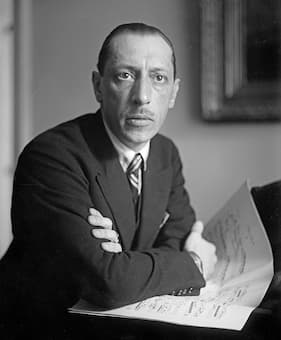

Portrait of Igor Stravinsky, c. 1920 by Picasso

Igor Stravinsky had a vast appetite for literature. That appetite basically reflected his constant desire for learning, exploring, and for making new discoveries. Forced into exile by World War I, Stravinsky initially found inspiration in Russian folklore. A collection of old folk songs he gathered during his final trip to Kiev provided the basis for a number of compositions from his Swiss period. The most important work to emerge was Les Noces (The Wedding), a ballet and orchestral concert work scored for percussion, pianists, chorus, and vocal soloist.

Les Noces

These dance scenes with song and music describe a Russian peasant wedding, and present a unique mix of genres. The composer suggested that he got the idea for the work from reading collections of “two guardians of the Russian language and soul” Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasiev and Pyotr Vasilievich Kireyevsky. “I wanted to retain something along the lines of a pagan ceremony, at my own discretion using ritualistic elements of the ages taken from Russian folk customs.” While initial reception of the work was mixed, scholars today consider Les Noces “in many respects the most radical, the most original and conceivably the greatest of them all.”

Igor Stravinsky: Les Noces (Galina Bojko, soprano; Margarita Maruna, mezzo-soprano; Egils Siliņš, bass; Ludovit Ludha, tenor; Ernst Senff Choir; Piano Circus Band; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Vladimir Ashkenazy, cond.)

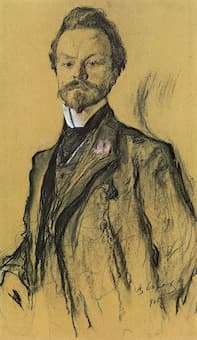

Konstantin Balmont

Igor Stravinksy composed his cantata Le Roi des étoiles for male chorus and orchestra around the time of his three famous Russian ballets, The Firebird, Petrushka and Le Sacre du printemps. Originating in 1911, it was first performed only 30 years later, and it has gained the dubious notoriety as “one of Stravinsky’s least frequently heard works.” For his literary source, Stravinsky drew once again on the works by the Russian symbolist poet and translator Konstantin Balmont (1867-1942). A major figure of the Silver Age of Russian Poetry, Balmont’s euphonic poetry replete with musical images and symbols greatly appealed to Stravinsky. Stravinsky was drawn to the “The King of Stars” because of “the particular nature of its rhthm and the capriciousness of its sonority.” The poet uses bleak images of the Apocalypse in a series of expressive comparisons and metaphors, and Stravinsky “conveyed an image of eternity by using rhythmical, triumphal choral scansion.” In contrast to his contemporaneously composed ballets, Le Roi des étoiles hints at the tonal language of Scriabin and Debussy. As such, it is hardly surprising that the work is dedicated to Claude Debussy, whom Stravinsky first met in Paris in 1910.

Igor Stravinsky: Le Roi des étoiles (South West German Radio Vocal Ensemble; South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Michael Gielen, cond.)

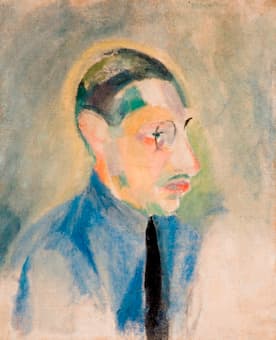

Portrait of Stravinsky by Robert Delaunay

Passing through Genoa on his way from Venice to Nice in 1925, Stravinsky stumbled on a bookstall and found a volume about the life of Francis of Assisi. “I read the book the same evening,” reported Stravinsky, “and I was stunned to read French was, for Saint Francis, the language of poetry, the language of religion, the language of his best memories and most solemn hours, the language to which he had recourse when his heart was too full to express itself in his native Italian, which had become for him vulgarized and debased by daily use; French was essentially the language of his soul.”

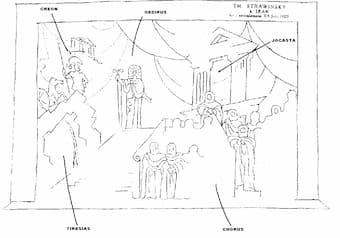

Stage scetch for Oedipus Rex

At that time, Stravinsky decided to compose a large-scale dramatic work. However, as he realized, “the voice was not located in the Russian of his childhood, or the French, German, and Italian he now more regularly spoke, but in ancient Latin.” Stravinsky wrote, “it had the great advantage of giving me a medium not dead but turned to stone and so monumentalized as to have become immune from all risk of vulgarization.” Oedipus Rex is essentially an opera about opera, and a play about a play. When Arnold Schoenberg first heard the work he wrote, “here everything is inside out; an unusual piece of theatre, an unusual production, an unusual denouement, unusual vocal writing, an unusual vertical, unusual counterpoint and unusual instrumentation.” While returning to ancient tragedy, “Stravinsky returns to the fundamental problem of the thinkers of the ancient world—the problem of Fate. And thanks to this ambiguous viewpoint, it towers mightily in all its glory.”

Igor Stravinsky: Oedipus Rex – Prologue – Act I (Michel Piccoli, narrator; Thomas Moser, tenor; Jessye Norman, soprano; Siegmund Nimsgern, bass; Roland Bracht, bass; Alexandru Ionita, vocals; Bavarian Radio Chorus; Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Colin Davis, cond.)

T.S. Eliot

During his time in first exile in Western Europe, Stravinsky drew his inspirations from Russian folklore, Latin and Greek authors and finally French literature. As he was forced into his second exile in the United States, he naturally developed an interest in English literature. Stravinsky first met T.S. Eliot in London for tea in 1956. Initially, “conversation was not easy or flowing, and at times you could almost hear the waiters silently polishing the silverware.” They met on a number of additional occasions, and Stravinsky called Eliot “the most exuberant man I have ever known, but he is one of the purest.” The relationship between Stravinsky and Eliot was not limited to regular encounters; it also inspired two Stravinsky compositions directly linked to Eliot. Anthem, a work for mixed choir emerged when Cambridge University Press asked Stravinsky to contribute a new hymnbook in English. It was Eliot who suggested that “Little Gidding,” part of the “Four Quartets,” would be suitable. Stravinsky also composed Introitus soon after Eliot’s death. It was dedicated to Eliot, and Stravinsky described it as “a small processional rite as the poet would have liked it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Igor Stravinsky: Anthem, “The dove descending breaks the air” (Netherlands Chamber Choir; Reinbert de Leeuw, cond.)