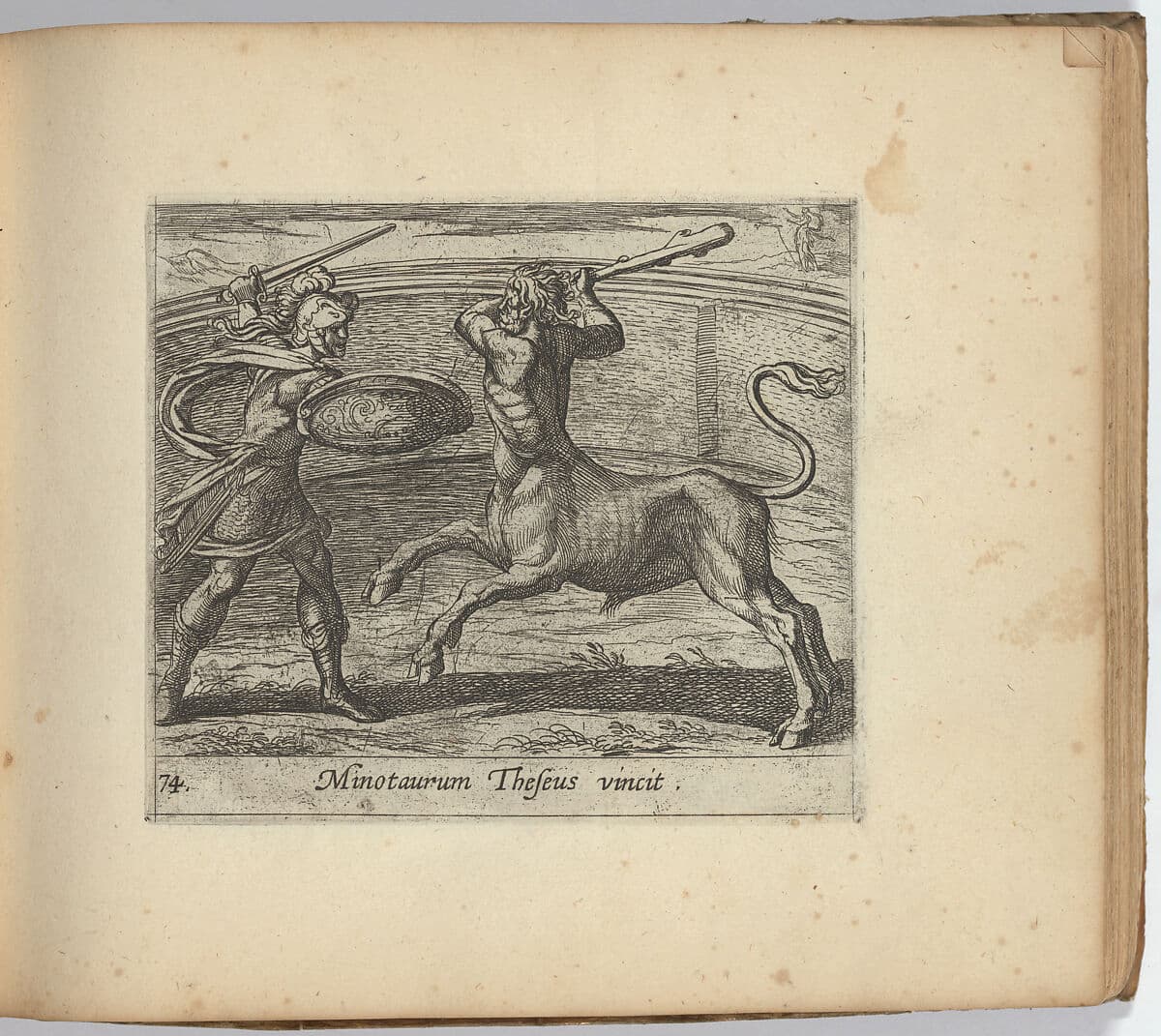

The illicit child of Pasiphaë, wife of King Minos of Crete, and a snow-white bull intended for sacrifice to Poseidon, the Minotaur, half-man half-bull, actually had the given name of Asterius (star). He was ungovernable, so Minos created a labyrinth to imprison him. The Athenians, in payment for the death of Prince Androgeus, son of Minos, had to give Minos seven of their best youths and maidens, who were fed to the minotaur. The third time the call came for the sacrificial donation, Prince Theseus joined the boat bringing the victims and, with the help of Ariadne, Minos’ daughter, he defeated the Minotaur. Ariadne left with Theseus as he returned to Athens, but he abandoned her on the isle of Naxos.

Pasiphaë and the baby Minotaur, 340–320 BCE (Paris, Cabinet des Médailles)

Kent Olofsson: Treccia – No. 7. Minotaur Labyrinth

Kent Olofsson’s series of works for solo instruments, all called Treccia, includes one for percussion on the Minotaur’s labyrinth. It’s played on 3 kinds of instrumental materials: metal, wood, and drums, each of which has instruments in the low, middle, and high registers. The work is built on long processes of rhythmic layers, which are also independent in their speeds. Once the instruments are chosen for the performance, the percussionist is free to pick the instruments he wants to use. Timbre is an important part of this work.

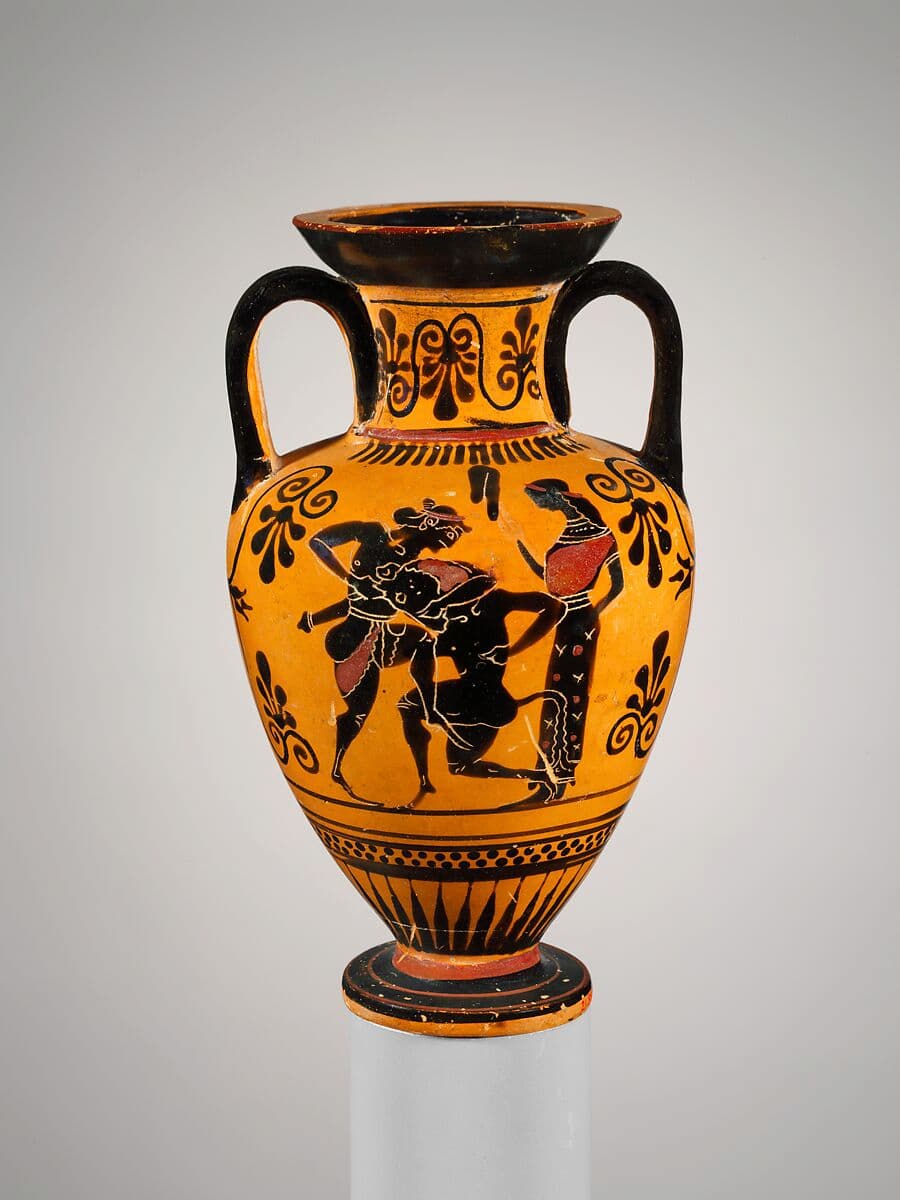

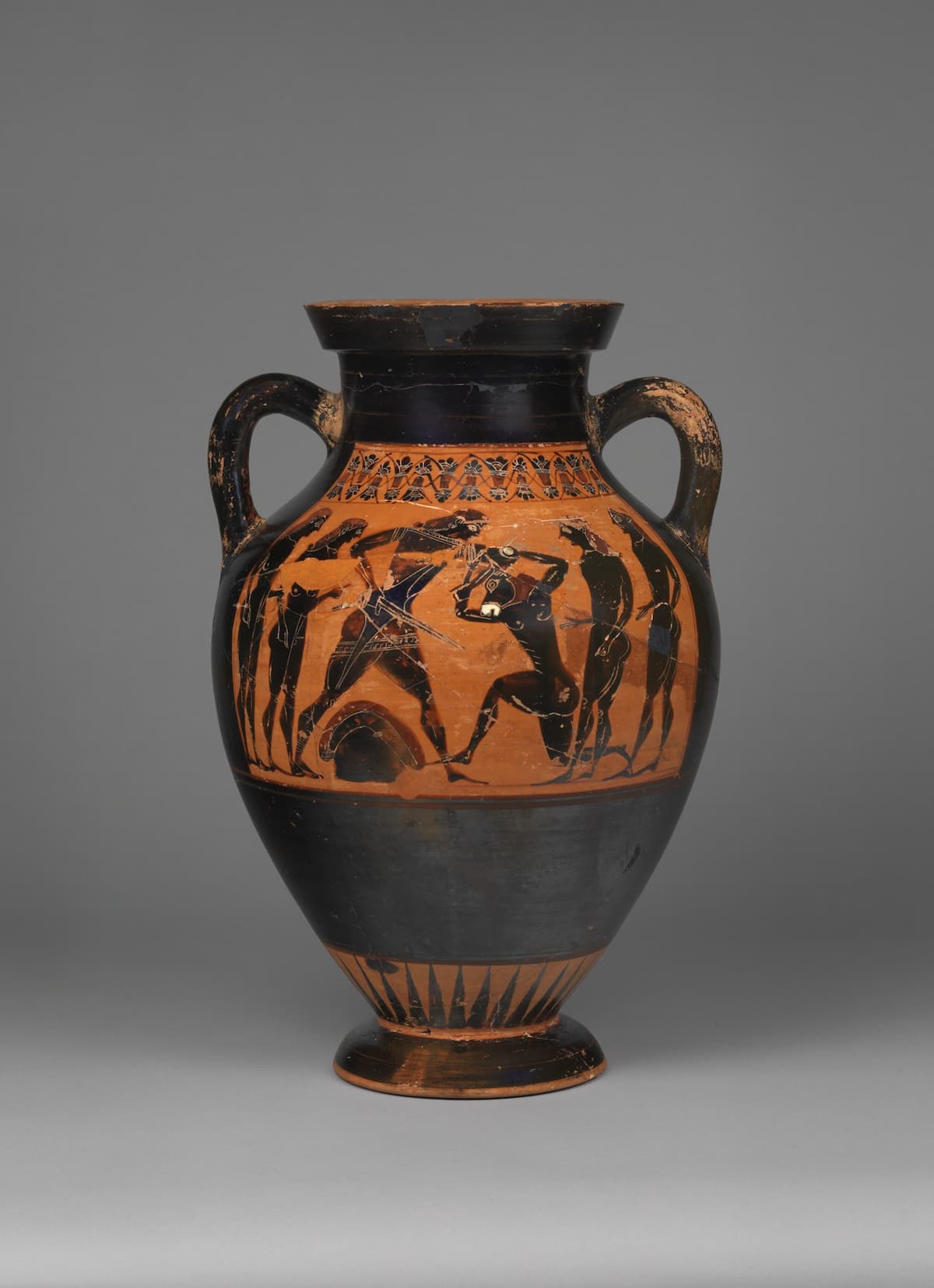

The Edinburgh Painter: Theseus and the Minotaur with Ariadne, ca. 500 BCE (Metrpolitan Museum of Art)

Kent Olofsson: Treccia – No. 7. Minotaur Labyrinth (Jonny Axelsson, percussion)

Carlos Franzetti: Minotaur in the Labyrinth for 3 Pianos

Carlos Franzetti’s 2020 Minotaur in the Labyrinth is a work for 3 pianos, commissioned by Ted Viviani. The exigencies of Covid meant that it was not possible to get three pianists together for the recording, so Allison Brewster Franzetti recorded all three parts. The animalistic ferocity of the opening in awe-inspiring the six hands of three pianists.

Black-figure panel amphora: Theseus and the Minotaur, ca. 545–535 BCE (Princeton University)

Carlos Franzetti: Minotaur in the Labyrinth for 3 Pianos – I. Minotaur and Theseus (Allison Brewster Franzetti, pianos)

Ned Rorem: String Quartet No. 4 – I. Minotaur

Although he initially based the ten movements of his string quartet on specific works of art by a single artist, American composer Ned Rorem eventually withdrew those art titles and replaced them with more generic descriptives – thus the first movement, Minotaur, has become Ugly and relentless.

Picasso: The Minotauromacy, 1935 (Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ned Rorem: String Quartet No. 4 – I. Minotaur (Emerson String Quartet)

Chia-Ying Lin: Intermezzo to the Minotaur

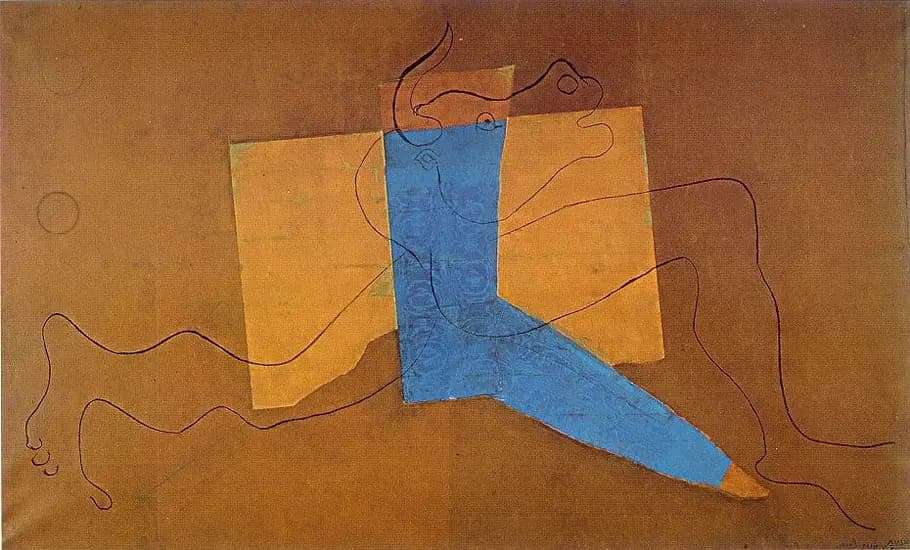

Picasso was fascinated by the Minotaur and it became a recurring feature in his artwork starting in the 1920s and extending into the 1950s, appearing in about 70 different pieces. In this work from 1928, the minotaur is reduced to a line defining two legs and a bellowing horned head, overlaid with a slash of blue and gold.

Picasso: Le Minotaur, 1928 (Paris, National Museum of Modern Art, Pompidou Centre)

In her work Intermezzo to the Minotaur (2019), Chia-Ying Lin picks up on Picasso’s ambiguity, where the creature is poised between the divine and the bestial. She sees the Minotaur struggling, in the image, against the confinement of the colour paper. He’s fluid and the paper is edged and rigid. The composer notes: ‘These aspects inform the narrative and structure of my piece, where different musical characters—one being celestial and fluid, and the other being brutal and bull-headed strong—are juxtaposed. The discontinuity and continuity in the narrative, together with different musical metaphors, are explored to symbolise the animal instincts and irrationality”.

Chia-Ying Lin: Intermezzo to the Minotaur (members of the Philharmonia Orchestra; Geoffrey Paterson, cond.)

Lucia Długoszewski: Openings of the (eye) – I. Discovery of the Minotaur

The collaboration between the dancer Erick Hawkins and the composer Lucia Długoszewski brought together two modernists. He’d been a member of Balanchine’s American Ballet and Martha Graham’s company (and had recently divorced her), and she was a student of Edgard Varése. She started working as his accompanist and soon started writing music for his performances. One of the first pieces she created for his choreography was based on mythological themes, Openings of the [eye]. The work was based on his choreography, rather than the other way around, and so the music is full of instability and blurred sounds. Glissandos, trills, ricochets, vibrato all have a place in her piece.

Antonio Tempesta: Theseus and the Minotaur (Minotaurum Theseus vincit), from The Metamorphoses of Ovid, 1606 (Metropolitan Museum)

Lucia Długoszewski: Openings of the (eye) – I. Discovery of the Minotaur (Hashtag Ensemble)

Elliott Carter: The Minotaur

We’ll close our survey of the man/beast with an unrepresentative early work by Elliott Carter. In 1947, setting a scenario conceived by George Balanchine, New York composer Elliott Carter wrote the ballet The Minotaur on a commission by Lincoln Kirstein. Bernard Holland, in his review of a performance in 1988 for the New York Times, summarized it as “This is a powerful score, one able to imply the ballet’s pictorial events with appropriate musical colors and rhythmic variety. It also offers the unconverted audience a clearer look into Mr. Carter’s muscular and energized world. The restless changes of timbre, movement and mood are recognizable, but in The Minotaur they can be seen in a slightly defoliated setting, free of the near-impenetrable underbrush of crossing, meshing and conflicting motifs in his later music, textures that defeat so many contemporary ears.”

Edward Burne-Jones: Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, tile design, 1861 (Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery)

Elliott Carter: The Minotaur: Scene 2 – Before the Labyrinth: Theseus fights and kills the Minotaur (as his movements are transmitted to Ariadne who is holding the other end of the thread) (New York Chamber Symphony; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

The Minotaur fascinated artists and sculptor, musicians and composers, who all look at this half-man half-bull both in trepidation and admiration. Picasso saw much of his own character in the wild animal – viral and ferocious to whom sacrifices had to be made. Other artists have looked at it from the other side. 500 BCE, the Minotaur was the monster and it was Theseus who was the ideal Athenian – fighting monsters to save his people.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter