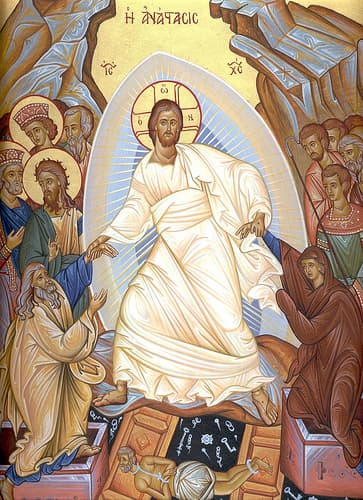

The Christian festival of Easter is sometimes called “Resurrection Sunday.” It is at the heart of Christian belief that Jesus Christ was killed on the cross, but after three days came back to life. I think different branches of Christianity are still arguing whether this is meant to be taken spiritually or refers to a resurrection in body. As a central belief within Christianity, however, resurrection applies to all Christians, as on the Day of Judgment God will judge everybody individually.

According to the Book of Revelation, after people have been judged, they will be sent to either Heaven or Hell. At some point, there was an intermediate stage called purgatory, but I think they have done away with it. With the Easter holiday approaching, I thought it might be fun to find different musical representations of the resurrection.

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber: Mystery (Rosary) Sonata 11 “The Resurrection”

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber: Mystery (Rosary) Sonata 11 “The Resurrection” (Lyriarte)

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Let’s get started with one of the greatest violinists of the 17th century, Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644-1704). He was born towards the end of the Thirty Years War and probably educated in a Jesuit school in Moravia. We know that he took violin lessons, and he soon became famous throughout Europe. A scholar writes, “The Jesuit teachings and the thorough knowledge of the principles of the Catholic faith as well as other subjects taught by the Jesuits, such as rhetoric, dialectics, and mathematics are reflected in Biber’s religious works, especially in his masterpiece collection of “The Mystery Sonatas,” also known as “The Rosary Sonatas.” In the preface to his sonatas, Biber writes, “You will hear my violin, strung with four strings and tuned in fifteen different transformations in various sonatas, preludes, allemandes, courantes, sarabandes, arias, chaconnes, variationes in union with the basso continuo, in pieces, elaborated with much effort, and, inasmuch as was within my power, with great artistry. I included numbers in the sonatas, and if you wish to know the object of these numbers, I shall explain them to you: I arranged them according to the fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary, which you so generously promote.” And as you can hear, the “Sonata 11” refers to the mystery of “The Resurrection.”

Georg Friedrich Telemann: The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus, TWV 6:6

Georg Philipp Telemann

Georg Friedrich Telemann: The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus, TWV 6:6 (Monika Frimmer, soprano; Veronika Winter, soprano; Matthias Koch, counter-tenor; Nico van der Meel, tenor; Klaus Mertens, bass; Rheinische Kantorei; Das Kleine Konzert; Hermann Max, cond.)

Once Georg Friedrich Telemann (1681-1767) had settled in Hamburg, he had some serious marital troubles. His wife was a pathologic gambler, and her debts were larger than Telemann’s annual income. No wonder he composed and published music and poetry at such a staggering rate. In his later years, he focused on theoretical studies and spent much time gardening and cultivating exotic plants. Even though he started to have health problems and failing eyesight, he was still composing in the 1760s. His oratorio The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus dates from 1760, and the libretto was expressly written for Telemann by the “most acclaimed oratorio poet of his time, Karl Wilhelm Ramler.” The poet writes, “I gave a solemn promise to prepare something for Easter at which an old musician will sing his last. Herr Telemann, an elderly man of 78, wants to sing his swansong, and for that, I am to recite the words.” With the text in hand, Telemann went to work and in his recitatives, which narrate the course of the action, Telemann is concerned with natural and clear declamation. Arias are cast into a five-part da capo structure, and the texts of the choruses are free poems on biblical quotations. A contemporary musician writes, “Here Telemann in an exemplary way matched the lyrical and sentiment tone of the poem. It is so moving that when, twice, I sang it through at the piano, both times I had to leave off because of tears.”

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus, H. 777

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus, H. 777 (Lore Binon, soprano; Kieran Carrel, tenor; Andreas Wolf, baritone; Flemish Radio Choir; Il Gardellino; Bart van Reyn, cond.)

C.P. E. Bach

When Telemann died on 25 June 1767, he was succeeded at his Hamburg post by his godson, Johann Sebastian Bach’s second son Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach (1714-1788). C.P.E had been in the services of Frederick the Second of Prussia, but the death of his godfather opened up the way for him to become director of music in Hamburg. Working for the five main churches in Hamburg, C.P.E. left us three great oratorios, including The Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus. You guessed correctly, it is precisely the same text as Telemann had set it. The libretto is not a dramatic narrative, “but a lyrical description of the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, highlighting the feelings aroused by these events, without depicting actual personalities. Although the text is entirely a work of the imagination, it nevertheless contains several paraphrases from the Old and New Testaments.” The work was first performed in 1774, but the composer kept revising the score all the way up to its publication in 1788. C.P.E was very proud of his composition, letting his publisher know that “he considered it to be one of his greatest masterpieces, from which younger composers could learn much.” One such younger composer was no other than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who conducted the work in Vienna. Mozart being Mozart, could not help himself and made several modifications.

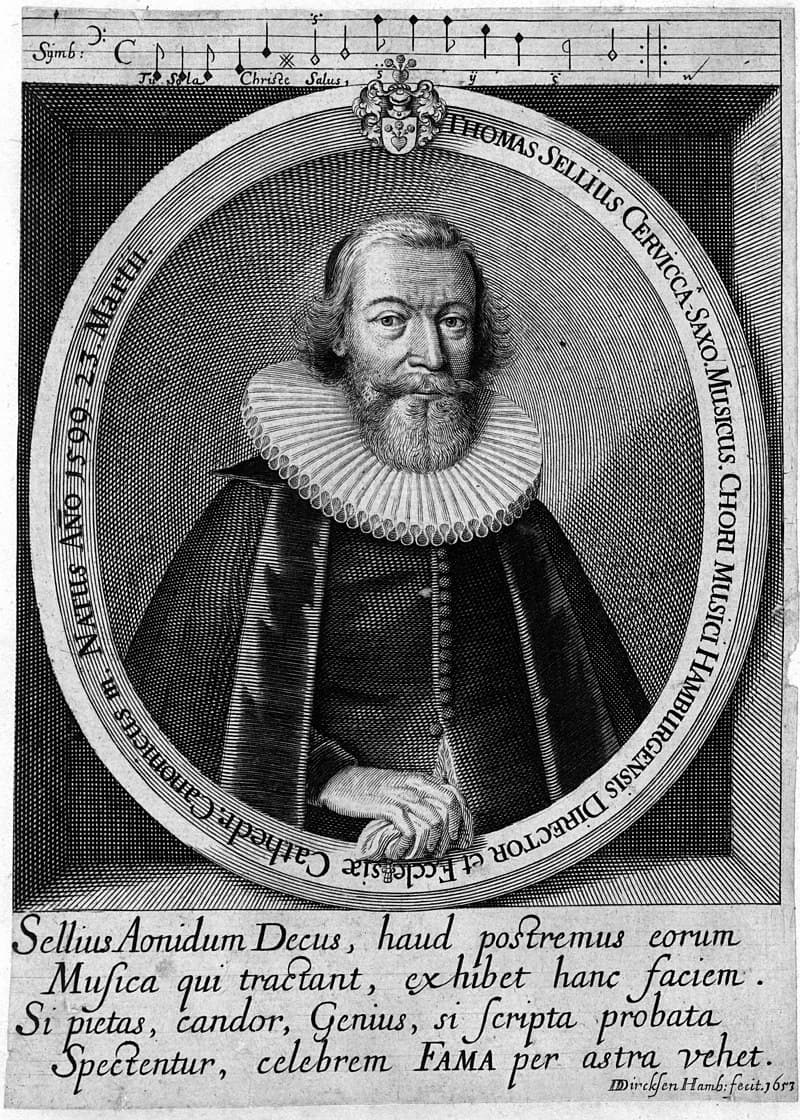

Thomas Selle: The Resurrection of Christ

Thomas Selle

Thomas Selle: The Resurrection of Christ (Monika Mauch, soprano; Manja Stephan, soprano; Beat Duddeck, alto; Mirko Ludwig, tenor; Julian Podger, tenor; Knut Schoch, tenor; Wolf Matthias Friedrich, bass; Weser-Renaissance Bremen; Manfred Cordes, cond.)

Let’s stay in Germany, and specifically, Hamburg, for a little longer and look at The Resurrection of Christ by the seventeenth-century baroque composer Thomas Selle (1599-1663). He was given the vacant position of Kantor at the Johanneum in Hamburg in 1641 “with a unanimous decision and without previous application.” That position was uniquely desirable, as “Hamburg had survived the destruction of the Thirty Years War relatively unscathed and had an increasingly strategic position as a port, and, as a result of foreign trade, also a lively cultural exchange. The city was developing into a prosperous and culturally and politically significant metropolis.” Selle published all his music in Hamburg and taking into account the tastes of the affluent residents of the city, he composed music of the highest quality. Thomas Selle is almost completely unknown today, and a scholar writes, “this runs counter to the significance of his office and the musical conceptual influence he had in the field of dialogues and histories on later generations.”

Charles Villiers Stanford: The Resurrection, Op. 5

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock

Charles Villiers Stanford: The Resurrection, Op. 5 (Robert Murray, tenor; The Bach Choir; Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; David Hill cond.)

The German poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) is probably best known for his epic poem “The Messiah,” which is considered his major contribution to German literature. A scholar writes, “by enrichment of poetic vocabulary and attention to prosody he did great service to the poets who immediately followed him. In freeing German poetry from its exclusive interest in Alexandrine verse, he became the founder of a new era in German literature, so that Schiller and Goethe were artistically indebted to him.” Kopstock published his “Resurrection Ode” in 1758 and the text was quickly paired with a melody by Martin Luther. The opening two verses read:

Arise, yes, you will arise from the dead,

My dust, after a short rest!

Eternal life!

Will be given you by Him who called you.

To bloom again are you sown.

The lord of the harvest goes

And gathers the sheaves,

Us who have died.

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852–1924) discovered Klopstock’s “Resurrection Ode” during his student day in Leipzig. Studying under Carl Reinecke he decided to set the Kopstock text in a short choral work titled The Resurrection, Op. 5. Reinecke was delighted and advised Stanford to have the work performed in England. Stanford gave its first performance on 21 March 1875 sung in its English version. He revised it for a supposed second performance in Cambridge or London, but the work has since been almost entirely neglected.

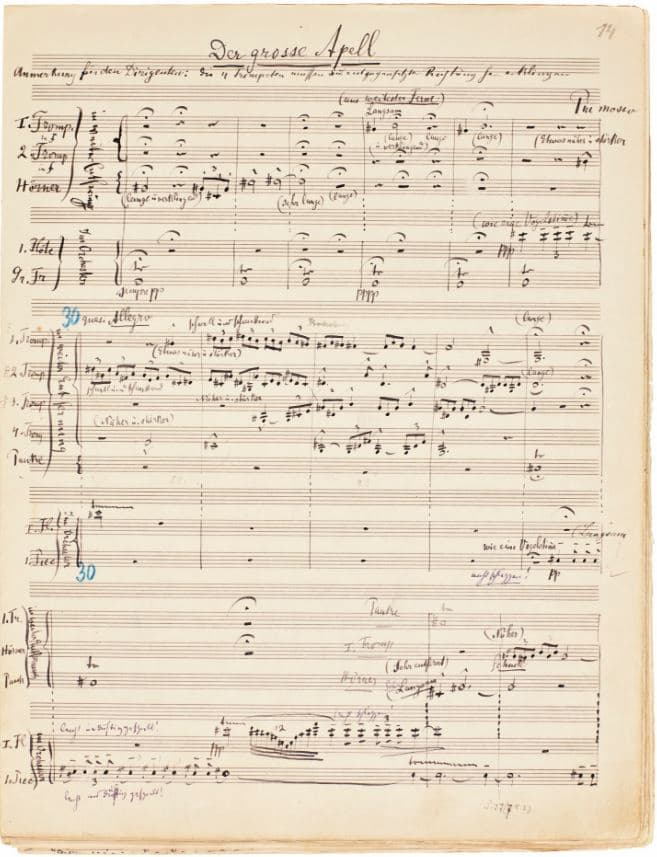

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection”

An anecdote tells that when Gustav Mahler heard the Klopstock “Resurrection Ode” at the funeral of Hans von Bülow in 1894, he found the inspiration for the final movement of his Second Symphony, also known as the “Resurrection Symphony.” Mahler incorporated the hymn with extra verses that he wrote, in the concluding movement. The final verse reads:

Arise, yes, you will arise from the dead,

My heart, in an instant!

What you have conquered

Will bear you to God.

Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 “Resurrection”

The concluding movement is introduced by offstage horns and trumpets that gradually draw nearer, and birdcalls in the flute and piccolo hint at the arrival in the heavenly sphere. Silence descends once more, and quietly the chorus begins to intone the hymn of resurrection. Each of the first two verses is followed by an instrumental interlude.

The third verse is sung by an alto and soprano duet, and precedes a further proclamation by the chorus. The final duet leads into the triumphant sounding of the resurrection chorale, and the instrumental coda—having successfully transformed the opening C minor tonality into a brilliant E-flat major—concludes one of the most moving works in the symphonic repertory. Mahler himself remarked, “The increasing tension, working up to the final climax, is so tremendous that I don’t know myself how I ever came to write it.”

Albert Roussel: Resurrection, Op. 4

Albert Roussel, 1913

Albert Roussel: Resurrection, Op. 4 (Toulouse Capitol Orchestra; Michel Plasson, cond.)

When I first started listening to Albert Roussel’s symphonic prelude Résurrection I was convinced that it portrayed the resurrection of Christ. The menacing opening with brass and timpani builds in emotion towards an apotheosis that fades away during a final resolution. To my surprise, it is not based on the biblical story at all, but on the last novel written by Leo Tolstoy. Resurrection tells the story of a nobleman who sexually assaults the goddaughter of his Aunt. When she gets pregnant, she is thrown out by the Aunt and ends up working as a prostitute. Ten years later, the man sits on a jury, which sentences the girl to prison in Siberia for murder. “The book narrates his attempts to atone for his sins, while focusing on his personal mental and moral struggle.” He visits her in prison and becomes part of the prison community. He gives up all his property and follows the girl into exile, planning on marrying her. However, on their long journey into Siberia, she falls in love with another man, and he gives his blessing while still choosing to live as part of the penal community, seeking redemption. That’s an entirely different resurrection story for sure, and it led to Tolstoy’s ex-communication by the Holy Synod from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901.

Peter Maxwell Davies: Resurrection, “Song of the New Resurrection”

Peter Maxwell Davies

Peter Maxwell Davies: Resurrection, “Song of the New Resurrection” (Mary Carewe, soprano; Della Jones, mezzo-soprano; Neil Jenkins, tenor; Christopher Robson, counter-tenor; Martyn Hill, tenor; Gerald Finley, baritone; Jonathan Best, bass; Lesley-Jane Rogers, soprano; Deborah Miles-Johnson, alto; John Bowley, tenor; Mark Rowlinson, bass; Blaze; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Maxwell Davies, cond.)

In Resurrection, an opera by the English composer Peter Maxwell Davies, we are thrust into an apocalyptic vision of an elaborate operation to transform a patient. It has been called “one of the fiercest works of social criticism ever to come from the pen of a classical composer.” The opera’s hero is a dummy who never once sings or moves. The child is a nonconformist who must be made to fit into a puritanical society, and four surgeons devise an elaborate series of operations to remedy the supposed defects. The first dissects his brain, seeking to rectify his moral and intellectual faults; a second examines his heart, correcting his emotional and religious failings, whilst a third adjusts his ‘sexual proclivities’ by removing his testicles. But the surgery goes awry, and the patient is resurrected as the Antichrist, announcing the impending apocalypse. That’s a pretty heavy-duty story, so the composer “handles the material with an irreverent, comic touch.” The music features happily colliding historical styles, vocal soloists, dancers, a Rock Band, and a Salvation Army Band. In all, there are 23 roles requiring seven singers for this 21st century exploration of the Resurrection.

Krzysztof Penderecki: Piano Concerto “Resurrection”

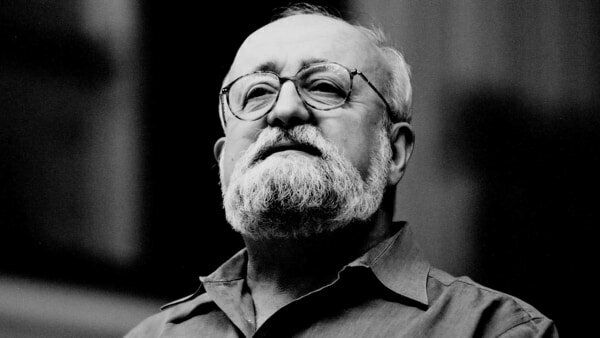

The concept of “Resurrection” is subject to varying interpretations so let me conclude this blog with Krzysztof Penderecki’s Piano Concerto “Resurrection.”

Krzysztof Penderecki

The composer explains, “I set about writing the Concerto in June and was halfway through it after a few months; it was something like a capriccio. But after 11 September 2001, the conception changed completely. I decided to write a darker, more serious work. I cut out some of the material, went back to a certain point in the structure, and added a chorale, which first appears roughly at one-third of the music and reappears twice, the last time at the end of the Concerto. It is then played rather slow, allegro moderato, and after a few faster strokes the Concerto ends.” In this work, I hear a collection of loosely related fragments sounded in neo-expressiveness. Ten movements are played without a pause, and the “Resurrection” is sounded in the chorale that emerges “at full strength during the climatic stages.” Audiences and critics didn’t like the work at all, and the composer revised it in 2007. A scholar writes, “Extensive political-social associations are readily found in Penderecki’s works. These associations in content are not merely an abstract concept, but also in their instrumental tonal colouring and dramatic sounds emotionally comprehensible for listeners.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter