Simon Barere was one of the great pianists of his generation. However, it is possible he is most famous for his sudden death, which occurred in the middle of a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1951.

Today, we’re looking at the shocking story.

Simon Barere’s Childhood

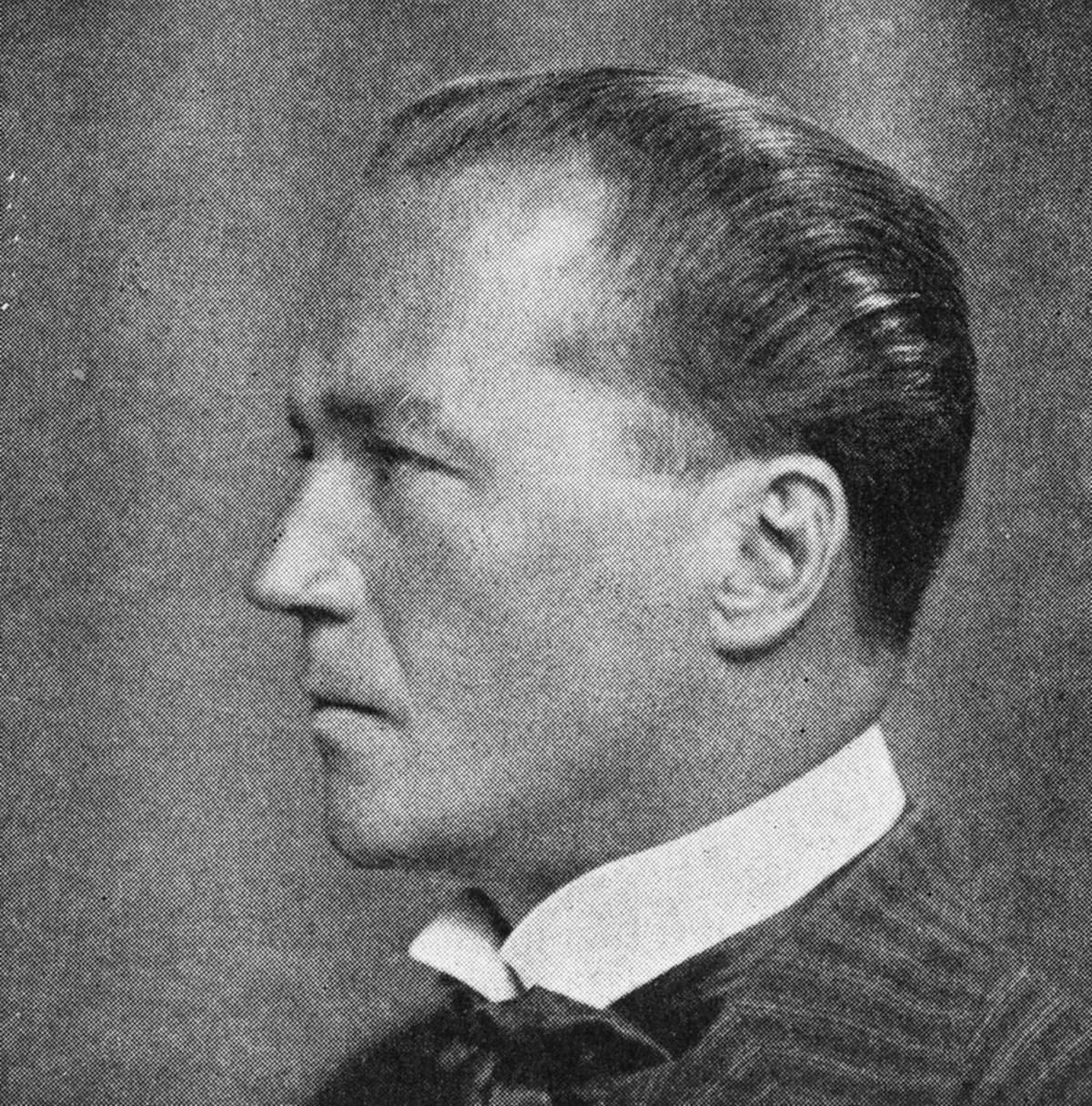

Simon Barere

Simon Barere was born to a Jewish family in 1896 in Odessa in present-day Ukraine. He was the eleventh of thirteen children.

His father died when he was young, and he often played in cafes and movie theaters in Odessa to help support his siblings.

When he was sixteen, his mother died. She had believed in his talent and wanted him to pursue the most rigorous musical education possible. So, to honor her wishes, he moved to St. Petersburg and enrolled in the conservatory there.

While there, he studied under Felix Blumenfeld (a teacher of Horowitz) and Anna Yespiova (a teacher of Prokofiev).

Composer Alexander Glazunov declared him to be an “Anton Rubinstein in one hand and a Liszt in the other.” Glazunov became very fond of Barere and ensured that he was able to stay at the conservatory for a full seven years, which allowed him to avoid being conscripted into the army.

When Barere graduated, he won the Rubinstein Prize and returned to Ukraine to teach at the Kiev Conservatory.

Simon Barere home recording (January 31, 1949)

The Start of a Concert Career – and Escaping the Nazis

In 1920, he married an accomplished piano teacher named Helen Vlashek. The following year, they had a little boy named Boris.

It was very difficult to make a living as a touring pianist in the Soviet Union during this time. Like Horowitz, Barere would often have nothing to show for his performances but a bag of potatoes.

The family eventually fled to Berlin. Unfortunately, the Nazis were coming to power, and more and more restrictions were being placed upon Jewish people.

Rather than performing in great halls as a concerto soloist, he was once again playing in cafes to make ends meet. At one point he was playing between clowns and knife-throwers at the vaudeville. Eventually the family fled again, escaping via Sweden.

A tour through the UK led to recording opportunities. In turn, those recordings led to international recognition, which increased his popularity in America.

Finally, his career was gaining traction. He made his Carnegie Hall debut in 1936 and would appear there annually in the years to come.

In 1939, the Bareres moved to the United States.

Simon Barere Plays Islamey by Balakirev

The Deadly Carnegie Concert

Simon Barere Carnegie Hall concert program

Barere’s last concert was on 2 April 1951 at Carnegie Hall. He appeared playing the Grieg Piano Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy.

Although the Grieg is a fixture of the piano repertoire, it was the first time that Barere had ever been booked to play the work. In addition, his wife Helen and son Boris were sitting proudly in the audience watching.

The concert was sponsored by the American-Scandinavian Foundation, and all of the works on the program were by Scandinavian composers. The concert began with Sibelius’s seventh symphony.

According to New York Times critic Olin Downes, Barere gave no indication that he wasn’t feeling well. He walked “briskly” to the piano bench and waited for the downbeat.

Downes wrote that “Mr. Barere appeared to be in top form” at the beginning of the movement. However, he soon began playing faster and faster, to Downes’s confusion.

At one point, Barere leaned over the keyboard toward the orchestra, as if he was listening intently, then dropped his left arm and fell to the floor.

The orchestra stopped. Someone yelled for a doctor. Barere’s body was lifted “with difficulty” and he was brought backstage to a dressing room.

After discussion, it was decided that the show should continue. The rest of the Grieg concerto was scrapped, and the unnerved musicians played on.

The next work on the program was a song cycle by Swedish composer Ture Rangström called “King Eric’s Songs.” The tenor soloist was Set Svanholm, a Swedish singer who was a favorite at the Metropolitan Opera.

Ture Rangström

Svanholm was shaken up, as he believed that Barere would not survive the attack. Maybe the audience could tell how he was feeling, because they received him “with special enthusiasm,” according to Downes.

Rumors had spread among the crowd that Barere had merely fainted. However, that proved to be an overly optimistic diagnosis.

While Svanholm sang, the dressing room became crowded with three doctors, oxygen tanks, various lifesaving equipment, and later, police.

Barere’s doctor was there; he was no doubt especially nervous about the outcome, as he’d been treating Barere for high blood pressure, and knew how serious his condition could be.

Personnel tried for half an hour to revive him. However, it was no use.

Barere was eventually pronounced dead at the scene. The medical examiner would ultimately declare his cause of death to be “spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage.”

After intermission, the director of the American-Scandinavian Foundation came onstage to address the audience, asking them to stand. He then made the grim announcement that Barrere was dead, and the musicians felt that it would be disrespectful to continue the performance. The crowd was shocked, and performers and audience went home.

Barere’s Legacy

During his lifetime, Barere was often compared to Horowitz, and it’s easy to see why. His recordings reveal a truly electric player.

Here is his final recording session, which occurred days before his death:

Simon Barere – Last Recording Session (March 1951)

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter