Beethoven’s orchestra in 1804, when he conducted the first performance of his Symphony No. 3, and Mahler’s orchestra a century later were very different. Developments in string technology, in brass and woodwind instrument construction, and in the very sound and balance of the orchestra had all changed. Mahler’s orchestra had about 3 times the number of strings that Beethoven’s had, but the wind sections did not have a comparable increase. The brass was now not only better (due to the move away from the natural trumpet to the valve trumpet) but also louder. The balance of sound was off, but then the very size of the concert halls had increased. It wasn’t possible to return to Beethoven’s string/wind proportions, so something had to be done to bring things back into measure.

Christian Hornemann: Ludwig von Beethoven, 1803

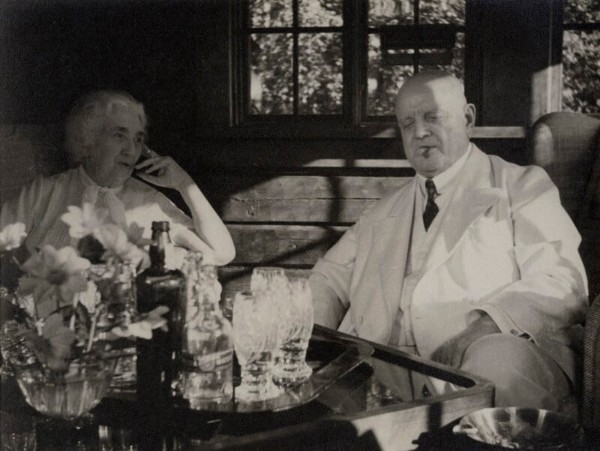

Moritz Nähr: Gustav Mahler, 1907

Beethoven’s first two symphonies were very much in the Haydn/Mozart tradition. Beethoven dumped Haydn’s trombones and only used 2 horns, but otherwise was much the same. The duration was about 30 minutes, and there were four movements. When Beethoven got to Symphony No. 3, though, the idea of the epic crept in. Now the work is 45 minutes to an hour long (depending on your tempos); the work was dedicated to ‘the memory of a great man’ and sets out to be a remarkably individual work, unlike any of the symphonies that preceded it – be it by Beethoven or by his predecessors.

The choice of key (E flat major) immediately casts the work as positive. The subtitle ‘sinfonia eroica’ shows Beethoven’s intentions, and the use of his earlier music from The Creatures of Prometheus gives us a narrative—this is not music to entertain but to uplift. This is a social message for the new bourgeoisie, not an uplifting sacred message.

Throughout the work, Beethoven breaks the rules, starting with the first theme. It’s not a theme as much as an arpeggiated chord. This is the birth of the Beethoven, for whom rhythm overrides melody.

When Mahler sat down to make his ‘Retuschen’ (retouchings), he was not seeking to modernize Beethoven but to improve the works’ intelligibility and clarity. The first step Mahler took was to ‘improve their legibility’, which consisted of not only making the annotations such as keys and changes better but also of analysing where Beethoven had to write around the limitations of the instruments of his day. Horns and trumpets might go silent because the work was going into keys where they didn’t sound well, melodies might change octaves because the string or wind instruments sounded too shrill at the higher pitch level. The wind sound might get buried under an instrumental tutti. The balance between relative and absolute loudness had to be maintained: a fortissimo in the brass is very different than a fortissimo in the woodwinds, and the brass must be scaled back so they don’t bury the winds. That was step one.

Step two occurred once the music was on the stands. With the reality of his orchestra’s sound with Beethoven’s music, Mahler could now hear where the winds needed to be doubled, where voices needed to be added, and where melodies needed to change octave. All of this was in the service of making the melodic material come through more clearly. Mahler did conducted 11 performances of his Beethoven’s Eroica.

All of this was not unusual for the conductors of the day, but, at times, it was felt that Mahler went too far, particularly in his retouchings of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony.

Listen, for example, to the difference between Leonard Bernstein’s Third and Mahler’s retouched version: Mahler’s brass is scaled back, the strings are more restrained, and so on.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” (re-orchestrated by G. Mahler) – I. Allegro con brio (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” – I. Allegro con brio (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

In the second movement, the funeral march, the dark and slow march is contrasted by a brighter funeral ode. Bernstein’s performance is more demonstrative, but is that a good thing?

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” (re-orchestrated by G. Mahler) – II. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” – II. Marcia funebre: Adagio assai (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

The Scherzo, which was Beethoven’s innovative addition to the symphony starting with his Symphony No. 2, replacing the earlier Minuet, maintains the contrasting Trio section that was always part of a Minuet movement.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” (re-orchestrated by G. Mahler) – III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” – III. Scherzo: Allegro vivace (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

The Finale was where Mahler was particularly careful. For him, the key was not to take the tempo too quickly. Care had to be taken that the various themes have the time to sing out on their own. It’s a delicate balance. Listen, for example, to how these different performances start. They both take 11 seconds to get to the cadence, but what a difference in feeling – the Bernstein feels almost as though it’s falling down a hill!

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” (re-orchestrated by G. Mahler) – IV. Finale: Allegro molto (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Michael Francis, cond.)

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55, “Eroica” – IV. Finale: Allegro molto (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Bernstein, cond.)

You’ll hear more and more as you get familiar with the work before Mahler made his adjustments. Richard Wagner, who also made his own Beethoven versions, notes that Beethoven’s ‘Sinfonia Eroica remains both a miracle of design and a miracle of orchestration. However, Beethoven here requires a style of performance that no orchestra to this day has managed to deliver…’ and then goes on to say, ‘These works lack clarity in performance because achieving such clarity was no longer inherent in the orchestral organism that Haydn and Mozart had known. It can, in fact, only be achieved by musical brilliance on the part of the individual instrumentalists and their conductor…’.

Richard Wagner, 1861

If Beethoven, as always, was decades ahead of his contemporaries, it was composers and conductors such as Wagner and, more importantly, Mahler who tried to make that delicate balance between Beethoven’s unachieved desires and modern orchestras. Mahler’s goal was a correct performance, but one that might not be considered beautiful by the standards of his day. Mahler’s retouchings were intended to bring out Beethoven’s unrealized desires.

In a magnificent turnabout, by the 1970s, Maher’s work was viewed as ‘unjustifiable interference’ as the historically informed practices did what Mahler couldn’t: reduce the size of the strings and return to the valve-less natural trumpets and horns (and their attendant problems). We now turn back to Mahler to see that his alternative readings, his retouchings, had a point and an audience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter